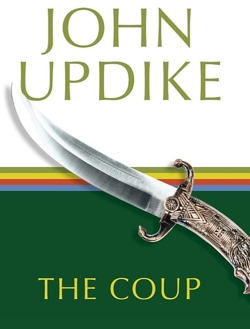

An “Alternative Media” site recently ran an opinion piece masquerading as news (“The Coming White Flight in Europe”) that quotes a big chunk of John Updike’s satirical 1978 novel, The Coup.

“Since the future of the world will be heavily influenced by the huge number of Sahelians headed our way, here’s the opening of John Updike’s 1978 novel The Coup, in which he describes a fictionalized Sahelian country much like Niger. Keep in mind, however, that the population of Niger in 1978 was 5.7 million. Today it is 21.5 million. In another 39 years, the span of time since Updike’s novel, it is expected to grow to 81.4 million. The Coup begins with the Col. Gadaffi-like Col. Ellellou writing his memoirs in a Nabokovian-Updikean prose style:

“‘My country of Kush, landlocked between the mongrelized, neo-capitalist puppet states of Zanj and Sahel, is small for Africa, though larger than any two nations of Europe. Its northern half is Saharan; in the south, forming the one boundary not drawn by a Frenchman’s ruler, a single river flows, the Grionde, making possible a meagre settled agriculture. Peanuts constitute the principal export crop: the doughty legumes are shelled by the ton and crushed by village women in immemorial mortars or else by antiquated presses manufactured in Lyons; then the barrelled oil is caravanned by camelback and treacherous truck to Dakar, where it is shipped to Marseilles to become the basis of heavily perfumed and erotically contoured soaps designed not for my naturally fragrant and affectionate countrymen but for the antiseptic lavatories of America — America, that fountainhead of obscenity and glut. Our peanut oil travels westward the same distance as eastward our ancestors plodded, their neck-shackles chafing down to the jugular, in the care of Arab traders, to find from the flesh-markets of Zanzibar eventual lodging in the harems and palace guards of Persia and Chinese Turkestan. Thus Kush spreads its transparent wings across the world. The ocean of desert between the northern border and the Mediterranean littoral once knew a trickling traffic in salt for gold, weight for weight; now this void is disturbed only by Swedish playboys fleeing cold boredom in Volvos that soon forfeit their seven coats of paint to the rasp of sand and the roar of their engines to the omnivorous howl of the harmattan. They are skeletons before their batteries die. Would that Allah had so disposed of all infidel intruders!’

“‘My country of Kush, landlocked between the mongrelized, neo-capitalist puppet states of Zanj and Sahel, is small for Africa, though larger than any two nations of Europe. Its northern half is Saharan; in the south, forming the one boundary not drawn by a Frenchman’s ruler, a single river flows, the Grionde, making possible a meagre settled agriculture. Peanuts constitute the principal export crop: the doughty legumes are shelled by the ton and crushed by village women in immemorial mortars or else by antiquated presses manufactured in Lyons; then the barrelled oil is caravanned by camelback and treacherous truck to Dakar, where it is shipped to Marseilles to become the basis of heavily perfumed and erotically contoured soaps designed not for my naturally fragrant and affectionate countrymen but for the antiseptic lavatories of America — America, that fountainhead of obscenity and glut. Our peanut oil travels westward the same distance as eastward our ancestors plodded, their neck-shackles chafing down to the jugular, in the care of Arab traders, to find from the flesh-markets of Zanzibar eventual lodging in the harems and palace guards of Persia and Chinese Turkestan. Thus Kush spreads its transparent wings across the world. The ocean of desert between the northern border and the Mediterranean littoral once knew a trickling traffic in salt for gold, weight for weight; now this void is disturbed only by Swedish playboys fleeing cold boredom in Volvos that soon forfeit their seven coats of paint to the rasp of sand and the roar of their engines to the omnivorous howl of the harmattan. They are skeletons before their batteries die. Would that Allah had so disposed of all infidel intruders!’

“‘To the south, beyond the Grionde, there is forest, nakedness, animals, fever, chaos. It bears no looking into. Whenever a Kushite ventures into this region, he is stricken with mal à l’estomac.’

“‘Kush is a land of delicate, delectable emptiness, …’

“‘In area Kush measures 126,912,180 hectares. The population density comes to .03 per hectare. In the vast north it is virtually immeasurable. The distant glimpsed figure blends with the land as the blue hawk blends with the sky. There are twenty-two miles of railroad and one hundred seven of paved highway. Our national airline, Air Kush, consists of two Boeing 727′s, stunning as they glitter above the also glittering tin shacks by the airfield. … The natives extract ingenious benefits from the baobab tree, weaving mats from its fibrous heart, ropes from its inner bark, brewing porridge and glue and a diaphoretic for dysentery from the pulp of its fruit, turning the elongated shells into water scoops, sucking the acidic and refreshing seeds, and even boiling the leaves, in desperate times, into a kind of spinach. When are times not desperate? Goats eat the little baobab trees, so there are only old giants. The herds of livestock maintained by the tribes of pastoral nomads have been dreadfully depleted by the drought. The last elephant north of the Grionde gave up its life and its ivory in 1959, with a bellow that still reverberates. “The toubabs took the big ears with them,” is the popular saying. Both Sahel and Zanj possess quantities of bauxite, manganese, and other exploitable minerals, but aside from a streak of sulphur high in the Bulub Mountains the only known mineral deposit in Kush is the laterite that renders great tracts of earth unarable, (I am copying these facts from an old Statesman’s Year-Book, freely, here where I sit in sight of the sea, so some of them may be obsolete.) In the north there were once cities of salt populated by slaves, who bred and worshipped and died amid the incessant cruel glisten; these mining settlements, supervised by the blue-clad Tuareg, are mere memories now.’

“‘But even memory thins in this land, which suggests, on the map, an angular skull whose cranium is the empty desert. Along the lower irregular line of the jaw, carved by the wandering brown river, there was a king, the Lord of Wanjiji, whose physical body was a facet of God so radiant that a curtain of gold flakes protected the eyes of those entertained in audience from his glory; and this king, restored to the throne as a constitutional monarch in the wake of the loi-cadre of 1956 and compelled to abdicate after the revolution of 1968, has been all but forgotten. Conquerors and governments pass before the people as dim rumors, as entertainment in a hospital ward. Truly, mercy is interwoven with misery in the world wherever we glance.’

“‘Among the natural resources of Kush perhaps should be listed our diseases-an ample treasury which includes, besides famine and its edema and kwashiorkor, malaria, typhus, yellow fever, sleeping sickness, leprosy, bilharziasis, onchocerciasis, measles, and yaws. As these are combatted by the genius of science, human life itself becomes a disease of the overworked, eroded earth. The average life expectancy in Kush is thirty-seven years, the per capita gross national product $79, the literacy rate 6%.’

“‘The official currency is the lu. The flag is a plain green field. The form of government is a constitutional monarchy with the constitution suspended and the monarch deposed. An eleven-man Supreme Counseil Revolutionnaire et Militaire pour l’Emergence serves as the executive arm of the government and also functions as its legislature. The pure and final socialism envisioned by Marx, the theocratic populism of Islam’s periodic reform movements: these transcendent models guide the council in all decisions. SCRME’S chairman, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, Minister of National Defense, and President of Kush was (is, the Statesman’s Year-Book has it) Colonel Hakim Felix Ellellou–that is to say, myself.'”

So what does John Updike have in common with Lee Miller, Slim Keith, Amelia Earhart, Buster Keaton, James Baldwin, Greta Garbo, Ian Curtis, Bill Cunningham, Lee Radizwill, Lauren Hutton, Humphrey Bogart, and Tony Leung (In the Mood for Love)?

So what does John Updike have in common with Lee Miller, Slim Keith, Amelia Earhart, Buster Keaton, James Baldwin, Greta Garbo, Ian Curtis, Bill Cunningham, Lee Radizwill, Lauren Hutton, Humphrey Bogart, and Tony Leung (In the Mood for Love)?