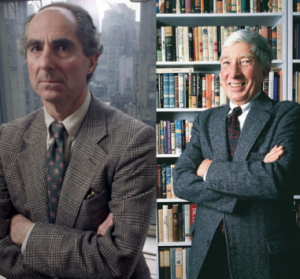

Frank T. Pool (Longview News-Journal)recently quoted Emily Dickinson (“There is no Frigate like a Book / To take us Lands away”) and referenced John Updike, who “once said that he had read all of Dickens except for one novel, Our Mutual Friend, which he was saving for some time in his life he really needed it.”

As David McGrath of the Naperville Sun observed, “If there’s one benefit to self-quarantining and sheltering in place, it’s the gift of time you now have to read”—and McGrath and a number of readers are reading, rediscovering, and recommending Updike.

McGrath has three criteria for picking a solitary confinement book to read: ” 1) The book is pleasurable to read. 2) The book is a long-lasting self investment. 3) The book is a prize winner, but one we probably have yet to read.” Updike heads McGrath’s list of top 10 recommendations for reading in the time of Covid-19—specifically, Updike’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Rabbit Is Rich, which McGrath calls “one of the titles you might not have read by the American novelist, who should have won the Nobel Prize in any single year from 1981 to 2008. That’s 27 times that the Nobel committee blew it.”

McGrath has three criteria for picking a solitary confinement book to read: ” 1) The book is pleasurable to read. 2) The book is a long-lasting self investment. 3) The book is a prize winner, but one we probably have yet to read.” Updike heads McGrath’s list of top 10 recommendations for reading in the time of Covid-19—specifically, Updike’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Rabbit Is Rich, which McGrath calls “one of the titles you might not have read by the American novelist, who should have won the Nobel Prize in any single year from 1981 to 2008. That’s 27 times that the Nobel committee blew it.”

For British Vogue editor Rachel Garrahan (“The Vogue Editors’ Favourite Books of All Time”), the series she’s “looking forward to rereading is John Updike’s Rabbit books. Against a backdrop of massive social, political, and economic change in post-war America, it follows Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom through the ups and downs of what David Baddiel once described as his ‘beautifully mundane’ life. Rabbit is a perfectly imperfect protagonist who makes you laugh, cry and scream at him in frustration. It will be good to do those things to someone other than my husband and children over the coming weeks.”

Meanwhile, satirist Craig Brown, himself the author of 18 books, told The Guardian that the writer he returns to most often is John Updike, who is “pretty reliable.”

Meanwhile, satirist Craig Brown, himself the author of 18 books, told The Guardian that the writer he returns to most often is John Updike, who is “pretty reliable.”

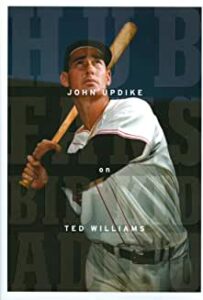

And more recently, The Washington Post staff included Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu as one of “The best sports books to read now” in this time of self-isolation:

Micah Pollack writes, “Less a sports book and more a sports essay, Updike’s 1960 New Yorker chronicle of Ted Williams’s final game as a player lives on nearly 60 years later as a towering piece of sportswriting. Lyrical, mystical and with a fluidity to match the Splinter’s swing, it has been reprinted countless times, but the 50-year anniversary that came out in hardcover 10 years ago is worth the time and the change. It includes a great afterward from the author on his fascination with Williams, and both the inside cover and back cover pull the curtain back on some of Updike’s own self-editing, a nice touch. Updike dabbled in sports in his Rabbit series (those novels’ central figure is a former high school basketball star), but this was his only true foray into sportswriting. He was one of 10,454 at Fenway Park on that chilly, overcast September day. He stayed to watch Williams homer in his final at-bat. Then he left to write about it. He retired as a sportswriter, undefeated.”

The Star Tribune‘s longtime baseball reporter and current college sports editor Joe Christensen also included Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu in his “Suggested sports books, from the Star Tribune Staff” recommendations: “John Updike and a few thousand Bostonians turned out to witness what would be Ted Williams’ final baseball game. That he hit a home run in his last at-bat and refused to tip his cap to a roaring crowd, provides the germ for the best sports profile ever written.”