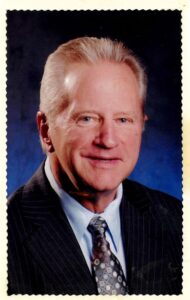

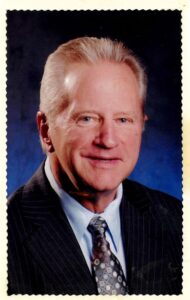

With heavy hearts we report that the senior docent of The John Updike Childhood Home, David W. Ruoff, died Jan. 1 at age 83 of congestive heart failure while in hospice care in Ephrata. Dave became a member of The John Updike Society in 2012 after he began renting the single-story annex to The John Updike Childhood Home, back when it was still a deconstruction zone.

With heavy hearts we report that the senior docent of The John Updike Childhood Home, David W. Ruoff, died Jan. 1 at age 83 of congestive heart failure while in hospice care in Ephrata. Dave became a member of The John Updike Society in 2012 after he began renting the single-story annex to The John Updike Childhood Home, back when it was still a deconstruction zone.

From the beginning, though, Dave was more than a renter. He became a great friend to society president James Plath, who traveled from Illinois to Shillington to work on the house several times each year over the course of the decade it took to restore the house to be historically accurate and to create a museum Berks County could be proud of. Dave loved Updike and was willing to help any way he could. He began by receiving items shipped to the society and by giving impromptu tours to people who came to the house, telling them how he grew up on Philadelphia Ave. just two blocks from the Updike house at 117.

Dave loved regaling visitors with stories about Updike’s father, Wesley, whom he had for a teacher, and he loved going the extra mile and giving people who had traveled to Shillington from abroad or great distances samples of Berks County ring bologna and Tom Sturgis pretzels—the latter, Updike’s favorite. Sometimes, if they asked for directions to Plowville, Dave would even drive them . . . after first showing them the Updike sites in Shillington that they might have otherwise missed. And when an alarm would go off in the middle of the night, Dave, one of three people with a key, always volunteered to get his coat and gun and drive over to make sure everything was all right.

Although it takes a village to create a museum that’s listed on the National Register of Historic Places and has a Pennsylvania Historic Marker—a museum that The Wall Street Journal last year called “a worthy site of literary pilgrimage”—Dave was part of a core group most responsible for the museum’s creation and operation. In addition, numerous people over the years have made donations to the society based on their interaction with Dave, whose community pride and passion for Updike was contagious.

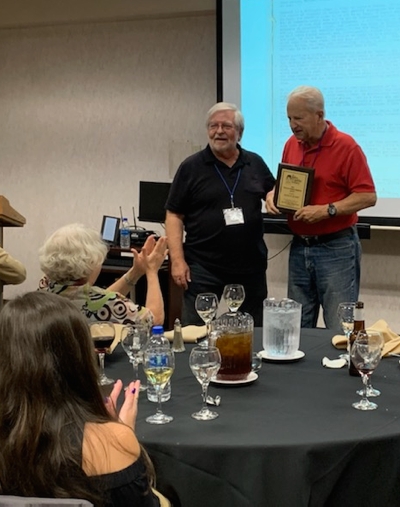

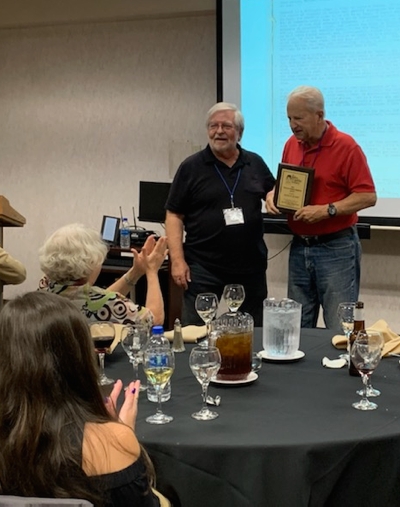

The society loved him back. On October 2, 2021, the board honored him as the sixth recipient of The John Updike Society Distinguished Service Award, praising his “extraordinary docent work and other services to The John Updike Childhood Home.” Dave was funny, generous, thoughtful, and a little bit larger than life. He’ll be greatly missed.

The society loved him back. On October 2, 2021, the board honored him as the sixth recipient of The John Updike Society Distinguished Service Award, praising his “extraordinary docent work and other services to The John Updike Childhood Home.” Dave was funny, generous, thoughtful, and a little bit larger than life. He’ll be greatly missed.

The obituary notes that Dave graduated from Gov. Mifflin High School in 1959 as a double athlete (football and wrestling), served in the Army with the 82nd Airbourne, and was a “proud member of the Special Forces as a Green Beret.” Dave was in the insurance business for 55 years and loved hunting, biking, and spending time with his family. Here is the full obituary, which details where donations can be made.

Our deepest sympathies go to his wife, Maria, daughter Tara, son Jim, grandchildren Zack, Cole and Rayne, great-grandchildren Tanner and Beckett, and all members of the Ruoff extended family.

Updike Society member Lang Zimmerman was reading Salman Rushdie’s Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder (Random House, 2024) when he came upon a second-chapter account of the birth of the PEN America World Voices Festival:

Updike Society member Lang Zimmerman was reading Salman Rushdie’s Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder (Random House, 2024) when he came upon a second-chapter account of the birth of the PEN America World Voices Festival:

Jeff Werner, of

Jeff Werner, of  As his Reading Eagle

As his Reading Eagle  Displays will include founding documents, rare manuscripts, photos, cover and cartoon art, and artifacts on loan from other institutions–all intended to take visitors “behind the scenes of the making of one of the United States’s most important magazines,” according to City Life Org.

Displays will include founding documents, rare manuscripts, photos, cover and cartoon art, and artifacts on loan from other institutions–all intended to take visitors “behind the scenes of the making of one of the United States’s most important magazines,” according to City Life Org. Ditum reminded readers of the impetus behind Updike’s writing of the novel: “Jack Kerouac’s On the Road came out in 1957, and without reading it, I resented its apparent injunction to cut loose; Rabbit, Run was meant to be a realistic demonstration of what happens when a young American man goes on the road—the people left behind get hurt. There was no painless dropping out of the Fifties’ fraying but still tight social weave.”

Ditum reminded readers of the impetus behind Updike’s writing of the novel: “Jack Kerouac’s On the Road came out in 1957, and without reading it, I resented its apparent injunction to cut loose; Rabbit, Run was meant to be a realistic demonstration of what happens when a young American man goes on the road—the people left behind get hurt. There was no painless dropping out of the Fifties’ fraying but still tight social weave.” Leslie Pietrzyk, whose first collection of short stories, The Angel on My Chest, won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize, was selected over 193 applicants to be the 2025 John Updike Tucson Casitas Fellow. The fellowship consists of a $1000 prize from The John Updike Society and a two-week residency at the casitas formerly owned by John and Martha Updike, where the two-time Pulitzer Prize winner spent time golfing and writing in his later years. The casitas, located in the Santa Catalina Foothills, are owned by Jan and Jim Emery, and the annual residency is made possible by their generosity. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Leslie Pietrzyk, whose first collection of short stories, The Angel on My Chest, won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize, was selected over 193 applicants to be the 2025 John Updike Tucson Casitas Fellow. The fellowship consists of a $1000 prize from The John Updike Society and a two-week residency at the casitas formerly owned by John and Martha Updike, where the two-time Pulitzer Prize winner spent time golfing and writing in his later years. The casitas, located in the Santa Catalina Foothills, are owned by Jan and Jim Emery, and the annual residency is made possible by their generosity. (Photo: Wikipedia)

With heavy hearts we report that the senior docent of The John Updike Childhood Home, David W. Ruoff, died Jan. 1 at age 83 of congestive heart failure while in hospice care in Ephrata. Dave became a member of The John Updike Society in 2012 after he began renting the single-story annex to The John Updike Childhood Home, back when it was still a deconstruction zone.

With heavy hearts we report that the senior docent of The John Updike Childhood Home, David W. Ruoff, died Jan. 1 at age 83 of congestive heart failure while in hospice care in Ephrata. Dave became a member of The John Updike Society in 2012 after he began renting the single-story annex to The John Updike Childhood Home, back when it was still a deconstruction zone. The society loved him back. On October 2, 2021, the board honored him as the sixth recipient of The John Updike Society Distinguished Service Award, praising his “extraordinary docent work and other services to The John Updike Childhood Home.” Dave was funny, generous, thoughtful, and a little bit larger than life. He’ll be greatly missed.

The society loved him back. On October 2, 2021, the board honored him as the sixth recipient of The John Updike Society Distinguished Service Award, praising his “extraordinary docent work and other services to The John Updike Childhood Home.” Dave was funny, generous, thoughtful, and a little bit larger than life. He’ll be greatly missed. course, played an important role for a lot writers—no need to list them all here.) John Ashbery enjoyed a nice cup of tea and classical music when he wrote, which was usually in the late afternoon. Charles Simic enjoyed writing when his wife was cooking. Eudora Welty could write anywhere—even in the car— and at any time, except at night when she was socializing. Flannery O’Connor could only write two hours a day and her drink was Coca Cola mixed with coffee. Simone de Beauvoir wrote from 10AM-1PM and from 5-9PM. Louise Glück found writing on a schedule “an annihilating experience.” A. R. Ammons wrote only when inspiration hit—he compared trying to write to trying to force yourself to go the bathroom when you have no urge. Anne Sexton took up writing after therapy sessions. Jack Kerouac had various rituals at different times—one was writing by candlelight, and another was doing “touch downs” which involved standing on his head and touching his toes to the ground. Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf wrote standing up. Wallace Stevens composed poems while walking to work. Gabriel García Márquez listened to the news before writing. Amy Gerstler sometimes listens to recordings of rain while writing. I tried that once, and the rain put me into a deep and dreamless sleep.”

course, played an important role for a lot writers—no need to list them all here.) John Ashbery enjoyed a nice cup of tea and classical music when he wrote, which was usually in the late afternoon. Charles Simic enjoyed writing when his wife was cooking. Eudora Welty could write anywhere—even in the car— and at any time, except at night when she was socializing. Flannery O’Connor could only write two hours a day and her drink was Coca Cola mixed with coffee. Simone de Beauvoir wrote from 10AM-1PM and from 5-9PM. Louise Glück found writing on a schedule “an annihilating experience.” A. R. Ammons wrote only when inspiration hit—he compared trying to write to trying to force yourself to go the bathroom when you have no urge. Anne Sexton took up writing after therapy sessions. Jack Kerouac had various rituals at different times—one was writing by candlelight, and another was doing “touch downs” which involved standing on his head and touching his toes to the ground. Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf wrote standing up. Wallace Stevens composed poems while walking to work. Gabriel García Márquez listened to the news before writing. Amy Gerstler sometimes listens to recordings of rain while writing. I tried that once, and the rain put me into a deep and dreamless sleep.”