ŽIŽEK GOADS AND PRODS, by Slovoj Žižek, posted a fascinating essay on Hamlet: “When God Cries: Hamlet and the Art of World-Shattering change” earlier this year, using John Updike’s prequel to Shakespeare’s famous tragedy to further his argument.

“There are thus good arguments for the premise of John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius that Hamlet’s father is the truly evil person in the play, and that his injunction to Hamlet is an obscenity. Updike’s novel is a prequel to Shakespeare’s play: Gertrude and Claudius are engaged in an adulterous affair (Shakespeare is ambiguous on this point), and this affair is presented as passionate true love. Gertrude is a sensual, somewhat neglected wife, Claudius a rather dashing fellow, and old Hamlet an unpleasant combination of brutal Viking raider and coldly ambitious politician. Claudius has to kill the old Hamlet because he learns that the old king plans to kill them both (and he does it without Gertrude’s knowledge or encouragement). Claudius turns out to be a good, generous king; he lives and reigns happily with Gertrude, and everything runs smoothly until Hamlet returns from Wittenberg and throws everything out of joint. Whatever we imagine as the (fictional) reality of Hamlet, Gertrude is the only kindhearted and basically honest person in the play.”

“There are thus good arguments for the premise of John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius that Hamlet’s father is the truly evil person in the play, and that his injunction to Hamlet is an obscenity. Updike’s novel is a prequel to Shakespeare’s play: Gertrude and Claudius are engaged in an adulterous affair (Shakespeare is ambiguous on this point), and this affair is presented as passionate true love. Gertrude is a sensual, somewhat neglected wife, Claudius a rather dashing fellow, and old Hamlet an unpleasant combination of brutal Viking raider and coldly ambitious politician. Claudius has to kill the old Hamlet because he learns that the old king plans to kill them both (and he does it without Gertrude’s knowledge or encouragement). Claudius turns out to be a good, generous king; he lives and reigns happily with Gertrude, and everything runs smoothly until Hamlet returns from Wittenberg and throws everything out of joint. Whatever we imagine as the (fictional) reality of Hamlet, Gertrude is the only kindhearted and basically honest person in the play.”

Nigel Beale, of The Biblio File podcast, posted an

Nigel Beale, of The Biblio File podcast, posted an  For this entry we need to thank writer

For this entry we need to thank writer

Coming in at #2 was Donald Sassoon’s Becoming Mona Lisa, which traces the path to superstardom of Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous subject/painting—a study that Brown said “suggests that, contrary to popular and scholarly belief, posterity is a peculiarly fickle thing.”

Coming in at #2 was Donald Sassoon’s Becoming Mona Lisa, which traces the path to superstardom of Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous subject/painting—a study that Brown said “suggests that, contrary to popular and scholarly belief, posterity is a peculiarly fickle thing.”

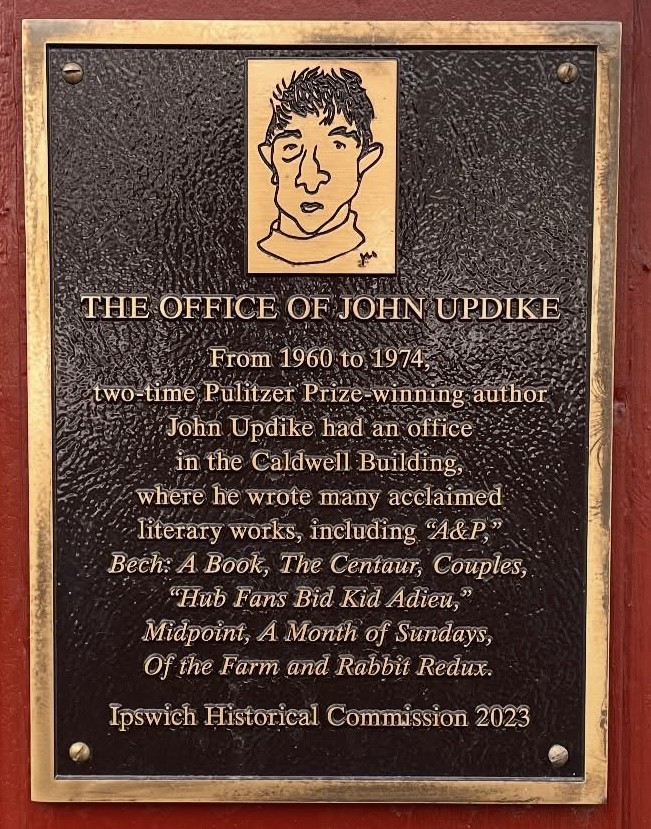

It’s not exactly a doorstop, but at 186 pages, the Vol. 11 No. 1 (Winter 2024) issue of The John Updike Review is the largest to date. From the striking cover—a full-color photo of Updike with his father in a candid moment—to end pages that feature opportunities for writers and scholars, this issue has a lot to offer.

It’s not exactly a doorstop, but at 186 pages, the Vol. 11 No. 1 (Winter 2024) issue of The John Updike Review is the largest to date. From the striking cover—a full-color photo of Updike with his father in a candid moment—to end pages that feature opportunities for writers and scholars, this issue has a lot to offer.

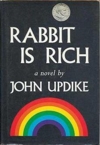

“The third installment of John Updike’s ‘Rabbit’ series finds Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom finally comfortable—or at least financially secure—amid the tumultuous backdrop of 1979’s oil crisis and stagflation. ‘How can you respect the world when you see it’s being run by a bunch of kids turned old?’ the narrator observes, capturing the novel’s eerie contemporary resonance: interest rates and real-estate climbing skyward—and staying there—and a gnawing certainty that the next generation won’t have it quite so good. Updike’s prose transforms the mundane rhythms of middle-class life into something approaching poetry as he excavates middle-class anxiety and success. Rabbit’s car dealership is printing money thanks to the Japanese vehicles he sells, even as his own prejudices and racial anxieties bubble beneath the surface. His son Nelson is adrift, the world seems to be coming apart at the seams and Rabbit’s own biases reflect the tensions of a changing America. The novel won Updike both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for its devastating precision in capturing what it means to ‘make it’ while watching the ladder get pulled up behind you.”

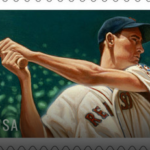

“The third installment of John Updike’s ‘Rabbit’ series finds Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom finally comfortable—or at least financially secure—amid the tumultuous backdrop of 1979’s oil crisis and stagflation. ‘How can you respect the world when you see it’s being run by a bunch of kids turned old?’ the narrator observes, capturing the novel’s eerie contemporary resonance: interest rates and real-estate climbing skyward—and staying there—and a gnawing certainty that the next generation won’t have it quite so good. Updike’s prose transforms the mundane rhythms of middle-class life into something approaching poetry as he excavates middle-class anxiety and success. Rabbit’s car dealership is printing money thanks to the Japanese vehicles he sells, even as his own prejudices and racial anxieties bubble beneath the surface. His son Nelson is adrift, the world seems to be coming apart at the seams and Rabbit’s own biases reflect the tensions of a changing America. The novel won Updike both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for its devastating precision in capturing what it means to ‘make it’ while watching the ladder get pulled up behind you.” Thomas wrote, “On a dreary Wednesday in September, 1960, John Updike, ‘falling in love, away from marriage,’ took a taxi to see his paramour. But, he later wrote, she didn’t answer his knock, and so he went to a ballgame at Fenway Park for his last chance to see the Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, who was about to retire. For a few dollars, he got a seat behind third base.

Thomas wrote, “On a dreary Wednesday in September, 1960, John Updike, ‘falling in love, away from marriage,’ took a taxi to see his paramour. But, he later wrote, she didn’t answer his knock, and so he went to a ballgame at Fenway Park for his last chance to see the Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, who was about to retire. For a few dollars, he got a seat behind third base.