Dorothy Huber, who lived next door to The John Updike Childhood Home and was a wonderful neighbor during the 10 years that the society owned the property, died peacefully at age 92 on April 28, 2024.

Dorothy was a dynamic individual who worked as an office manager and accountant until she was 85. She also devoted much of her time to charity work, including service as a past president of the Reading Soroptimist International professional business women’s organization and as a member of the Berks County Prison Society where, according to her obituary, she “brought the Word of God to incarcerated individuals. Her impact was amazing, lives were changed, and the success stories made her smile; she saw this as a highlight in her life’s work.”

Dorothy was a dynamic individual who worked as an office manager and accountant until she was 85. She also devoted much of her time to charity work, including service as a past president of the Reading Soroptimist International professional business women’s organization and as a member of the Berks County Prison Society where, according to her obituary, she “brought the Word of God to incarcerated individuals. Her impact was amazing, lives were changed, and the success stories made her smile; she saw this as a highlight in her life’s work.”

Dorothy also kept an eye on the Updike property and looked forward to visits from society president James Plath when he traveled from Illinois to Shillington to work on the house. The feeling was mutual. “Just about every trip included an hour or two at Dorothy’s, talking about this and that,” Plath said. “She was also very interested in Updike and the progress that we were making on the museum.”

Updike’s Shillington contact, Dave Silcox, was even closer, regularly checking on Dorothy and bringing dinners on special occasions. It was during one of those visits with Silcox that Dorothy asked if the society would have any interest in buying an elaborate carved sideboard that came out of Clint Shilling’s house. The answer was yes.

Mrs. Updike paid Shilling to give her son art lessons when he was only five years old, so the Updike connection was a great interest. It turned out that Dorothy and Shilling were good friends, and she was told that she could take what she wanted after he passed away. She took the sideboard but also rescued a lot of Shilling’s paint scoops and brushes and some of the artwork as well.

The society bought the sideboard and many of the Shilling items from her, and they now are on display in the museum. The sideboard especially is a unique item that young John Updike would have seen when he crossed the street to take lessons from Shilling. Sometimes Shilling conducted lessons on the Updikes’ side porch, while other times young Johnny went to Shilling’s house. The sideboard meant a lot to Huber, but it meant even more to her that people would continue to enjoy it in the museum next door to her house.

Always smiling and cheerful, Dorothy had what sounds like a cliché: a perpetual twinkle in her eyes. She loved life, loved people, and loved helping people. She was a good neighbor and friend who will be deeply missed. The society offers its heartfelt condolences to Dorothy’s son, daughter, and grandchildren.

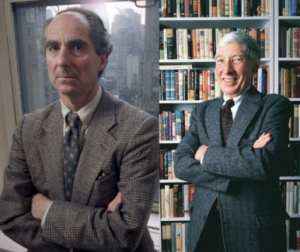

On the American Literature public Facebook group, Milan Milan Stankovic posted a consideration/comparison of two “Great American Writers” whose works offer “profound insights into American society, culture, and individual psychological and individual psychological complexities”: John Updike and Philip Roth.

On the American Literature public Facebook group, Milan Milan Stankovic posted a consideration/comparison of two “Great American Writers” whose works offer “profound insights into American society, culture, and individual psychological and individual psychological complexities”: John Updike and Philip Roth.

Edwin Woodruff, who was given a copy of Gertrude and Claudius by a cast member when he directed the play for community theater, wrote in a Patheos column that while he found Updike’s sequel to Shakespeare’s Hamlet “a bit offputting” in the beginning, with a style that “seemed stilted and awkward and the analysis of everyone’s motivations and thoughts rather labored and obvious. But it grew on me as it went on.

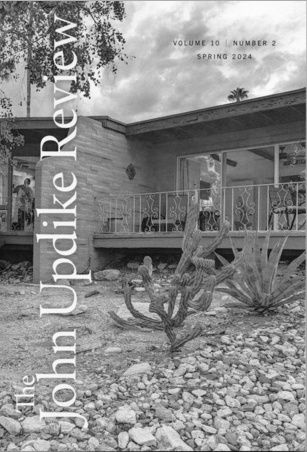

Edwin Woodruff, who was given a copy of Gertrude and Claudius by a cast member when he directed the play for community theater, wrote in a Patheos column that while he found Updike’s sequel to Shakespeare’s Hamlet “a bit offputting” in the beginning, with a style that “seemed stilted and awkward and the analysis of everyone’s motivations and thoughts rather labored and obvious. But it grew on me as it went on. Volume 10, Number 2 (Spring 2024) of The John Updike Review was recently published, and Updike society members have been quick to comment on the stunning cover: a photograph of the Tucson casitas that John and Martha Updike owned and lived in each spring between 2004-2008. The photo was taken by the journal’s editor, James Schiff, when attendees at the 7th Biennial John Updike Society Conference in Tucson had the opportunity to tour the casitas.

Volume 10, Number 2 (Spring 2024) of The John Updike Review was recently published, and Updike society members have been quick to comment on the stunning cover: a photograph of the Tucson casitas that John and Martha Updike owned and lived in each spring between 2004-2008. The photo was taken by the journal’s editor, James Schiff, when attendees at the 7th Biennial John Updike Society Conference in Tucson had the opportunity to tour the casitas. Dr. Carla Alexandra Ferreira, a Brazilian scholar whose YouTube channel is “Carla Ferreira: Literary Dialogues,” has featured brief discussions of two John Updike novels:

Dr. Carla Alexandra Ferreira, a Brazilian scholar whose YouTube channel is “Carla Ferreira: Literary Dialogues,” has featured brief discussions of two John Updike novels:  This National Windows Day (that’s a thing?), renowned photographer Jill Krementz shared some of the photos she took of

This National Windows Day (that’s a thing?), renowned photographer Jill Krementz shared some of the photos she took of

Sue Norton, Lecturer of English in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Technological University Dublin, Ireland, has accepted an invitation to join The John Updike Society Board of Directors. Her appointment is effective immediately.

Sue Norton, Lecturer of English in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Technological University Dublin, Ireland, has accepted an invitation to join The John Updike Society Board of Directors. Her appointment is effective immediately. “We float above events, seeing them from the perspective of different characters, sometimes switching viewpoint over the space of a paragraph,” Jones wrote. “Rabbit, Run expresses a desire to transcend ordinary life, while also suggesting—in the manner of Ecclesiastes—that the only meaningful escape available to us lies in ordinary things. In the end, Rabbit, Run does not promise any kind of silly nirvana, but it does suggest a more liberating and interesting way of looking at the non-nirvana in which we spend our days.”

“We float above events, seeing them from the perspective of different characters, sometimes switching viewpoint over the space of a paragraph,” Jones wrote. “Rabbit, Run expresses a desire to transcend ordinary life, while also suggesting—in the manner of Ecclesiastes—that the only meaningful escape available to us lies in ordinary things. In the end, Rabbit, Run does not promise any kind of silly nirvana, but it does suggest a more liberating and interesting way of looking at the non-nirvana in which we spend our days.” On May 3, 2024, the “Novelist Spotlight: Interviews and insights with published fiction writers” blog looked in the rear-view mirror to discuss a writer who, according to host and novelist Mike Consol, wrote more beautifully in English than anyone else.

On May 3, 2024, the “Novelist Spotlight: Interviews and insights with published fiction writers” blog looked in the rear-view mirror to discuss a writer who, according to host and novelist Mike Consol, wrote more beautifully in English than anyone else. Dorothy was a dynamic individual who worked as an office manager and accountant until she was 85. She also devoted much of her time to charity work, including service as a past president of the Reading Soroptimist International professional business women’s organization and as a member of the Berks County Prison Society where, according to her

Dorothy was a dynamic individual who worked as an office manager and accountant until she was 85. She also devoted much of her time to charity work, including service as a past president of the Reading Soroptimist International professional business women’s organization and as a member of the Berks County Prison Society where, according to her