Bob Batchelor’s podcast John Updike: American Writer, American Life is active again. The new episode is titled “Why You Should Be Reading John Updike: The; Writer Who Predicted Everything.”

From the site: “Hosted by cultural historian and Updike biographer Bob Batchelor, each episode is focused, sharp, and built for listeners who want to dive into the life and career of one of America’s greatest writers.

From the site: “Hosted by cultural historian and Updike biographer Bob Batchelor, each episode is focused, sharp, and built for listeners who want to dive into the life and career of one of America’s greatest writers.

“Updike saw the death of American manufacturing. He wrote about economic anxiety before it became a political movement. He diagnosed the collapse of masculine identity before the culture had a vocabulary for it. He saw the 1970s energy crisis, not as a temporary inconvenience, but as a permanent reckoning with American assumptions about prosperity and progress. And he did it all in beautiful, lyrial sentences.

“He also wrote things that make contemporary readers uncomfortable. His male characters objectify and flee. His perspective is overwhelmingly white and suburban. This podcast doesn’t hide from those tensions. It engages them, because honest conversations about American literature require addressing human complexity, not running from it.

“Each episode takes one aspect of Updike’s life, work, or world and opens it up: the Pennsylvania mill town that shaped him, the New Yorker years that refined his voice, the feminist critique that shadowed his reputation, the beautiful and brutal sentences that remain his most enduring legacy. From the Rabbit novels to Couples to Terrorist—from Updike’s poetry to his art criticism—no corner of the work is off limits.”

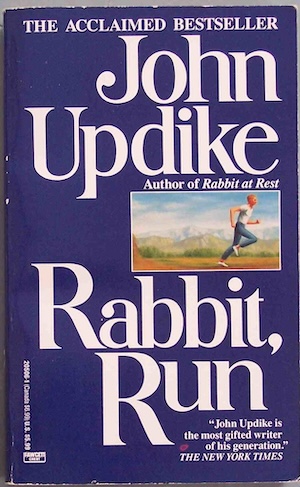

“John Updike’s 1960 novel introduced readers to Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom, perhaps the most iconic character in suburban literature. Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom is a middle-class man who feels there is something missing from his life. The novel follows Rabbit as he flees his suburban responsibilities—his pregnant wife, his job, his entire life—in a desperate attempt to recapture the vitality of his youth. Frank Wheeler, Piet Hanema, Frank Bascombe – these are a handful of the suburban men in the fiction of Richard Yates, John Updike, and Richard Ford. These writers all display certain characteristics of the suburban novel in the post-WWII era: the male experience placed at the forefront of narration, the importance of competition both socially and economically, contrasting feelings of desire and loathing for predictability, and the impact of an increasingly developed landscape upon the American psyche and the individual’s mind. Updike’s genius was in making Rabbit both sympathetic and infuriating—a man whose suburban malaise drives him to make increasingly destructive choices. The novel launched a series that would span four decades, chronicling the evolution of suburban America through one man’s journey.”

“John Updike’s 1960 novel introduced readers to Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom, perhaps the most iconic character in suburban literature. Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom is a middle-class man who feels there is something missing from his life. The novel follows Rabbit as he flees his suburban responsibilities—his pregnant wife, his job, his entire life—in a desperate attempt to recapture the vitality of his youth. Frank Wheeler, Piet Hanema, Frank Bascombe – these are a handful of the suburban men in the fiction of Richard Yates, John Updike, and Richard Ford. These writers all display certain characteristics of the suburban novel in the post-WWII era: the male experience placed at the forefront of narration, the importance of competition both socially and economically, contrasting feelings of desire and loathing for predictability, and the impact of an increasingly developed landscape upon the American psyche and the individual’s mind. Updike’s genius was in making Rabbit both sympathetic and infuriating—a man whose suburban malaise drives him to make increasingly destructive choices. The novel launched a series that would span four decades, chronicling the evolution of suburban America through one man’s journey.” “American novelist John Updike claimed not to write for ego: ‘I think of it more as innocence. A writer must be in some way innocent.’ We might raise an eyebrow at this, from the highly successful and famously intrusive chronicler of human closeness. Even David Foster Wallace, the totem effigy of literary chauvinism, denounced Updike as a ‘phallocrat.’ But if we doubt such innocence of Updike, pronouncing as he was at the flushest height of fiction’s postwar heyday, we might believe it of these new novelists, writing as they are and when they are. Without a promise of glory, and facing general skepticism, they have written from pure motives. They are novelists as Updike defined them: ‘only a reader who was so excited that he tried to imitate and give back the bliss that he enjoyed’.

“American novelist John Updike claimed not to write for ego: ‘I think of it more as innocence. A writer must be in some way innocent.’ We might raise an eyebrow at this, from the highly successful and famously intrusive chronicler of human closeness. Even David Foster Wallace, the totem effigy of literary chauvinism, denounced Updike as a ‘phallocrat.’ But if we doubt such innocence of Updike, pronouncing as he was at the flushest height of fiction’s postwar heyday, we might believe it of these new novelists, writing as they are and when they are. Without a promise of glory, and facing general skepticism, they have written from pure motives. They are novelists as Updike defined them: ‘only a reader who was so excited that he tried to imitate and give back the bliss that he enjoyed’. As part of a grand centennial year celebration, an episode of The New Yorker Radio Hour featured

As part of a grand centennial year celebration, an episode of The New Yorker Radio Hour featured

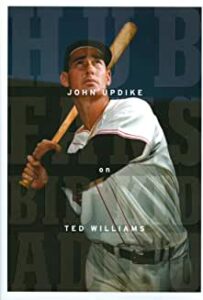

Thomas wrote, “On a dreary Wednesday in September, 1960, John Updike, ‘falling in love, away from marriage,’ took a taxi to see his paramour. But, he later wrote, she didn’t answer his knock, and so he went to a ballgame at Fenway Park for his last chance to see the Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, who was about to retire. For a few dollars, he got a seat behind third base.

Thomas wrote, “On a dreary Wednesday in September, 1960, John Updike, ‘falling in love, away from marriage,’ took a taxi to see his paramour. But, he later wrote, she didn’t answer his knock, and so he went to a ballgame at Fenway Park for his last chance to see the Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, who was about to retire. For a few dollars, he got a seat behind third base.

Ditum reminded readers of the impetus behind Updike’s writing of the novel: “Jack Kerouac’s On the Road came out in 1957, and without reading it, I resented its apparent injunction to cut loose; Rabbit, Run was meant to be a realistic demonstration of what happens when a young American man goes on the road—the people left behind get hurt. There was no painless dropping out of the Fifties’ fraying but still tight social weave.”

Ditum reminded readers of the impetus behind Updike’s writing of the novel: “Jack Kerouac’s On the Road came out in 1957, and without reading it, I resented its apparent injunction to cut loose; Rabbit, Run was meant to be a realistic demonstration of what happens when a young American man goes on the road—the people left behind get hurt. There was no painless dropping out of the Fifties’ fraying but still tight social weave.”