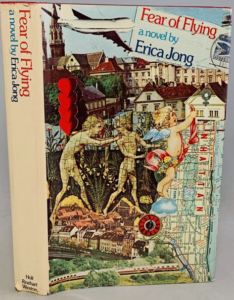

As part of their feminist classics series which looks at influential books, The Conversation featured an article on “Sex, zips and feminism: Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying has a joyful abandon rarely found in today’s sad girl novels” in which John Updike was quoted.

As part of their feminist classics series which looks at influential books, The Conversation featured an article on “Sex, zips and feminism: Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying has a joyful abandon rarely found in today’s sad girl novels” in which John Updike was quoted.

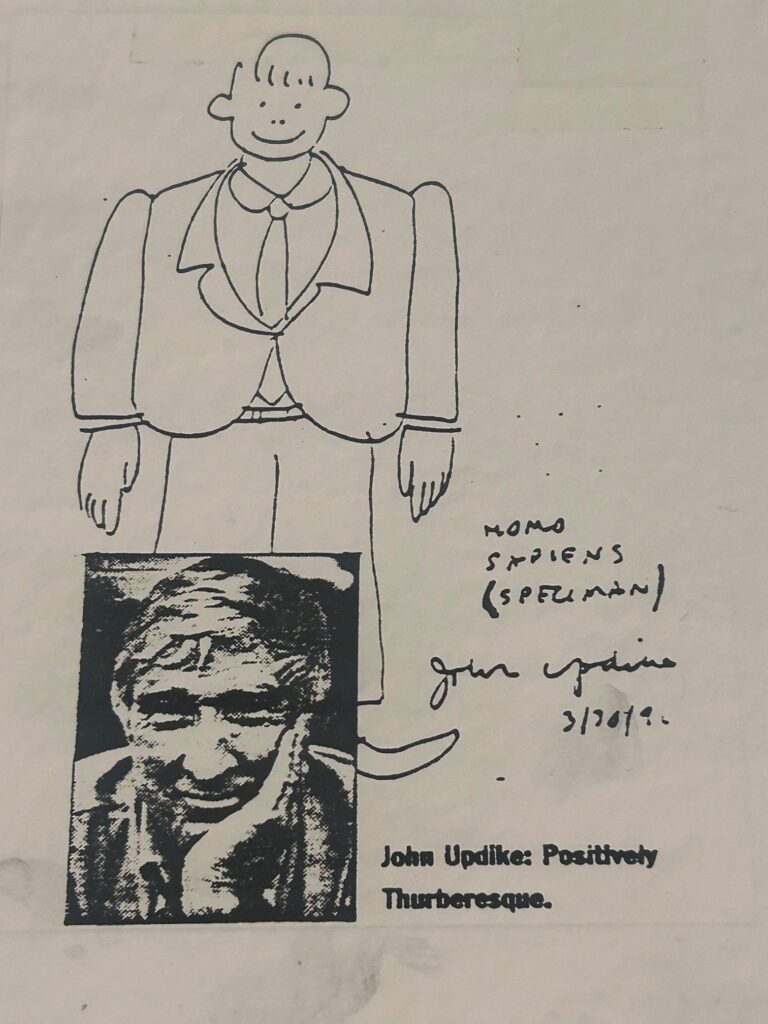

“Interestingly though, another male writer, John Updike, helped Jong’s rise up the bestseller list. Even so, his compliments can read as backhanded as Goodlove’s:

It has class and sass, brightness and bite. Containing all the cracked eggs of the feminist litany, her soufflé rises with a poet’s afflatus. She sprinkles on the four-letter words as if women had invented them; her cheerful sexual frankness brings a new flavor to female prose.

“Updike favourably links Jong with great male writers J.D. Salinger and Philip Roth, while carefully distinguishing her from the more disagreeable women’s liberationists:

Fear of Flying not only stands as a notably luxuriant and glowing bloom in the sometimes thistly garden of ‘raised’ feminine consciousness but belongs to, and hilariously extends, the tradition of Catcher in the Rye and Portnoy’s Complaint.

“Pull quotes from Updike’s review featured on the novel’s second edition (the one I have been reading), along with a new cover: a luscious 70s serif typeface in black and orange on a yellow background that blatantly copies the 1969 cover of Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint.”

The editors decided to define “American” as having been first published in the U.S., they narrowed the field to the past 100 years (“a period that began as literary modernism was cresting”), and they approached “scholars, critics, and novelists, both at The Atlantic and outside it” asking for suggestions. Their aim: “the very best—novels that say something intriguing about the world and do it distinctively, in intentional, artful prose.” That resulted in a list of 136 books, and if you break that list down by decades it looks like this: 7 from the ’20s, 9 from the ’30s, 7 from the ’40s, 13 from the ’50s, 15 from the ’60s, 19 from the ’70s, 12 from the ’80s, 16 from the ’90s, 14 from the ’00s, 21 from the ’10s, and 3 from the current young decade—reflecting, perhaps, a fairly large familiarity factor based on the ages of those who weighed in.

The editors decided to define “American” as having been first published in the U.S., they narrowed the field to the past 100 years (“a period that began as literary modernism was cresting”), and they approached “scholars, critics, and novelists, both at The Atlantic and outside it” asking for suggestions. Their aim: “the very best—novels that say something intriguing about the world and do it distinctively, in intentional, artful prose.” That resulted in a list of 136 books, and if you break that list down by decades it looks like this: 7 from the ’20s, 9 from the ’30s, 7 from the ’40s, 13 from the ’50s, 15 from the ’60s, 19 from the ’70s, 12 from the ’80s, 16 from the ’90s, 14 from the ’00s, 21 from the ’10s, and 3 from the current young decade—reflecting, perhaps, a fairly large familiarity factor based on the ages of those who weighed in. The online

The online  Myrtle was a 1941 graduate of Shillington High School, and after serving in the Navy WAVES during WWII she worked at the Reading Eagle-Times, Jacobs Aircraft Engineering Co., and Edelman’s Law Office in Reading.

Myrtle was a 1941 graduate of Shillington High School, and after serving in the Navy WAVES during WWII she worked at the Reading Eagle-Times, Jacobs Aircraft Engineering Co., and Edelman’s Law Office in Reading. The selection committee for the John Updike Tucson Casitas Fellowship has chosen Dr. Sue Norton, Lecturer of English in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at Technological University Dublin, to serve as the first fellow in residence.

The selection committee for the John Updike Tucson Casitas Fellowship has chosen Dr. Sue Norton, Lecturer of English in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at Technological University Dublin, to serve as the first fellow in residence. Laurence W. Mazzeno: Contemporary American Fiction in the European Clasroom: Teaching and Texts (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022) and European Perspectives on John Updike (Camden House, 2018). Norton came to Updike studies through her doctoral work on family in contemporary American fiction, which she completed in 2001 at University College Dublin. Her first article on Updike (The John Updike Review, 2014) was on the “regulating daughter” in the Rabbit novels. She has maintained an interest in the treatment of girls and women in Updike’s writing and beyond. It is on this topic that she will focus during her residency as the 2024 Fellow at the Tucson Casitas.

Laurence W. Mazzeno: Contemporary American Fiction in the European Clasroom: Teaching and Texts (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022) and European Perspectives on John Updike (Camden House, 2018). Norton came to Updike studies through her doctoral work on family in contemporary American fiction, which she completed in 2001 at University College Dublin. Her first article on Updike (The John Updike Review, 2014) was on the “regulating daughter” in the Rabbit novels. She has maintained an interest in the treatment of girls and women in Updike’s writing and beyond. It is on this topic that she will focus during her residency as the 2024 Fellow at the Tucson Casitas. James Plath, whose most recent published criticism—”Updike’s ‘Wife-Wooing’: The Seven Year Itch and the Soliloquy of Seduction”—appeared in The John Updike Review Vol. 10, No. 1 (Fall 2023), recently spent two weeks researching an essay on Mark Twain and John Updike as a Quarry Farm Fellow.

James Plath, whose most recent published criticism—”Updike’s ‘Wife-Wooing’: The Seven Year Itch and the Soliloquy of Seduction”—appeared in The John Updike Review Vol. 10, No. 1 (Fall 2023), recently spent two weeks researching an essay on Mark Twain and John Updike as a Quarry Farm Fellow. ABSTRACT: This article provides an innovative perspective on John Updike’s visit to Eastern Europe in the 1960s, including Bulgaria, as reflected in his short story “The Bulgarian Poetess” first published in The New Yorker on March 13, 1965. The inspiration for this interpretation is as much academic as it is anthropological. It comes from Updike’s use of my own surname, Glavanakova, which is not a common Slavic one, for the fictional character of the real-life Bulgarian poetess he met, whom researchers have established to be Blaga Dimitrova. Many have delved into the text aiming at a detailed and, more significantly, an authentic reconstruction of events, places and people appearing in the story (Katsarova 2010; Kosturkov 2012; Briggs and Dojčinović 2015). A main preoccupation of these analyses has been to establish the degree of factual distortion in Updike’s representation of the people and places behind the Iron Curtain. The pervasive imagery of the mirror, implying both its reflecting and doubling function, and the repetitive use of cognates associated with truth and honesty in the story suggest the focus of this article, which falls on the dynamics between authenticity and artifice from the perspective of autofiction by way of illustrating how one culture translates into another “at the opposite side[s] of the world” (Updike, “The Bulgarian Poetess”). In my interpretation, autofiction opens ample spaces for representations and discussions of identity and self-/reflexivity in a transcultural context.

ABSTRACT: This article provides an innovative perspective on John Updike’s visit to Eastern Europe in the 1960s, including Bulgaria, as reflected in his short story “The Bulgarian Poetess” first published in The New Yorker on March 13, 1965. The inspiration for this interpretation is as much academic as it is anthropological. It comes from Updike’s use of my own surname, Glavanakova, which is not a common Slavic one, for the fictional character of the real-life Bulgarian poetess he met, whom researchers have established to be Blaga Dimitrova. Many have delved into the text aiming at a detailed and, more significantly, an authentic reconstruction of events, places and people appearing in the story (Katsarova 2010; Kosturkov 2012; Briggs and Dojčinović 2015). A main preoccupation of these analyses has been to establish the degree of factual distortion in Updike’s representation of the people and places behind the Iron Curtain. The pervasive imagery of the mirror, implying both its reflecting and doubling function, and the repetitive use of cognates associated with truth and honesty in the story suggest the focus of this article, which falls on the dynamics between authenticity and artifice from the perspective of autofiction by way of illustrating how one culture translates into another “at the opposite side[s] of the world” (Updike, “The Bulgarian Poetess”). In my interpretation, autofiction opens ample spaces for representations and discussions of identity and self-/reflexivity in a transcultural context. Not everyone who recognizes themselves in a writer’s fiction or poetry is pleased, but William Ecenbarger took delight in recalling his 1983 interview with John Updike that inspired Updike to write “One More Interview.” Then a writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Ecenbarger managed to score his interview with Updike through the writer’s mother, Linda. It was no ordinary interview.

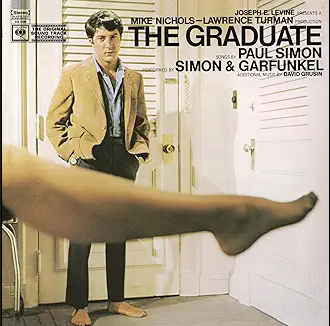

Not everyone who recognizes themselves in a writer’s fiction or poetry is pleased, but William Ecenbarger took delight in recalling his 1983 interview with John Updike that inspired Updike to write “One More Interview.” Then a writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Ecenbarger managed to score his interview with Updike through the writer’s mother, Linda. It was no ordinary interview. Most lists are Top Ten or Top 100, but no one ever accused Art Garfunkel—the quieter half of the Simon & Garfunkel folk-rock duo—of being like “most.” The singer decided to log each book he read, beginning in 1968—the year that the duo’s “Mrs. Robinson,” written for The Graduate soundtrack, won Grammy Record of the Year.

Most lists are Top Ten or Top 100, but no one ever accused Art Garfunkel—the quieter half of the Simon & Garfunkel folk-rock duo—of being like “most.” The singer decided to log each book he read, beginning in 1968—the year that the duo’s “Mrs. Robinson,” written for The Graduate soundtrack, won Grammy Record of the Year.