Amazon is now accepting pre-orders for A Theology of Sense: John Updike, Embodiment, and Late Twentieth-Century American Literature, by Scott Dill. The hardcover volume runs 198 pages, with a suggested retail price of $64.95 from The Ohio State University Press. The monograph will be published on November 13, 2018.

Amazon is now accepting pre-orders for A Theology of Sense: John Updike, Embodiment, and Late Twentieth-Century American Literature, by Scott Dill. The hardcover volume runs 198 pages, with a suggested retail price of $64.95 from The Ohio State University Press. The monograph will be published on November 13, 2018.

From the press:

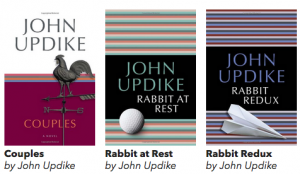

“Scott Dill’s A Theology of Sense: John Updike, Embodiment, and Late Twentieth-Century American Literature brings together theology, aesthetics, and the body, arguing that Updike, a central figure in post-1945 American literature, deeply embeds in his work questions of the body and the senses with questions of theology. Dill offers new understandings not only of the work of Updike—which is importantly being revisited since the author’s death in 2009—but also new understandings of the relationship between aesthetics, religion, and physical experience.

“Dill explores Updike’s unique literary legacy in order to argue for a genuinely postsecular theory of aesthetic experience. Each chapter takes up one of the five senses and its relation to broader theoretical concerns: affect, subjectivity, ontology, ethics, and theology. While placing Updike’s work in relation to other late twentieth- century American writers, Dill explains their notions of embodiment and uses them to render a new account of postsecular aesthetics. No other novelist has portrayed mere sense experience as carefully, as extensively, or as theologically—repeatedly turning to the doctrine of creation as his stylistic justification. Across this examination of his many stories, novels, poems, and essays, Dill proves that Updike forces us to reconsider the power of literature to revitalize sense experience as a theological question.”

From Updike scholar James Schiff:

“One of the finest, most original monographs I’ve read on Updike. Dill covers new ground in approaching Updike’s work through sensory aesthetics, carving out a path that others may wish to follow. Further, he persuasively counters many of the criticisms that have over the years been leveled against Updike.”

From Mark Eaton, co-editor, The Gift of Story: Narrating Hope in a Postmodern World:

“This book will considerably deepen our understanding of how Updike developed a unique ‘theology of sense’ out of his lifelong reading of Christian theology and religious history, not to mention his longstanding devotion to practice.”

Dill, who teaches at Case Western Reserve University, is an active member of The John Updike Society. He recently took part in the closing panel of The Fifth Biennial John Updike Society Conference at the National Library of Serbia: “Updike & Politics: Does Rabbit Angstrom’s Political Evolution Help to Explain Trump Supporters?”