What kind of person texts photos of their sexual body parts? Don’t pass judgment. The origin of “sexting” goes back at least to 1828 and the story of a “trailblazing miniature portrait artist named Sarah Goodridge and a lawyer named Daniel Webster.” The devil you say?

Goodridge was “smitten with Webster,” wrote Tom Taylor of Far Out Magazine, and “a passion blossomed between and her new favourite subject” as he posed for his portrait. But the artist painted something a little extra and she would “offer the world the first sultry private nude. Obviously, her breasts were far from the first to be cast in watercolour, but they were the first to be painted in a self-portrait fashion and sent off secretly to an admirer—in essence, the exact same as a modern ‘nude’.

“She daubed her bare chest—cast very skillfully in the 3D fashion of optics—and proud pink nipples on a 2.5 x 3.1-inch block of ivory. She then sent this off in a carefully concealed package to Webster who is said to have somehow lifted his desk without the use of his hands when he opened up according to his deputy sitting opposite who was subsequently chaperoned out of the room.”

The piece, now known as Beauty Revealed, is “renowned not only for its place in sultry history but also for its skill and forward-thinking liberation. While the effort may not have won Webster’s hand in marriage, as she may have intended, the pair remained devoted in some way” and the “legacy of her work lives on, as John Updike puts it in the essay ‘The Revealed and the Concealed’: ‘Come to us and we will comfort you, the breasts of her self-portrait seem to say. We are yours for the taking, in all our ivory loveliness, with our tenderly stippled nipples.’ But from less of a male gaze perspective, maybe she was just feeling horny, playful, and frankly, very creative.”

Read the whole article and see the painting.

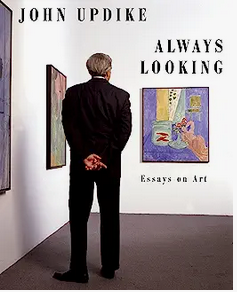

Updike’s essay “The Revealed and the Concealed” was not included in any of his three collected writings on art—Just Looking (1989), Still Looking (2005), or the posthumously published Always Looking (2012).