British novelist and short story writer William Boyd wrote a piece for The Spectator on a curious consequence of literary fame—mass booksignings—that began with an anecdote about John Updike:

Category Archives: Updike in Context

Updike’s American Everyman is referenced in a July 4 think piece

It’s July 4 in the U.S., and Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom is once again in the news—or rather, a think piece. Warning: Though Harry leaned right, The Nation, in which this piece by Jeet Heer appears, leans left. One statistic, though, seems more personal than political, because the comparison year (2004) is one during which another Republican president, George W. Bush, was in office:

Currently, “Only 58 percent of Americans say they are extremely proud or very proud of their country. (This is down from a high of 91 percent in 2004.) Among Democrats, this number stands at 38 percent, among independents at 53 percent. Among Gen Z Americans (born between 1997 and 2012), only 41 percent feel pride in their country.”

Heer had written, “Not too long ago, the Fourth of July was a festive occasion: a day of national celebration, hot dogs and parades, flag-waving and fireworks. John Updike memorialized the traditional July 4 holiday in Rabbit at Rest (1990), the final novel of his Rabbit trilogy. In that novel, Updike’s antihero, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, a former high school basketball star now in his paunchy and troubled late middle age, dresses up as Uncle Sam for a parade in his hometown of Brewer, Pennsylvania (a thinly disguised rendition of the real-life Reading). His fake beard uneasily held on by Scotch tape, Angstrom surveys the American throng gathered in patriotic jubilation:

Heer had written, “Not too long ago, the Fourth of July was a festive occasion: a day of national celebration, hot dogs and parades, flag-waving and fireworks. John Updike memorialized the traditional July 4 holiday in Rabbit at Rest (1990), the final novel of his Rabbit trilogy. In that novel, Updike’s antihero, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, a former high school basketball star now in his paunchy and troubled late middle age, dresses up as Uncle Sam for a parade in his hometown of Brewer, Pennsylvania (a thinly disguised rendition of the real-life Reading). His fake beard uneasily held on by Scotch tape, Angstrom surveys the American throng gathered in patriotic jubilation:

White-haired women sit in their aluminum lawn chairs down by the curb dressed like fat babies in checks and frills, their shapeless veined legs cheerfully protruding. Middle-aged men have squeezed their keglike thighs into bicycle shorts meant for boys. Young mothers have come from their back-yard aboveground swimming pools in bikinis and high-sided twists of spandex that leave half their buttocks and breasts exposed.

“Like Angstrom, the celebrants are imperfect and beset by their own private anxieties, but also beneficiaries of a country that has allowed them in some small way to enjoy the Jeffersonian promise of the pursuit of happiness. Exultant despite his physical diminishment, Angstrom has an epiphany: ‘Harry’s eyes burn and the impression giddily—as if he had been lifted up to survey all human history—grows upon him, making his heart thump worse and worse, that all in all this is the happiest fucking country the world has ever seen.”

Updike’s Rabbit makes a rise-of-suburbia list

Fritz Von Burkersroda posted on his site, Festivaltopia, a list of “19 Novels that captured the rise of the American suburb,” and John Updike’s 1960 novel Rabbit, Run was included.

“John Updike’s 1960 novel introduced readers to Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom, perhaps the most iconic character in suburban literature. Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom is a middle-class man who feels there is something missing from his life. The novel follows Rabbit as he flees his suburban responsibilities—his pregnant wife, his job, his entire life—in a desperate attempt to recapture the vitality of his youth. Frank Wheeler, Piet Hanema, Frank Bascombe – these are a handful of the suburban men in the fiction of Richard Yates, John Updike, and Richard Ford. These writers all display certain characteristics of the suburban novel in the post-WWII era: the male experience placed at the forefront of narration, the importance of competition both socially and economically, contrasting feelings of desire and loathing for predictability, and the impact of an increasingly developed landscape upon the American psyche and the individual’s mind. Updike’s genius was in making Rabbit both sympathetic and infuriating—a man whose suburban malaise drives him to make increasingly destructive choices. The novel launched a series that would span four decades, chronicling the evolution of suburban America through one man’s journey.”

“John Updike’s 1960 novel introduced readers to Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom, perhaps the most iconic character in suburban literature. Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom is a middle-class man who feels there is something missing from his life. The novel follows Rabbit as he flees his suburban responsibilities—his pregnant wife, his job, his entire life—in a desperate attempt to recapture the vitality of his youth. Frank Wheeler, Piet Hanema, Frank Bascombe – these are a handful of the suburban men in the fiction of Richard Yates, John Updike, and Richard Ford. These writers all display certain characteristics of the suburban novel in the post-WWII era: the male experience placed at the forefront of narration, the importance of competition both socially and economically, contrasting feelings of desire and loathing for predictability, and the impact of an increasingly developed landscape upon the American psyche and the individual’s mind. Updike’s genius was in making Rabbit both sympathetic and infuriating—a man whose suburban malaise drives him to make increasingly destructive choices. The novel launched a series that would span four decades, chronicling the evolution of suburban America through one man’s journey.”

Other titles that made the list include The Stepford Wives, Revolutionary Road, Little Children, The Ice Storm, The Corrections, Peyton Place, White Noise, Empire Falls, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, The Palisades, and John Cheever’s Collected Stories.

Killing time by chasing Updike

Every creative person has preferred ways of taking a break. For cartoonist Michael Maslin (“Wednesday Spill: Hunting for the Whereabouts of an Updike Moment”), one of those breaks began by looking at his Updike books and pulling one off the shelf. As it turns out, his diversion is the literary scholar’s method:

“Gearing up for the book of John Updike letters coming out in October I thought I’d once again travel through Adam Begley’s terrif Updike. Curiosity took me on a hunt when I came across this sentence on page 426:

“’A decade later, when he came across a well-thumbed copy of S in a small public library in the Hudson Valley, he remembered how he had put his “heart and soul” into the heroine and concluded that the novel had at last been “recognized”.’

“It was the ‘…small public library in the Hudson Valley…’ that sent me scampering to Google. As I live in the Hudson Valley and am acquainted with a number of its libraries, I figured I’d be able to (hopefully!) quickly zero in on which library Updike visited. Researching the Peter Arno biography i wrote, I quickly learned things just don’t go as smoothly as you might think when on a fact-finding mission.

“The ‘Notes’ in Begley’s Updike biography indicate the ‘…small public library…’ passage was sourced from Updike’s Odd Jobs, page 761. I headed right to Odd Jobs, page 761, but the passage wasn’t there. Dead end. It happens (my biography of Peter Arno has its share of ‘issues.’). I briefly considered writing Mr. Begley, but decided that this was too small a ‘thing’ for him to be troubled with. A day or two went by. I tried to let the hunt go. Then, this afternoon, having worked on cartoons for hours, and in need of a break, I sat next to the Updike section of our bookshelves and thought for a moment. What if the page number 761 was correct, but the book title was off. I began looking through Updike’s various hefty collections, beginning with Higher Gossip: zip. Due Considerations: zip. More Matter…bingo! There, on page 761 is this from Updike’s ‘Me and My Books’ — it was originally published in The New Yorker, February 3, 1997:

“‘On one steel shelf, in a Hudson Valley town with its own tributary creek gurgling over a dam and under a bridge near the library door…’

“I began thinking about the Hudson Valley libraries I was familiar with. None of them fit Updike’s description. So back to Google and to the list of libraries lining the Hudson Valley. Using Google maps (aerial view) I was able to easily see if any library was that close to water. I struck out with perhaps twenty or so libraries, when I saw this location in Marlboro, New York. And then using the street view, there it was, exactly as Updike described it: ‘tributary creek gurgling over a dam and under a bridge.’ This scene is directly across from the Gomez Mill House.

Was Updike partly responsible for Tim O’Brien’s literary ascent?

LitHub recently published a fascinating piece by Alex Vernon, “Bringing the War Home: How Tim O’Brien Approached the Art of Moral Consequence” (May 27, 2025), in which John Updike featured prominently.

The issue was negative versus positive reviews. Christopher Lehmann-Haupt’s New York Times review was cited as an example of the former, with Lehmann-Haupt arguing that “by repeatedly invoking Catch-22 Mr. O’Brien reminds us that Mr. Heller caught the madness of war better, if only because the logic of Catch-22 is consistently surrealistic and doesn’t try to mix in fantasies that depend on their believability to sustain. I can even imagine it being said that Going After Cacciato is the Catch-22 of Vietnam. The trouble is, Catch-22 is the Catch-22 of Vietnam.”

The issue was negative versus positive reviews. Christopher Lehmann-Haupt’s New York Times review was cited as an example of the former, with Lehmann-Haupt arguing that “by repeatedly invoking Catch-22 Mr. O’Brien reminds us that Mr. Heller caught the madness of war better, if only because the logic of Catch-22 is consistently surrealistic and doesn’t try to mix in fantasies that depend on their believability to sustain. I can even imagine it being said that Going After Cacciato is the Catch-22 of Vietnam. The trouble is, Catch-22 is the Catch-22 of Vietnam.”

Vernon wrote, “Not to worry, as The New York Times Book Review lauded the novel on its front page and didn’t cite Heller. It did bring in Hemingway, as did John Updike’s review in The New Yorker, which struck the opposite note as Lehmann-Haupt’s: ‘As a fictional portrait of this war, Going After Cacciato is hard to fault, and will be hard to better.’

“Cacciato enjoyed plenty of glowing reviews, yet Updike’s review had a huge impact on its success and helped convince the reading world to pay attention to the literature of O’Brien’s war. As O’Brien’s agent’s office wrote to Lawrence, “The John Updike review in The New Yorker seemed to be the word that tipped the scales against resistance to a Viet Nam novel, and now all the scouts are asking for it.”

Updike and Wallace seem forever linked in writing debates

In a June 9, 2025 piece published by The New Statesman, George Monaghan considered “The revenge of the young male novelist; Can good writing solve our crisis of masculinity?”

Of course, John Updike came up, and so did a writer once influenced by him who later seemed to make a bigger name for himself by attacking him: David Foster Wallace. The context: ego as it relates to writers.

“American novelist John Updike claimed not to write for ego: ‘I think of it more as innocence. A writer must be in some way innocent.’ We might raise an eyebrow at this, from the highly successful and famously intrusive chronicler of human closeness. Even David Foster Wallace, the totem effigy of literary chauvinism, denounced Updike as a ‘phallocrat.’ But if we doubt such innocence of Updike, pronouncing as he was at the flushest height of fiction’s postwar heyday, we might believe it of these new novelists, writing as they are and when they are. Without a promise of glory, and facing general skepticism, they have written from pure motives. They are novelists as Updike defined them: ‘only a reader who was so excited that he tried to imitate and give back the bliss that he enjoyed’.

“American novelist John Updike claimed not to write for ego: ‘I think of it more as innocence. A writer must be in some way innocent.’ We might raise an eyebrow at this, from the highly successful and famously intrusive chronicler of human closeness. Even David Foster Wallace, the totem effigy of literary chauvinism, denounced Updike as a ‘phallocrat.’ But if we doubt such innocence of Updike, pronouncing as he was at the flushest height of fiction’s postwar heyday, we might believe it of these new novelists, writing as they are and when they are. Without a promise of glory, and facing general skepticism, they have written from pure motives. They are novelists as Updike defined them: ‘only a reader who was so excited that he tried to imitate and give back the bliss that he enjoyed’.

“So it may be no bad thing if none of these novels quite fetches the reviews Wallace’s masterpiece Infinite Jest did (‘the plaques and citations can now be put in escrow. … it’s as though Wittgenstein has gone on Jeopardy!’). These guys want to start a moment, not end one. They more want to write novels than be novelists. It is hard to say what relief these books might bring to a societal masculinity crisis, but in composing them their authors have displayed at least the two simple virtues Updike wanted to claim for himself: ‘a love of what is, and a wish to make a thing.'”

About John John Updike’s Writing Routine

There’s a website for everything these days, including one on Famous Writing Routines. What works for one writer might not work for another, but when that one writer is John Updike, who wrote more than 60 books during his professional lifetime, there has to be something, even in a single tip—which is what these posts seem to entail—to help writers aspiring to complete ONE book. Hao Nguyen shared this writing advice from Updike:

“Even though you have a busy life, try to reserve an hour a day to write. Some very good things have been written on an hour a day.”

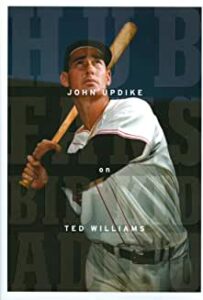

‘New Yorker’ celebrates Ted Williams (and John Updike)

As part of a grand centennial year celebration, an episode of The New Yorker Radio Hour featured “Louisa Thomas on a Ballplayer’s Epic Final Game,” a remembrance that “naturally gravitated to a story about baseball with a title only comprehensible to baseball aficionados: “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.” The essay was by no less a writer than the author John Updike, and the “Kid” of the title was Ted Williams, the Hall of Fame hitter who spent nineteen years on the Boston Red Sox. By happenstance, Updike joined the crowd at Fenway Park for Williams’s last game before his retirement, in 1960. Thomas, looking at subtle word changes that Updike made as he was working on the piece, reflects on the writer’s craft and the ballplayer’s. ‘Marginal differences really matter,’ she says. ‘And it’s those marginal differences that are the difference between a pop-up, a long fly, and a home run. Updike really understood that, and so did Williams.’

As part of a grand centennial year celebration, an episode of The New Yorker Radio Hour featured “Louisa Thomas on a Ballplayer’s Epic Final Game,” a remembrance that “naturally gravitated to a story about baseball with a title only comprehensible to baseball aficionados: “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.” The essay was by no less a writer than the author John Updike, and the “Kid” of the title was Ted Williams, the Hall of Fame hitter who spent nineteen years on the Boston Red Sox. By happenstance, Updike joined the crowd at Fenway Park for Williams’s last game before his retirement, in 1960. Thomas, looking at subtle word changes that Updike made as he was working on the piece, reflects on the writer’s craft and the ballplayer’s. ‘Marginal differences really matter,’ she says. ‘And it’s those marginal differences that are the difference between a pop-up, a long fly, and a home run. Updike really understood that, and so did Williams.’

Excerpts from ‘Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,’ by John Updike, were read by Brian Morabito.”

Updike’s former Boston condo lists for sale

For a short time, Updike left suburbia for Boston’s Back Bay, living in one of the units at 151 Beacon Street—#4. Now that unit can be yours for $2.85 million. From BostonRealEstate.com:

“Welcome to a distinguished residence where historic charm meets modern comfort. Spanning 2 grand Back Bay townhouses, this home offers city living at its finest. Originally built for the Lowell family & later home to John Updike, 151 Beacon features 3 bedrooms, 2.5 baths, & over 2,000 sq. ft. of sophisticated living space. Enjoy direct elevator access, a formal living room w/ gas fireplace, custom built-ins, & oversized windows framing picturesque Beacon Street views. The open-concept kitchen, enhanced by bay windows w/ striking John Hancock Tower views, boasts a central island & a second gas fireplace. The primary suite offers a luxurious retreat w/ an oversized walk-in closet & spacious ensuite bath. 2 additional bedrooms, a powder room, in-unit laundry, & two separate AC/heat units complete the layout. Set in a professionally managed, boutique building of just 6 residences, this home includes 1 tandem parking space & is around the corner from some of Bostons Historic landmarks.”

“Welcome to a distinguished residence where historic charm meets modern comfort. Spanning 2 grand Back Bay townhouses, this home offers city living at its finest. Originally built for the Lowell family & later home to John Updike, 151 Beacon features 3 bedrooms, 2.5 baths, & over 2,000 sq. ft. of sophisticated living space. Enjoy direct elevator access, a formal living room w/ gas fireplace, custom built-ins, & oversized windows framing picturesque Beacon Street views. The open-concept kitchen, enhanced by bay windows w/ striking John Hancock Tower views, boasts a central island & a second gas fireplace. The primary suite offers a luxurious retreat w/ an oversized walk-in closet & spacious ensuite bath. 2 additional bedrooms, a powder room, in-unit laundry, & two separate AC/heat units complete the layout. Set in a professionally managed, boutique building of just 6 residences, this home includes 1 tandem parking space & is around the corner from some of Bostons Historic landmarks.”

Updike mentioned in review of Diana Evans essay collection

British writer Diana Evans has written four acclaimed novels and, more recently, a collection of essays titled I Want to Talk to You and Other Conversations. In Alex Clark’s review of the book, John Updike surfaces as an influence:

British writer Diana Evans has written four acclaimed novels and, more recently, a collection of essays titled I Want to Talk to You and Other Conversations. In Alex Clark’s review of the book, John Updike surfaces as an influence:

“Thinking about Rhys and her peripatetic, rackety life leads Evans to interrogate the ways in which writers of fiction might reach their own particular method of ‘psychological enunciation.’ It’s a delicious counterpoint to Evans’s fondness for John Updike; crediting his novel Couples with influencing Ordinary People, she describes what might legitimately be called a guilty pleasure, weighing the erasing masculinity of his work against the sentences ‘like hot-air balloons drifting through a dazzling harlequin sky.’ It was also being alive to the domestic ease of the married protagonists of Couples that sparked Evans to ask: ‘How often do middle-class black people in books get to just live in their damn houses and open and close their wardrobes and be aware of each other’s fingertips?'”