Feel like playing 21 questions, literature-style? The Guardian is counting on it, and you can test your Updike knowledge on Question #10:

There is no “reveal,” unless you go to The Guardian to take the quiz and see how you fared!

Feel like playing 21 questions, literature-style? The Guardian is counting on it, and you can test your Updike knowledge on Question #10:

There is no “reveal,” unless you go to The Guardian to take the quiz and see how you fared!

Boston’s North Shore newspaper, The Local News, dipped into the area’s Updike past for a Dec. 24, 2024 installment of “This Week in Ipswich’s Old News (Dec. 19-25). Here’s the entry from current News editor Trevor Meek:

December 24, 1964

Author John Updike returns to Ipswich after a two-month trip to the Soviet Union, which was arranged through the State Department’s cultural exchange program.

He was joined on the trip by author John Cheever.

“We have ‘boy meets girl’ novels. Well, in the Soviet Union, it was ‘boy meets tractor,’” Updike said.

“The Russians, he noted, were naturally hospitable, and he said Americans were ‘the only people in the world that the Soviets feel they can talk to as equals.’” (Ipswich Chronicle)

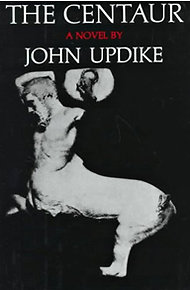

The Greatest Books website recently added a “comprehensive and trusted” list on “The  Greatest Books of All Time on Teachers,” and it’s no surprise that John Updike’s 1963 novel, The Centaur, ranks high on the list. His tribute to his father (and teacher), Wesley Updike, did win the National Book Award, after all.

Greatest Books of All Time on Teachers,” and it’s no surprise that John Updike’s 1963 novel, The Centaur, ranks high on the list. His tribute to his father (and teacher), Wesley Updike, did win the National Book Award, after all.

Who took the #1 spot, according to the site’s algorithm?

Candide, by Voltaire, with Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White coming in second, and Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie placing third. Here’s the rest of the list.

If you’ve been accustomed to getting your Updike Society and John Updike Childhood Home news through Facebook, you might want to bookmark our webpages for future use instead. Yesterday Facebook suspended both sites because it was determined that they were guilty of celebrity “impersonation.” This, even after an appeal.

Seriously? A non-profit literary organization largely composed of academics, along with a museum that’s on the National Register of Historic Places and has a Pennsylvania Historic Marker?

Clearly, Facebook “Meta” is more omnipotent than it is omniscient.

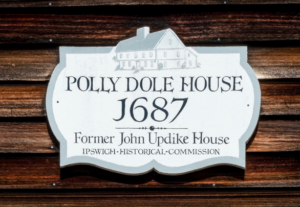

The Local News reported that J. Barrett Realty just listed the Polly Dole house on 25 East Street—the second house John and Mary Updike lived in after they moved to the Ipswich area—for sale at $729,000. It’s the first time the house has been listed in 30 years.

Photo: J. Barrett Realty

The Updikes bought the house in 1958, a year before his first novel (The Poorhouse Fair) and first short story collection (The Same Door) were published by Knopf. The purchase, he told a New Yorker editor, made him feeling “quite panicked” because of mortgage payments that, for a writer still trying to establish himself, could be burdensome.

As Local News reporter Trevor Meek wrote, fictional versions of the Polly Dole house appeared in many of Updike’s short stories, “most notably in the ‘Maples Stories’ that trace the doomed-to-fail marriage of recurring characters Joan and Richard Maple,” and the “house inhabited by Angela and Piet Hanema, central characters in Updike’s controversial novel Couples (1968), also seems to be based on the East Street home.” Publication of the latter caused a row in Ipswich because people in this small North Shore town recognized elements of themselves in the novel, prompting the Updikes to move to London for a year to let things calm down.

In 1969, John and Mary sold the Polly Dole house to Alexander and Martha Bernhard. Meek quoted biographer Adam Begley’s succinct summary of what happened next: “Soon, the Bernhards were part of the gang, and several years later John and Martha launched into an affair that broke up both marriages.”

Photo: J. Barrett Realty

Updike had jokingly told his young children that a big nut on the ceiling that had been turned to straighten the house was holding the house together, and if it was loosened the whole house might collapse. “Once we moved, the fact is, things fell apart,” Updike wrote in Architectural Digest.

According to the Historic Ipswich, the Polly Dole house has “elements from 1687, but acquired its current form in 1720.” Meek noted, “At 2,942 square feet, it sits on 0.24 acres and is being advertised as a multi-family home with two separate side-by-side units. The house last sold in 1995 for $238,000, according to property tax records.”

With heavy hearts we report the death of longtime John Updike Society member Andrew J. Moorhouse, whom many members first met when he attended the society’s second biennial conference in Boston in 2012.

With heavy hearts we report the death of longtime John Updike Society member Andrew J. Moorhouse, whom many members first met when he attended the society’s second biennial conference in Boston in 2012.

According to a post his family created on his Facebook page, Andrew “died peacefully on Tuesday, September 24, after a year of ill health and a short-lived battle with a secondary CNS lymphoma which took root in his brain.

“Andrew would have used his unique talent with words to craft this message full of beautiful allegories, imagery and metaphors but sadly we have neither his brains nor his brilliance.

“Many will know Andrew through his Facebook and social media, which he used to connect with like-minded people across the world. Andrew was a generous and loving husband, father, brother and friend. As well as a loyal Dale fan. He will be greatly missed.”

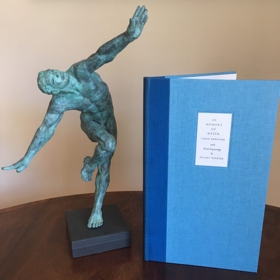

Updike Society members will certainly miss him. Andrew was a gentle and quiet force of nature who, members may recall, was fresh off of a kidney transplant when he talked about becoming a fine letterpress edition publisher of poetry. As he told Body online literary magazine in 2021,

“I have always been a keen reader. My favorite authors generally are American novelists but also British poets. A collector too. I like beautifully printed and bound signed, limited editions. I collected John Updike’s books—it was Updike who said: ‘a book is beautiful in its relation to the human hand, its relation to the human eye, to the human brain, and to the human spirit.’ I felt the same way.”

Inspired by Updike and Updike small-press limited edition publisher William Ewert, Andrew contacted UK Poet Laureate Simon Armitage, whose work he collected, asking if he’d be interested in working with him to produce fine press editions of his works. Armitage was interested, and in October 2013, Andrew started Fine Press Poetry and officially became a small press publisher with his first book, In Memory of Water, poems by Armitage. Many more books followed.

Inspired by Updike and Updike small-press limited edition publisher William Ewert, Andrew contacted UK Poet Laureate Simon Armitage, whose work he collected, asking if he’d be interested in working with him to produce fine press editions of his works. Armitage was interested, and in October 2013, Andrew started Fine Press Poetry and officially became a small press publisher with his first book, In Memory of Water, poems by Armitage. Many more books followed.

Andrew was indeed an insightful reader of Updike who could talk about Updike’s books on the same level as any Ph.D. or much-published scholar. He was interesting and intelligent and a delight to be around. The John Updike Society is poorer without him, and we offer our condolences to his family: Rosie, Rebecca, and James. He made the world a better place.

Chase Replogle, pastor of Bent Oak Church in Springfield, Mo., posted a chapter excerpt that didn’t make the final cut of his book, A Sharp Compassion. “I think it still matters, he wrote. “It is taken from the chapter on affirmation and examines how the church has been tempted to avoid what offends.”

Chase Replogle, pastor of Bent Oak Church in Springfield, Mo., posted a chapter excerpt that didn’t make the final cut of his book, A Sharp Compassion. “I think it still matters, he wrote. “It is taken from the chapter on affirmation and examines how the church has been tempted to avoid what offends.”

In comparing Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and John Updike’s Rabbit, Run, which Updike said was written in part as a response to Kerouac’s novel, he notes, “Both novels talk plenty about God. Both raise questions Americans have historically turned to the church to help answer. But Updike alone recognizes the unique temptation the church faces.

“In Updike’s novel, Rabbit genuinely believes that abandoning his family is a kind of spiritual pursuit to find himself. He explains to his pastor, ‘Well I don’t know all this about theology, but I’ll tell you. I do feel, I guess that somewhere behind all this… there’s something that wants me to find it!’ His pastor, Jack Eccles, works tirelessly to reconcile Rabbit with his estranged wife, but Eccles has his own insecurities. He is convinced that his clerical robe and collar rob him of relatability and cost him Rabbit’s genuine respect. He feels he isn’t relevant to Rabbit’s life and interests. His pastoral insecurities lead him to covet Rabbit’s friendship. He imagines that being Rabbit’s friend is an essential prerequisite to leading him back to faith.”

Read the entire excerpt from A Sharp Compassion.

In “‘The Most Sympathetic Reader You Can Imagine’: William Maxwell’s New Yorker and the Midcentury Short Story,” Ben Fried described, essentially, how even a light-handed editor can have a tremendous influence on writers and published literature.

In “‘The Most Sympathetic Reader You Can Imagine’: William Maxwell’s New Yorker and the Midcentury Short Story,” Ben Fried described, essentially, how even a light-handed editor can have a tremendous influence on writers and published literature.

“One editor among several,” Fried wrote, “Maxwell’s selection and revision of texts took place against the backdrop of “the New Yorker story,” that enduring stereotype which, while considerably oversimplified, nevertheless captures the magazine’s penchant for conventionally realist stories chronicling the domestic lives of a white upper middle class — a demographic that, not coincidentally, overlapped with the editors themselves. Maxwell alternately heeded and bucked this aesthetic and social current, although he did little to disturb its racial homogeneity. The archival records of Updike’s stories of Pennsylvania boyhood, of Cheever’s increasingly experimental fiction, and of Gallant’s Linnet Muir series reveal both the scope and the limits of the editor’s sympathetic reading. I argue that Maxwell at once enforced and expanded the company line, reluctantly policing The New Yorker‘s more rigid notions of realism while drawing ever more wide-ranging autobiographical story sequences from a constellation of writers.”

Literary tourism just took a flavorful turn.

Phoenixville (Chester County) Pa.’s Excursion Ciders “uses local apples that are presssed and made in-house, also utilizing other locally-grown ingredients to make their drinks. Currently, the star of the show is Of the Farm: Core. This cider has an ABV of 7.5 percent and is made with apples from Plowville Orchard. Author John Updike spent time there and they named this cider after his novel, Of the Farm.” Here’s the link to the full story.

Phoenixville (Chester County) Pa.’s Excursion Ciders “uses local apples that are presssed and made in-house, also utilizing other locally-grown ingredients to make their drinks. Currently, the star of the show is Of the Farm: Core. This cider has an ABV of 7.5 percent and is made with apples from Plowville Orchard. Author John Updike spent time there and they named this cider after his novel, Of the Farm.” Here’s the link to the full story.

Of course, Weaver’s Orchard in Morgantown is the Updike site in Plowville for apples. The Updikes sold land to the Weavers, and one of the Weaver family owns and lives in the Updike ancestral farmhouse in Plowville and also spoke to our members at two conferences.

In “25 Best Books About Witches to Read in 2024: Spellbinding Books Filled with Magic and Mystery,” Marilyn Walters made John Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick her sixth pick. Topping the list was Circe by Madeline Miller, Practical Magic by Alice Hoffman, The Witching Hour by Anne Rice, The Familiars by Stacey Halls, and Hex by Thomas Olde Heuvelt.

“In the small town of Eastwick, Rhode Island, three women — Alexandra, Jane, and Sukie — discover they have magical powers after their marriages end.

“In the small town of Eastwick, Rhode Island, three women — Alexandra, Jane, and Sukie — discover they have magical powers after their marriages end.

“Their abilities get stronger when a mysterious man, Darryl Van Horne, comes to town and encourages their witchcraft. As they form a coven and use their magic, their actions lead to severe problems, including murder and chaos.

“The novel looks at themes of power, freedom, and the supernatural with a darkly funny twist. Set in the early 1970s, it reflects the social changes and liberal attitudes of the time.”

Here’s the link to the rest of the 25—24, actually, since one entry is a duplicate.