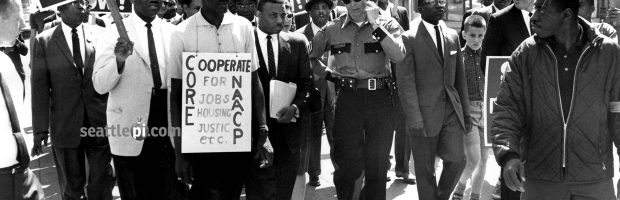

On this final Theme Thursday in Black History Month, we want to focus on revolutionary texts to help you #staywoke. Some of us have had that experience of awakening to what’s going on in the world. Whether it’s from watching a movie documenting the civil rights movement or reading about the life of Malcolm X, there comes a point in time when you might “wake up” and start reading and researching about the issues of institutional and systemic racism. These seven classic revolutionary reads listed here will give you a head start on that path.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley

The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley

Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community

Die, Nigger, Die!: A Political Autobiography

Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson

By the way, in case you weren’t sure, Merriam-Webster offers the following definition of woke. “Stay woke became a watch word in parts of the black community for those who were self-aware, questioning the dominant paradigm and striving for something better. But stay woke and woke became part of a wider discussion in 2014, immediately following the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The word woke became entwined with the Black Lives Matter movement; instead of just being a word that signaled awareness of injustice or racial tension, it became a word of action. Activists were woke and called on others to stay woke. Like many other terms from black culture that have been taken into the mainstream, woke is gaining broader uses. It’s now seeing use as an adjective to refer to places where woke people commune: woke Twitter has very recently taken off as the shorthand for describing social-media activists.”