On Feb. 1, 2026, Martin Wenglinsky, an Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Quinnipiac University, posted on his blog the first of his two-part examination of John Updike’s futuristic novel, Toward the End of Time, which he called a “deficient” or “deformed” epic.

“Let me explain,” Wenglinsky wrote. “An epic is a story of war and family and a journey and one or more heroic protagonists and what might be endlessly elaborated episodes that convey some deep meaning about human nature, while novels, which are another kind of deformed epics, have protagonists whose histories are never retold but made up and just trying to manage life.”

In Toward the End of Time, Wenglinsky wrote, “The war envisioned is a limited exchange of atomic weapons between China and the United States that takes place a few decades in the future of the time the novel was published. The people in the novel are civilians trying to cope with the aftermath, which makes sense because the war that engulfed the world in the second half of the twentieth century was the Cold War, which had hot skirmishes in Korea and Vietnam and the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan, but unlike in other wars mostly in prospect, a full out exchange never happening even if many predicted it, imaginations filled with the nuclear apocalypse just thirty minutes away from total mutual destruction. So this war is a science fiction war, and Updike’s innovation is that there is a limited exchange so that the United States has had severe but not total annihilation, which is different from apocalyptic science fiction projections as happens in Shute’s On the Beach (1957), or Christopher’s No Blade of Glass (1956) or Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids (1951) or to my mind the most scary documentary style BBC production, Mick Jackson’s Threads (1984)) which showed the reduction of England to a medieval economy and society. Rather, the United States, in Updike’s imagination, remains organized even if diminished and it is unclear whether it will recover or fall into anarchy.

In Toward the End of Time, Wenglinsky wrote, “The war envisioned is a limited exchange of atomic weapons between China and the United States that takes place a few decades in the future of the time the novel was published. The people in the novel are civilians trying to cope with the aftermath, which makes sense because the war that engulfed the world in the second half of the twentieth century was the Cold War, which had hot skirmishes in Korea and Vietnam and the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan, but unlike in other wars mostly in prospect, a full out exchange never happening even if many predicted it, imaginations filled with the nuclear apocalypse just thirty minutes away from total mutual destruction. So this war is a science fiction war, and Updike’s innovation is that there is a limited exchange so that the United States has had severe but not total annihilation, which is different from apocalyptic science fiction projections as happens in Shute’s On the Beach (1957), or Christopher’s No Blade of Glass (1956) or Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids (1951) or to my mind the most scary documentary style BBC production, Mick Jackson’s Threads (1984)) which showed the reduction of England to a medieval economy and society. Rather, the United States, in Updike’s imagination, remains organized even if diminished and it is unclear whether it will recover or fall into anarchy.

“Updike’s novel is no reduction of a society into Hobbesian anarchy. Seafood is shipped from the East Coast to the decimated Midwest. Commerce also continues in that protection rackets spring up and young women openly advertise their personal services in the major newspapers and a local scrip has replaced the United States dollar but there are still country clubs and Federal Express and mail service and a diminished food market in some stands around downtown Boston. What Updike retains from the apocalyptic genre, which is only somewhere in the epic mode, as is the case with “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” (c. 1400), which is full of foreboding about what will be the fatal mistake of the hero, is a sense of dread and despair: that something even worse will happen and that the eventual fate cannot be avoided however people battle on to restore what was once normal life. Achieving that tone in a less than complete apocalypse is a considerable achievement for Updike.

“But there is much more going on than that,” Wenglinsky wrote.

Read Part 1 of his essay, “John Updike: Toward the End of Time“

The issue was negative versus positive reviews. Christopher Lehmann-Haupt’s New York Times review was cited as an example of the former, with Lehmann-Haupt arguing that “by repeatedly invoking Catch-22 Mr. O’Brien reminds us that Mr. Heller caught the madness of war better, if only because the logic of Catch-22 is consistently surrealistic and doesn’t try to mix in fantasies that depend on their believability to sustain. I can even imagine it being said that

The issue was negative versus positive reviews. Christopher Lehmann-Haupt’s New York Times review was cited as an example of the former, with Lehmann-Haupt arguing that “by repeatedly invoking Catch-22 Mr. O’Brien reminds us that Mr. Heller caught the madness of war better, if only because the logic of Catch-22 is consistently surrealistic and doesn’t try to mix in fantasies that depend on their believability to sustain. I can even imagine it being said that  “There are thus good arguments for the premise of John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius that Hamlet’s father is the truly evil person in the play, and that his injunction to Hamlet is an obscenity. Updike’s novel is a prequel to Shakespeare’s play: Gertrude and Claudius are engaged in an adulterous affair (Shakespeare is ambiguous on this point), and this affair is presented as passionate true love. Gertrude is a sensual, somewhat neglected wife, Claudius a rather dashing fellow, and old Hamlet an unpleasant combination of brutal Viking raider and coldly ambitious politician. Claudius has to kill the old Hamlet because he learns that the old king plans to kill them both (and he does it without Gertrude’s knowledge or encouragement). Claudius turns out to be a good, generous king; he lives and reigns happily with Gertrude, and everything runs smoothly until Hamlet returns from Wittenberg and throws everything out of joint. Whatever we imagine as the (fictional) reality of Hamlet, Gertrude is the only kindhearted and basically honest person in the play.”

“There are thus good arguments for the premise of John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius that Hamlet’s father is the truly evil person in the play, and that his injunction to Hamlet is an obscenity. Updike’s novel is a prequel to Shakespeare’s play: Gertrude and Claudius are engaged in an adulterous affair (Shakespeare is ambiguous on this point), and this affair is presented as passionate true love. Gertrude is a sensual, somewhat neglected wife, Claudius a rather dashing fellow, and old Hamlet an unpleasant combination of brutal Viking raider and coldly ambitious politician. Claudius has to kill the old Hamlet because he learns that the old king plans to kill them both (and he does it without Gertrude’s knowledge or encouragement). Claudius turns out to be a good, generous king; he lives and reigns happily with Gertrude, and everything runs smoothly until Hamlet returns from Wittenberg and throws everything out of joint. Whatever we imagine as the (fictional) reality of Hamlet, Gertrude is the only kindhearted and basically honest person in the play.”

Chase Replogle, pastor of Bent Oak Church in Springfield, Mo., posted a chapter excerpt that didn’t make the final cut of his book, A Sharp Compassion. “I think it still matters, he wrote. “It is taken from the chapter on affirmation and examines how the church has been tempted to avoid what offends.”

Chase Replogle, pastor of Bent Oak Church in Springfield, Mo., posted a chapter excerpt that didn’t make the final cut of his book, A Sharp Compassion. “I think it still matters, he wrote. “It is taken from the chapter on affirmation and examines how the church has been tempted to avoid what offends.” In

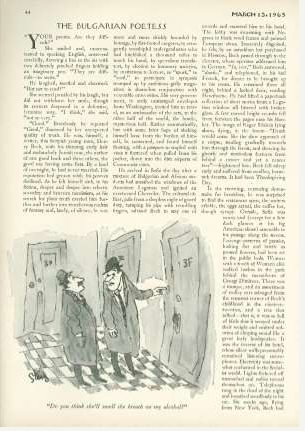

In  ABSTRACT: This article provides an innovative perspective on John Updike’s visit to Eastern Europe in the 1960s, including Bulgaria, as reflected in his short story “The Bulgarian Poetess” first published in The New Yorker on March 13, 1965. The inspiration for this interpretation is as much academic as it is anthropological. It comes from Updike’s use of my own surname, Glavanakova, which is not a common Slavic one, for the fictional character of the real-life Bulgarian poetess he met, whom researchers have established to be Blaga Dimitrova. Many have delved into the text aiming at a detailed and, more significantly, an authentic reconstruction of events, places and people appearing in the story (Katsarova 2010; Kosturkov 2012; Briggs and Dojčinović 2015). A main preoccupation of these analyses has been to establish the degree of factual distortion in Updike’s representation of the people and places behind the Iron Curtain. The pervasive imagery of the mirror, implying both its reflecting and doubling function, and the repetitive use of cognates associated with truth and honesty in the story suggest the focus of this article, which falls on the dynamics between authenticity and artifice from the perspective of autofiction by way of illustrating how one culture translates into another “at the opposite side[s] of the world” (Updike, “The Bulgarian Poetess”). In my interpretation, autofiction opens ample spaces for representations and discussions of identity and self-/reflexivity in a transcultural context.

ABSTRACT: This article provides an innovative perspective on John Updike’s visit to Eastern Europe in the 1960s, including Bulgaria, as reflected in his short story “The Bulgarian Poetess” first published in The New Yorker on March 13, 1965. The inspiration for this interpretation is as much academic as it is anthropological. It comes from Updike’s use of my own surname, Glavanakova, which is not a common Slavic one, for the fictional character of the real-life Bulgarian poetess he met, whom researchers have established to be Blaga Dimitrova. Many have delved into the text aiming at a detailed and, more significantly, an authentic reconstruction of events, places and people appearing in the story (Katsarova 2010; Kosturkov 2012; Briggs and Dojčinović 2015). A main preoccupation of these analyses has been to establish the degree of factual distortion in Updike’s representation of the people and places behind the Iron Curtain. The pervasive imagery of the mirror, implying both its reflecting and doubling function, and the repetitive use of cognates associated with truth and honesty in the story suggest the focus of this article, which falls on the dynamics between authenticity and artifice from the perspective of autofiction by way of illustrating how one culture translates into another “at the opposite side[s] of the world” (Updike, “The Bulgarian Poetess”). In my interpretation, autofiction opens ample spaces for representations and discussions of identity and self-/reflexivity in a transcultural context.