As part of their feminist classics series which looks at influential books, The Conversation featured an article on “Sex, zips and feminism: Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying has a joyful abandon rarely found in today’s sad girl novels” in which John Updike was quoted.

As part of their feminist classics series which looks at influential books, The Conversation featured an article on “Sex, zips and feminism: Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying has a joyful abandon rarely found in today’s sad girl novels” in which John Updike was quoted.

“Interestingly though, another male writer, John Updike, helped Jong’s rise up the bestseller list. Even so, his compliments can read as backhanded as Goodlove’s:

It has class and sass, brightness and bite. Containing all the cracked eggs of the feminist litany, her soufflé rises with a poet’s afflatus. She sprinkles on the four-letter words as if women had invented them; her cheerful sexual frankness brings a new flavor to female prose.

“Updike favourably links Jong with great male writers J.D. Salinger and Philip Roth, while carefully distinguishing her from the more disagreeable women’s liberationists:

Fear of Flying not only stands as a notably luxuriant and glowing bloom in the sometimes thistly garden of ‘raised’ feminine consciousness but belongs to, and hilariously extends, the tradition of Catcher in the Rye and Portnoy’s Complaint.

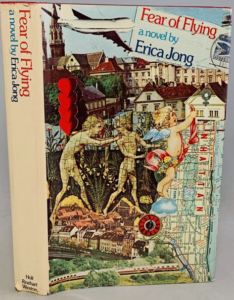

“Pull quotes from Updike’s review featured on the novel’s second edition (the one I have been reading), along with a new cover: a luscious 70s serif typeface in black and orange on a yellow background that blatantly copies the 1969 cover of Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint.”

Mid-way through his essay, Sundahl remarked, “Of course there’s religion and then there’s religion and there are books and there are dirty books. . . which raises the question: Can one write about life, even life’s carnality and concupiscence, while maintaining Christian aspects?” He also, of course, attempted to answer his own question in a classical, meandering way, prompted by the last words (“the children”) of Updike’s novel, In the Beauty of the Lilies.

Mid-way through his essay, Sundahl remarked, “Of course there’s religion and then there’s religion and there are books and there are dirty books. . . which raises the question: Can one write about life, even life’s carnality and concupiscence, while maintaining Christian aspects?” He also, of course, attempted to answer his own question in a classical, meandering way, prompted by the last words (“the children”) of Updike’s novel, In the Beauty of the Lilies.