In a post titled “The Despair of Atheism and the Hope of Christianity” on his Thinking on Scripture blog, Dr. Steven R. Cook wrote,

“Consider also this view of death by the atheist John Updike, from his novel, Pigeon Feathers:”

Wait. The atheist John Updike?

It’s easy enough for non-literary folks to confuse a short story collection with a novel, but confusing a writer almost universally hailed as a Christian writer with an atheist? Let’s be clear here. Though dictionaries define “atheism” as simply “disbelief or lack of belief in the existence of God or gods,” it must necessarily involve something more extreme—a rejection of God or the existence of God, perhaps, or else all of Christendom are atheists. For who hasn’t had at least one moment of fearful doubt, the frightening kind of “What if there is no God?” thought that threw deep thinkers like the existentialists into the throes of despair? Didn’t Christ also experience a moment of despair and lack of faith while dying on the cross: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

Below is the passage that Dr. Cook was introducing:

“Without warning, David was visited by an exact vision of death: a long hole in the ground, no wider than your body, down which you were drawn while the white faces above recede. You try to reach them but your arms are pinned. Shovels pour dirt in your face. There you will be forever, in an upright position, blind and silent, and in time no one will remember you, and you will never be called by any angel. As strata of rock shift, your fingers elongate, and your teeth are distended sideways in a great underground grimace indistinguishable from a strip of chalk. And the earth tumbles on, and the sun expires, an unaltering darkness reigns where once there were stars.”

This was 14-year-old David Kern during his moment-on-the-cross despair. Later in the story, however, David experienced an epiphany and a return to faith . . . and to hope.

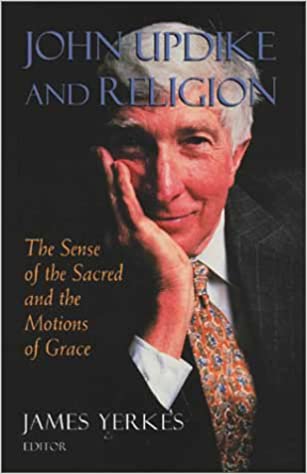

The John Updike Society has so many members who are ministers precisely because Updike—a Lutheran who married a minister’s daughter—is a Christian writer who writes honestly about what it really means to be a Christian and to wrestle with doubts. Even the admission of doubt is an act of faith, for doubt is uncertainty, not disbelief. As many Updike scholars have observed and even Wikipedia noted, “Updike’s novels often act as dialectical theological debates between the book itself and the reader….”

“Updike’s faith is Christian,” Bernard A. Schopen wrote some 16 years after Pigeon Feathers was published in book form, “but it is one to which many of the assumptions about the Christian perspective do not apply—especially those which link Christian faith with an absolute and divinely ordered morality.” In Updike’s fictional world, faith is not absolute, nor is it constant. It is perpetual, but broken (balanced?) by doubts that occupy his heroes as they hope for grace.

As Updike wrote in the November 29, 1999 New Yorker, “Faith is not so much a binary pole as a quantum state, which tends to indeterminacy when closely examined. At the end of the millennium, and of a century that has the Holocaust at its center, the reasons for doubt in God’s existence are so easily come by….” Wavering faith is the rule in Updike’s fictional world, not the exception. But wavering faith and atheism are not the same.

Thank you for your article. After further review of John Updike, I have removed the quote from my article. Though I question Updike’s view of Christianity, I realize the quote did not accurately reflect his beliefs. The correction has been made. https://thinkingonscripture.com/2022/01/15/the-despair-of-atheism-and-the-hope-of-christianity/