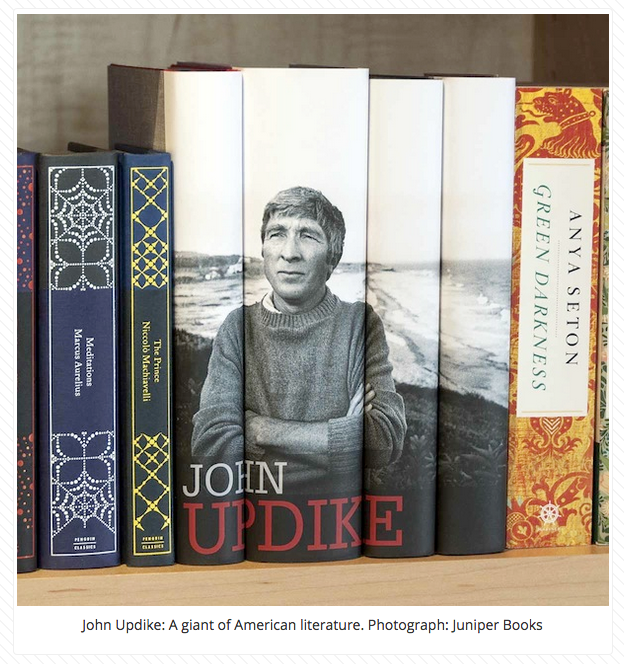

Caleb and Linda Pirtle are writers, and in a recent blogpost they quoted advice from “John Updike: A giant of American literature” that begins with the title: “John Updike: Five pages a day every day of your life.”

Caleb and Linda Pirtle are writers, and in a recent blogpost they quoted advice from “John Updike: A giant of American literature” that begins with the title: “John Updike: Five pages a day every day of your life.”

Writers write. It can be that simple.

“John Updike, he of the bushy eyebrows and hawkish nose, had a distinct style of prose that was described as baroque, exquisite, and prolifically poetic. He did win a couple of Pulitzer Prizes, a pair of National Book Awards, and the Pen/Faulkner Award. And such novels as Couples and Witches of Eastwick, not to mention his quartet of Rabbit Angstrom novels, have a definite place on the top shelf of American literature.

“His name is widely known.

“His work is widely praised.

“Yet, John Updike, the man, was very private. Not a recluse, perhaps, but, it’s said, he cultivated his embowered solitude and would rather sit amidst isolation in his home on the Massachusetts shore and write.

“No one wrote more.

“He left an unending trail of fiction, poetry, essays, and criticism, most of which appeared rather regularly in The New Yorker. In addition, he published almost one book a year for more than a half century.”

Read the advice that Updike gave writers, which Caleb Pirtle passes along.