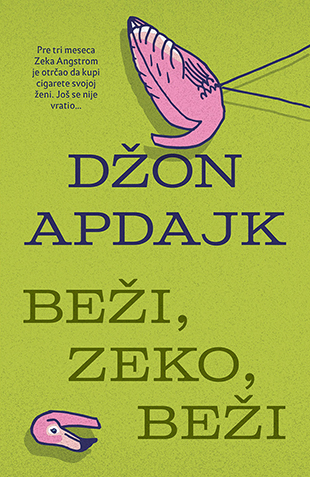

Laguna, the largest publishing house in Serbia, announced the release of a second edition of John Updike’s Rabbit, Run in June 2018—39 years after the first edition of the novel was published in Serbian.

Laguna, the largest publishing house in Serbia, announced the release of a second edition of John Updike’s Rabbit, Run in June 2018—39 years after the first edition of the novel was published in Serbian.

The first edition was published after Updike visited Serbia in 1978; the second is timed to take advantage of new interest in John Updike in Serbia as a result of the Faculty of Philology, University of Belgrade, hosting the Fifth Biennial John Updike Society Conference, featuring Ian McEwan as the opening keynote speaker.

The translation is by Nevena Stefanović–Čičanović, the same as for the one published in 1979, with an afterword by Prof. Biljana Dojčinović, who is directing the Updike conference.

Dojčinović said that there is a very good chance the new edition of Rabbit, Run will be in bookstore windows when conference attendees are exploring Belgrade.

“John Updike,” for those who don’t read Serbian, is “Džon Apdajk.” Here’s a link to the announcement.