The Great Gatsby is often cited as a contender for that elusive (and purely speculative) title of “Great American Novel,” and editors of The Atlantic used that novel as a starting point for reconsidering what that term actually means in order to construct their own list of “The Great American Novels.”

The editors decided to define “American” as having been first published in the U.S., they narrowed the field to the past 100 years (“a period that began as literary modernism was cresting”), and they approached “scholars, critics, and novelists, both at The Atlantic and outside it” asking for suggestions. Their aim: “the very best—novels that say something intriguing about the world and do it distinctively, in intentional, artful prose.” That resulted in a list of 136 books, and if you break that list down by decades it looks like this: 7 from the ’20s, 9 from the ’30s, 7 from the ’40s, 13 from the ’50s, 15 from the ’60s, 19 from the ’70s, 12 from the ’80s, 16 from the ’90s, 14 from the ’00s, 21 from the ’10s, and 3 from the current young decade—reflecting, perhaps, a fairly large familiarity factor based on the ages of those who weighed in.

The editors decided to define “American” as having been first published in the U.S., they narrowed the field to the past 100 years (“a period that began as literary modernism was cresting”), and they approached “scholars, critics, and novelists, both at The Atlantic and outside it” asking for suggestions. Their aim: “the very best—novels that say something intriguing about the world and do it distinctively, in intentional, artful prose.” That resulted in a list of 136 books, and if you break that list down by decades it looks like this: 7 from the ’20s, 9 from the ’30s, 7 from the ’40s, 13 from the ’50s, 15 from the ’60s, 19 from the ’70s, 12 from the ’80s, 16 from the ’90s, 14 from the ’00s, 21 from the ’10s, and 3 from the current young decade—reflecting, perhaps, a fairly large familiarity factor based on the ages of those who weighed in.

“This list includes 45 debut novels, nine winners of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction [Updike’s two winners from the Rabbit series didn’t make the cut], and three children’s books. . . . At least 60 have been banned by schools or libraries. Together, they represent the best of what novels can do: challenge us, delight us, pull us in and then release us, a little smarter and a little more alive than we were before.”

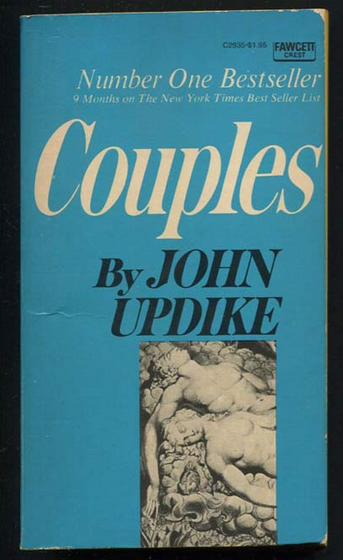

Of Couples, one of the editors writes, “Couples caused a scandal when it was first published, but it was easy for Updike to weather. Having written a novel about suburban adultery before such novels were commonplace, he anticipated some outrage. No matter: The fainting-couch wailing only made him more famous. But what did matter to Updike were the friendships that he nuked. The book was a thinly disguised ethnography of his bored and prosperous social set in Ipswich, Massachusetts, which was torn between rigid WASPy mores and the enticements of the sexual revolution. Not all of his friends forgave him. How could they? It’s one thing to have your dinner-party pretensions and proto-polyamory exposed on the page. It’s quite another to have them rendered in precise lyrical prose by an all-time great American stylist. Nearly 60 years on, their loss is still our gain.”