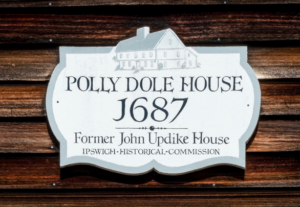

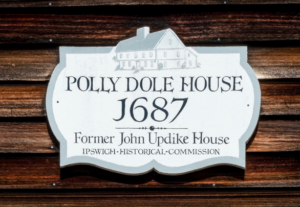

The Local News reported that J. Barrett Realty just listed the Polly Dole house on 25 East Street—the second house John and Mary Updike lived in after they moved to the Ipswich area—for sale at $729,000. It’s the first time the house has been listed in 30 years.

Photo: J. Barrett Realty

The Updikes bought the house in 1958, a year before his first novel (The Poorhouse Fair) and first short story collection (The Same Door) were published by Knopf. The purchase, he told a New Yorker editor, made him feeling “quite panicked” because of mortgage payments that, for a writer still trying to establish himself, could be burdensome.

As Local News reporter Trevor Meek wrote, fictional versions of the Polly Dole house appeared in many of Updike’s short stories, “most notably in the ‘Maples Stories’ that trace the doomed-to-fail marriage of recurring characters Joan and Richard Maple,” and the “house inhabited by Angela and Piet Hanema, central characters in Updike’s controversial novel Couples (1968), also seems to be based on the East Street home.” Publication of the latter caused a row in Ipswich because people in this small North Shore town recognized elements of themselves in the novel, prompting the Updikes to move to London for a year to let things calm down.

In 1969, John and Mary sold the Polly Dole house to Alexander and Martha Bernhard. Meek quoted biographer Adam Begley’s succinct summary of what happened next: “Soon, the Bernhards were part of the gang, and several years later John and Martha launched into an affair that broke up both marriages.”

Photo: J. Barrett Realty

Updike had jokingly told his young children that a big nut on the ceiling that had been turned to straighten the house was holding the house together, and if it was loosened the whole house might collapse. “Once we moved, the fact is, things fell apart,” Updike wrote in Architectural Digest.

According to the Historic Ipswich, the Polly Dole house has “elements from 1687, but acquired its current form in 1720.” Meek noted, “At 2,942 square feet, it sits on 0.24 acres and is being advertised as a multi-family home with two separate side-by-side units. The house last sold in 1995 for $238,000, according to property tax records.”

Jeff Werner, of Patch, writes that the editors of Neshaminy: The Bucks County Historical and Literary Journal nominated two essays for The Pushcart Prizes, as literary magazines are allowed to do. One, by Lee Bigelow Davis and Melissa D. Sullivan, was on “Operation ’64: A Matter of Civic Pride.” The other was an essay by Don Swaim: “John Updike—One Walks by Faith, and One Writes by Faith.”

Jeff Werner, of Patch, writes that the editors of Neshaminy: The Bucks County Historical and Literary Journal nominated two essays for The Pushcart Prizes, as literary magazines are allowed to do. One, by Lee Bigelow Davis and Melissa D. Sullivan, was on “Operation ’64: A Matter of Civic Pride.” The other was an essay by Don Swaim: “John Updike—One Walks by Faith, and One Writes by Faith.”

Displays will include founding documents, rare manuscripts, photos, cover and cartoon art, and artifacts on loan from other institutions–all intended to take visitors “behind the scenes of the making of one of the United States’s most important magazines,” according to City Life Org.

Displays will include founding documents, rare manuscripts, photos, cover and cartoon art, and artifacts on loan from other institutions–all intended to take visitors “behind the scenes of the making of one of the United States’s most important magazines,” according to City Life Org. Ditum reminded readers of the impetus behind Updike’s writing of the novel: “Jack Kerouac’s On the Road came out in 1957, and without reading it, I resented its apparent injunction to cut loose; Rabbit, Run was meant to be a realistic demonstration of what happens when a young American man goes on the road—the people left behind get hurt. There was no painless dropping out of the Fifties’ fraying but still tight social weave.”

Ditum reminded readers of the impetus behind Updike’s writing of the novel: “Jack Kerouac’s On the Road came out in 1957, and without reading it, I resented its apparent injunction to cut loose; Rabbit, Run was meant to be a realistic demonstration of what happens when a young American man goes on the road—the people left behind get hurt. There was no painless dropping out of the Fifties’ fraying but still tight social weave.” course, played an important role for a lot writers—no need to list them all here.) John Ashbery enjoyed a nice cup of tea and classical music when he wrote, which was usually in the late afternoon. Charles Simic enjoyed writing when his wife was cooking. Eudora Welty could write anywhere—even in the car— and at any time, except at night when she was socializing. Flannery O’Connor could only write two hours a day and her drink was Coca Cola mixed with coffee. Simone de Beauvoir wrote from 10AM-1PM and from 5-9PM. Louise Glück found writing on a schedule “an annihilating experience.” A. R. Ammons wrote only when inspiration hit—he compared trying to write to trying to force yourself to go the bathroom when you have no urge. Anne Sexton took up writing after therapy sessions. Jack Kerouac had various rituals at different times—one was writing by candlelight, and another was doing “touch downs” which involved standing on his head and touching his toes to the ground. Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf wrote standing up. Wallace Stevens composed poems while walking to work. Gabriel García Márquez listened to the news before writing. Amy Gerstler sometimes listens to recordings of rain while writing. I tried that once, and the rain put me into a deep and dreamless sleep.”

course, played an important role for a lot writers—no need to list them all here.) John Ashbery enjoyed a nice cup of tea and classical music when he wrote, which was usually in the late afternoon. Charles Simic enjoyed writing when his wife was cooking. Eudora Welty could write anywhere—even in the car— and at any time, except at night when she was socializing. Flannery O’Connor could only write two hours a day and her drink was Coca Cola mixed with coffee. Simone de Beauvoir wrote from 10AM-1PM and from 5-9PM. Louise Glück found writing on a schedule “an annihilating experience.” A. R. Ammons wrote only when inspiration hit—he compared trying to write to trying to force yourself to go the bathroom when you have no urge. Anne Sexton took up writing after therapy sessions. Jack Kerouac had various rituals at different times—one was writing by candlelight, and another was doing “touch downs” which involved standing on his head and touching his toes to the ground. Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf wrote standing up. Wallace Stevens composed poems while walking to work. Gabriel García Márquez listened to the news before writing. Amy Gerstler sometimes listens to recordings of rain while writing. I tried that once, and the rain put me into a deep and dreamless sleep.”

“In the small town of Eastwick, Rhode Island, three women — Alexandra, Jane, and Sukie — discover they have magical powers after their marriages end.

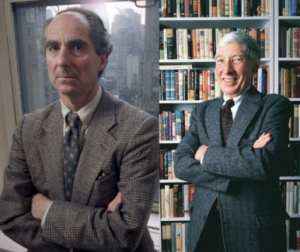

“In the small town of Eastwick, Rhode Island, three women — Alexandra, Jane, and Sukie — discover they have magical powers after their marriages end. On the American Literature public Facebook group, Milan Milan Stankovic posted a consideration/comparison of two “Great American Writers” whose works offer “profound insights into American society, culture, and individual psychological and individual psychological complexities”: John Updike and Philip Roth.

On the American Literature public Facebook group, Milan Milan Stankovic posted a consideration/comparison of two “Great American Writers” whose works offer “profound insights into American society, culture, and individual psychological and individual psychological complexities”: John Updike and Philip Roth. This National Windows Day (that’s a thing?), renowned photographer Jill Krementz shared some of the photos she took of

This National Windows Day (that’s a thing?), renowned photographer Jill Krementz shared some of the photos she took of