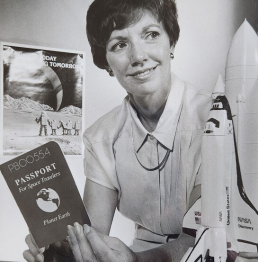

A remarkable Berks County woman died on May 16, 2023. Ellen Lou Gallagher (Brownmiller) was a beloved teacher who touched many lives, but she was also a student, artist, musician, playwright, quilter, and “almost an astronaut when she was a Pennsylvania finalist for the Teacher in Space program in 1985,” according to her obituary.

Her son, Drew Gallagher, told The John Updike Society that Ellen had “three organizations that were very dear to her and one was the Updike Childhood Home.” In lieu of flowers, the family requested that donations be made to those three organizations: The Reading Symphony, The John Updike Childhood Home, or The Kurt Vonnegut Museum. “Or simply read a favorite book or listen to a show tune in her honor. Try to remember when love was an ember about to billow. When everything was beautiful and nothing hurt. And so it goes.”

Born in West Reading on July 1, 1941, Gallagher graduated from Millersville State with a degree in education and added a Master’s degree from Temple University years later. “Ultimately she landed at Lorane Elementary School in Exeter as a fifth grade teacher. Her students will remember the annual incubation projects, waiting for the chicks to hatch in the classroom, and they will not forget learning what a million something looked like when they collected that many aluminum can pull tabs over many more school years than anticipated. There was a large ceremony at Lorane to commemorate the millionth pull tab and photos were taken and published in The Reading Eagle [where her late husband, Charles Gallagher, was longtime editor] before the tabs were recycled.”

Gallagher spent summer 1981 teaching children on the island of Majuro in the Marshall Islands and was an inspiration for a character in the young adult novel Me and Marvin Gardens, written by one of her former students, A.S. King.

Perhaps most remarkably, when she retired she had two goals: “learn to quilt and to play the violin. She was successful at both. As a member of the Reading Philharmonic Orchestra, she played the violin until she was unable and then became the narrator for their concerts up until her death.”

The John Updike Society is touched that a person who loomed so large in so many lives thought enough of John Updike and our little childhood home museum to name us as a donation beneficiary. Even in death, she continues to make a difference and set an example. Our deepest sympathies go out to her sons Drew and Thomas, her daughter Julie Stern, and their families.