First U.K. Edition

The “about” tab says it all: “The concept of Colin’s Review is pretty self-explanatory. My name is Colin, and I review things. So, why should you care? Professional criticism is a dying industry. Ask any journalist or newspaper staff-writer and they’ll unfortunately tell you the same thing. However, there still exists a large contingency of readers who long for the golden era when criticism itself was just as artful as the topics the authors were reviewing. That’s what I strive to provide on this blog.”

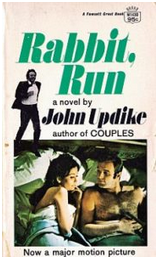

So far he’s only reviewed four books (and Updike might be cringing somewhere to discover that Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater merited an A while Rabbit, Run was awarded an A-), but Colin seems insightful, somewhat bold, and quite readable. In his review, after summarizing Updike’s first Rabbit novel in two sentences, Colin writes,

“It makes for a very funny premise, and when told through Updike’s extremely poetic and occasionally profound style, it makes for a very compelling read. After all, the masculine urge for escape is relatable to everyone. Or, rather, Updike’s such a talented writer that Rabbit’s masculine impulses are easy to empathize with. The further he self-destructs, the more human he becomes.

“Then again, Rabbit isn’t exactly the most likable protagonist . . . . Watching him constantly take advantage of those around him would be quite exhausting if it wasn’t for Updike’s wit and clarity. Not to mention the book’s present tense P.O.V., which keeps Rabbit’s cycle of assholery refreshing despite its repetition—an uncomfortable and entertaining read.

“Back in 1960, Rabbit, Run provided a fresh perspective: a window into the soul of American men disillusioned with the middle-class WASP lifestyle, searching for spirituality but lacking religion, obsessed with sex yet scared of commitment, desperate for meaning in a seemingly meaningless world. Admirable cowards, self-righteous fools.”

Colin notes that Updike had such an “immense” influence that “thousands of similar characters” have “taken up Rabbit’s running-away-from-family mantle. From American Pastoral to Cosmopolis to Five Easy Pieces, there’s no shortage of problematic white male protagonists. Then again, I can’t blame Updike for a half-century of imitators.”

The brisk review is made even brisker with sections on “Further Reading,” “Stray Observations (including Spoilers),” and “Quotes from Rabbit, Run.”

Read the full review

British writer Diana Evans has written four acclaimed novels and, more recently, a collection of essays titled I Want to Talk to You and Other Conversations. In Alex Clark’s review of the book, John Updike surfaces as an influence:

British writer Diana Evans has written four acclaimed novels and, more recently, a collection of essays titled I Want to Talk to You and Other Conversations. In Alex Clark’s review of the book, John Updike surfaces as an influence:

For this entry we need to thank writer

For this entry we need to thank writer

“The third installment of John Updike’s ‘Rabbit’ series finds Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom finally comfortable—or at least financially secure—amid the tumultuous backdrop of 1979’s oil crisis and stagflation. ‘How can you respect the world when you see it’s being run by a bunch of kids turned old?’ the narrator observes, capturing the novel’s eerie contemporary resonance: interest rates and real-estate climbing skyward—and staying there—and a gnawing certainty that the next generation won’t have it quite so good. Updike’s prose transforms the mundane rhythms of middle-class life into something approaching poetry as he excavates middle-class anxiety and success. Rabbit’s car dealership is printing money thanks to the Japanese vehicles he sells, even as his own prejudices and racial anxieties bubble beneath the surface. His son Nelson is adrift, the world seems to be coming apart at the seams and Rabbit’s own biases reflect the tensions of a changing America. The novel won Updike both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for its devastating precision in capturing what it means to ‘make it’ while watching the ladder get pulled up behind you.”

“The third installment of John Updike’s ‘Rabbit’ series finds Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom finally comfortable—or at least financially secure—amid the tumultuous backdrop of 1979’s oil crisis and stagflation. ‘How can you respect the world when you see it’s being run by a bunch of kids turned old?’ the narrator observes, capturing the novel’s eerie contemporary resonance: interest rates and real-estate climbing skyward—and staying there—and a gnawing certainty that the next generation won’t have it quite so good. Updike’s prose transforms the mundane rhythms of middle-class life into something approaching poetry as he excavates middle-class anxiety and success. Rabbit’s car dealership is printing money thanks to the Japanese vehicles he sells, even as his own prejudices and racial anxieties bubble beneath the surface. His son Nelson is adrift, the world seems to be coming apart at the seams and Rabbit’s own biases reflect the tensions of a changing America. The novel won Updike both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for its devastating precision in capturing what it means to ‘make it’ while watching the ladder get pulled up behind you.” Thomas wrote, “On a dreary Wednesday in September, 1960, John Updike, ‘falling in love, away from marriage,’ took a taxi to see his paramour. But, he later wrote, she didn’t answer his knock, and so he went to a ballgame at Fenway Park for his last chance to see the Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, who was about to retire. For a few dollars, he got a seat behind third base.

Thomas wrote, “On a dreary Wednesday in September, 1960, John Updike, ‘falling in love, away from marriage,’ took a taxi to see his paramour. But, he later wrote, she didn’t answer his knock, and so he went to a ballgame at Fenway Park for his last chance to see the Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, who was about to retire. For a few dollars, he got a seat behind third base. In an

In an

Today’s Washington Post featured a Q&A, “Post critic Michael Dirda turns a page: Dirda discusses the life of a critic, and his decision for a change of pace after 30 years of weekly columns,” in which John Updike merited a brief mention.

Today’s Washington Post featured a Q&A, “Post critic Michael Dirda turns a page: Dirda discusses the life of a critic, and his decision for a change of pace after 30 years of weekly columns,” in which John Updike merited a brief mention.