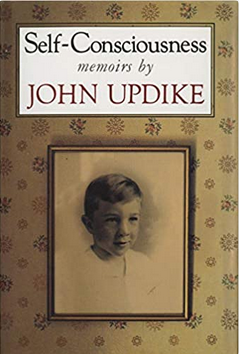

A guest columnist for the Daily Post Athenian [Tenn.] was inspired by Updike’s essay “Letter to a Baby Boomer” to write “a similar epistle to my former students, who now range between the ages of 30 and 45.”

Stephen W. Dick, a teacher at Athens Junior High School from 1989-2005 and a baby boomer himself, wrote that in Updike’s “Letter to a Baby Boomer” [re: those born between 1946-1964], “Mr. Updike, born in 1932 and writing to the generation following his own, simultaneously challenges and reassures us. Of course, addressing any generation in its entirety involves significant generalization, but thinking of us baby boomers, I believe we could largely agree on how we are perceived, even if individually we don’t fit those perceptions.”

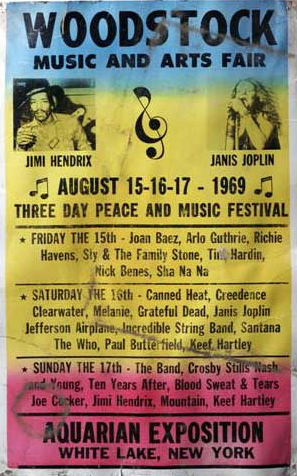

“According to Mr. Updike, we baby boomers, in our youth, ‘went to Woodstock, experienced altered states of consciousness, protested Vietnam, fought in it, or both.’

“In our adulthood, he writes that we ‘invented yuppieness, health consciousness, and corporate greed.’

“That stings, especially the last. Time always erodes youthful idealism, but my generation didn’t give it time to erode. We abruptly abandoned it, citing spouses and/or children as rationales, as if the future we once imagined couldn’t include families,” Dick wrote.

“In his conclusion to ‘Letter to a Baby Boomer,’ Updike quotes Shakespeare’s Prospero who, upon retiring, feared that ‘Every third thought shall be my grave.’

“Updike suggests the first two thoughts should be these: (1) Love one another, and (2) Seize the day. Those, I think, are beyond amendment.”