In 1963, a 16 year old was tired of hearing about symbolism from his English teacher, wondering, as many students still do, if teachers read too much into a literary work. So he mailed a four-question survey to 150 novelists asking them about symbolism in their work. Exactly half of them responded, among them John Updike. Had young Bruce McAllister sent that survey just three years earlier, he could have included Ernest Hemingway, who famously once remarked, “All symbolism is shit.”

Specifically, McAllister wanted their opinion of symbolism in The Scarlet Letter, which his class was reading, but some of the responses were more general . . . and eye-opening.

MacKinlay Kantor (Andersonville, Gettysburg) was the most blunt: “Nonsense, young man, write your own research paper. Don’t expect others to do the work for you.

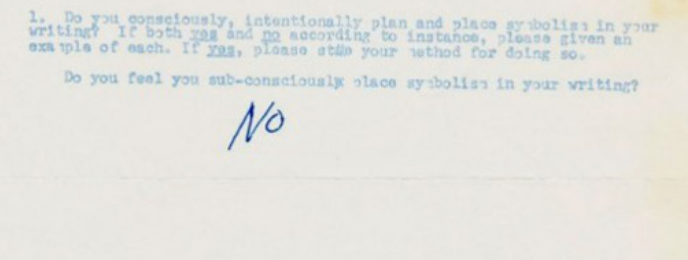

Jack Kerouac offered the briefest response to the question of placing symbolism in his work. “No,” Kerouac wrote back.

“Consciously?” Isaac Asimov responded. “Heavens, no! Unconsciously? How can one avoid it?”

Normal Mailer defined the best symbols as “those you become aware of only after you finish the work,” while Ralph Ellison seemed more reflective and representative of the writer’s method: “Symbolism arises out of action. . . . Once a writer is conscious of the implicit symbolism which arises in the course of a narrative, he may take advantage of them and manipulate them consciously as a further resource of his art.”

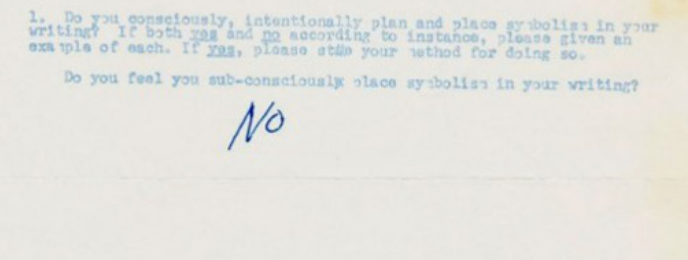

John Updike, meanwhile, spoke along the lines of writer-as-mystic, answering “Yes” to the question of whether he consciously, intentionally places symbolism in his writing, adding, “I have no method; there is no method in writing fiction; you don’t seem to understand.”

To the question of whether readers ever infer what is not intended, Updike responded, “Once in a while—usually they do not (see the) symbols that are there.”

Asked if he feels the great writers of classics consciously put symbols in their works, Updike wrote, “Some of them did (Joyce, Dante) more than others (Homer) but it is impossible to think of any significant work of narrative art without a symbolic dimension of some sort.”

As for the last question, whether he has anything to add that’s pertinent to a study of symbols, Updike sounded like Kantor: “It would be better for you to do your own thinking on this sort of thing.”

Read the full Mental Floss article.