In spring 2023, Jay Brooks of the Brookston Beer Bulletin celebrated “John Updike’s Paean To The Beer Can” and included Updike’s often-anthologized Talk of the Town mini-essay on the Great American Container.

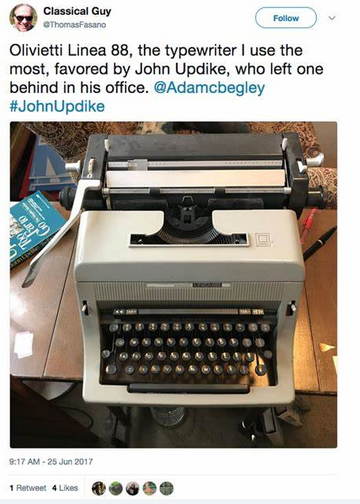

“He grew up in the same small Pennsylvania town that I did—Shillington—and we both escaped to a life of writing,” Brooks wrote. “Though I think you’ll agree he did rather better than I did with the writing thing, not that I’m complaining. I once wrote to him about a harebrained idea I had about writing updated Olinger stories from the perspective of the next generation (his Olinger Stories were a series of short tales set in Olinger, which was essentially his fictional name for Shillington). He wrote me back a nice note of encouragement on a hand-typed postcard that he signed, which today hangs in my office as a reminder and for inspiration.”

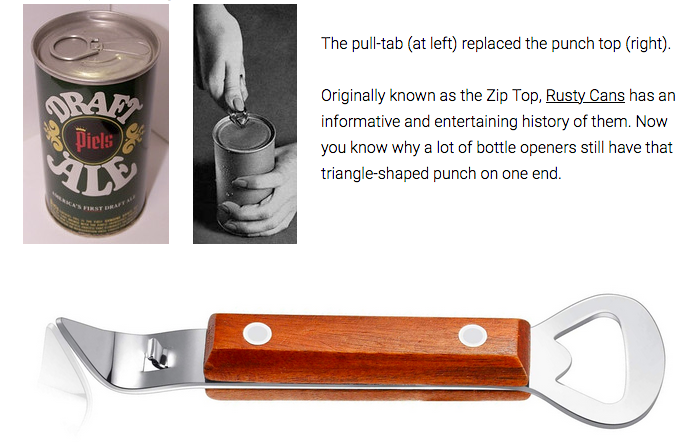

Brooks then shared Updike’s very short musings on the “Beer Can” and noted that “essentially, he’s lamenting the death of the old style beer can which most people considered a pain to open and downright impossible should you be without the necessary church key opener. He is correct, however, that the newfangled suckers were sharp and did cut fingers and lips on occasion, even snapping off without opening from time to time. But you still have to laugh at the unwillingness to embrace change (and possibly progress) even though he was only 32 at the time; hardly a normally curmudgeonly age.”

In Updike’s defense, he did end his mini-essay by saying, “What we need is Progress with an escape hatch.”