On Sept. 4, 2023, Philadelphia-based cultural reporter and critic Julia Klein’s review of The John Updike Childhood Home was published in The Wall Street Journal. Klein, an expert on museums, spent three hours walking through the house and taking notes on the 10 rooms of exhibits.

“For such a clear-eyed chronicler of America’s angst-ridden middle class, John Updike was surprisingly sentimental about his Pennsylvania roots. Here, one of his narrators declared, ‘the basic treasure of his life was buried,’” Klein wrote.

“In the short story ‘The Brown Chest,’ Updike’s narrator recalls ‘the house that he inhabited as if he would never live in any other’ and the ‘strange, and ancient, and almost frightening’ wooden chest that served as a repository of family memories.

“Both its hold on the author and the allure of its intimate artifacts, from that chest to Updike’s earliest drawings, make the John Updike Childhood Home a worthy site of literary pilgrimage.

“Both its hold on the author and the allure of its intimate artifacts, from that chest to Updike’s earliest drawings, make the John Updike Childhood Home a worthy site of literary pilgrimage.

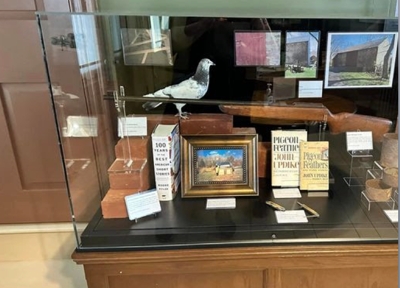

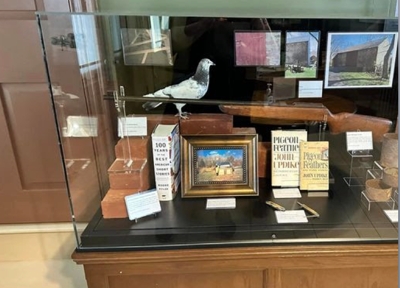

“The house museum, opened in October 2021, recently added seven vitrines, with artifacts including the Remington rifle of Updike’s short story ‘Pigeon Feathers’ and the Olivetti manual typewriter he used for four decades.”

The John Updike Society purchased The John Updike Childhood Home in 2012 with the intent of turning it into a literary site and museum to celebrate one of America’s greatest writers. The purchase was made possible by a grant from The Robert and Adele Schiff Family Foundation, which also supported every year of the meticulous restoration so that the house would look, inside and out, as it did during Updike’s time there. That foundation and others—most notably The PECO Foundation and The John and Gaye Patton Charitable Foundation—enabled the society to complete work and acquire many exhibits, while Elizabeth Updike Cobblah, David Updike, Michael Updike, and Miranda Updike contributed a great many family treasures. But donations also came from society members, Updike’s childhood friends, and members of the community who have embraced the museum as their own.

“Curated by James Plath, an Illinois Wesleyan University professor and president of the Updike Society, the museum celebrates Updike’s career, emphasizing how Shillington formed him as a writer,” Klein wrote, adding that the museum’s thematic approach “pays off particularly well in his mother’s writing room,” where images and artifacts suggest the complicated mother-son relationship with each other and their shared goal of becoming a writer. “The relationship seems to have been at once close and embattled, with the son vaulting to the literary success his mother craved.”

Updike Society members can be proud that the nine-year project has been positively received. It’s been a long journey that began with Habitat for Humanity of Berks County volunteers stripping wallpaper and tile flooring and knocking out walls that had been added after the Updikes moved out. Then restoration expert Bob Doerr and his crew carefully researched the details of the house during Updike’s time and restored it so meticulously that an older couple who had visited the house when the Updikes lived there said it was just as they remembered it.

Updike Society members can be proud that the nine-year project has been positively received. It’s been a long journey that began with Habitat for Humanity of Berks County volunteers stripping wallpaper and tile flooring and knocking out walls that had been added after the Updikes moved out. Then restoration expert Bob Doerr and his crew carefully researched the details of the house during Updike’s time and restored it so meticulously that an older couple who had visited the house when the Updikes lived there said it was just as they remembered it.

Society community members donated Updike and Shillington artifacts and books, while Dave Silcox helped to find local treasures for the museum. John Updike Childhood Home director Maria Lester, and before her Sue Guay, worked with Plath to move the project forward, while property manager John Trimble arranged all of the objects that had been selected for display in cases and took care of printing all the IDs that were provided and hanging all of the wall art and artifacts. And more than a dozen docents, Dave Ruoff the most senior among them, volunteered their time to staff the museum. Many more people were involved, of course—too many to name—because it truly takes a borough to create and sustain a museum like this.

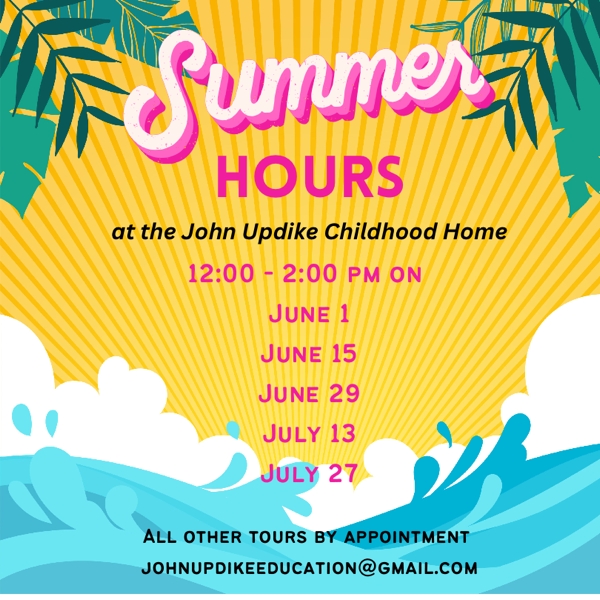

If you would like to become involved in the Updike society, email jplath@iwu.edu; if you live in the area and would like to volunteer as a docent, contact Maria Lester, johnupdikeeducation@gmail.com.

Maria Lester, director of The John Updike Childhood Home that is owned and operated by the 501c3 John Updike Society, received word recently that the museum at 117 Philadelphia Ave. in Shillington, Pa. was awarded a $25,000 Chairman’s Grant from the head of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Maria Lester, director of The John Updike Childhood Home that is owned and operated by the 501c3 John Updike Society, received word recently that the museum at 117 Philadelphia Ave. in Shillington, Pa. was awarded a $25,000 Chairman’s Grant from the head of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

“At the greengrocer’s on Monday morning they purchased still life ingredients. The Constable School owned a great bin of inanimate objects, from which Leonard had selected an old mortar and pestle. His idea was then to buy, to make a logical picture, some vegetables that could be ground, and to arrange them in a Chardinesque tumble. But what, really, was ground, except nuts? The grocer did have some Jamaican walnuts.

“At the greengrocer’s on Monday morning they purchased still life ingredients. The Constable School owned a great bin of inanimate objects, from which Leonard had selected an old mortar and pestle. His idea was then to buy, to make a logical picture, some vegetables that could be ground, and to arrange them in a Chardinesque tumble. But what, really, was ground, except nuts? The grocer did have some Jamaican walnuts.

Not everyone who recognizes themselves in a writer’s fiction or poetry is pleased, but William Ecenbarger took delight in recalling his 1983 interview with John Updike that inspired Updike to write “One More Interview.” Then a writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Ecenbarger managed to score his interview with Updike through the writer’s mother, Linda. It was no ordinary interview.

Not everyone who recognizes themselves in a writer’s fiction or poetry is pleased, but William Ecenbarger took delight in recalling his 1983 interview with John Updike that inspired Updike to write “One More Interview.” Then a writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Ecenbarger managed to score his interview with Updike through the writer’s mother, Linda. It was no ordinary interview.