First U.K. Edition

The “about” tab says it all: “The concept of Colin’s Review is pretty self-explanatory. My name is Colin, and I review things. So, why should you care? Professional criticism is a dying industry. Ask any journalist or newspaper staff-writer and they’ll unfortunately tell you the same thing. However, there still exists a large contingency of readers who long for the golden era when criticism itself was just as artful as the topics the authors were reviewing. That’s what I strive to provide on this blog.”

So far he’s only reviewed four books (and Updike might be cringing somewhere to discover that Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater merited an A while Rabbit, Run was awarded an A-), but Colin seems insightful, somewhat bold, and quite readable. In his review, after summarizing Updike’s first Rabbit novel in two sentences, Colin writes,

“It makes for a very funny premise, and when told through Updike’s extremely poetic and occasionally profound style, it makes for a very compelling read. After all, the masculine urge for escape is relatable to everyone. Or, rather, Updike’s such a talented writer that Rabbit’s masculine impulses are easy to empathize with. The further he self-destructs, the more human he becomes.

“Then again, Rabbit isn’t exactly the most likable protagonist . . . . Watching him constantly take advantage of those around him would be quite exhausting if it wasn’t for Updike’s wit and clarity. Not to mention the book’s present tense P.O.V., which keeps Rabbit’s cycle of assholery refreshing despite its repetition—an uncomfortable and entertaining read.

“Back in 1960, Rabbit, Run provided a fresh perspective: a window into the soul of American men disillusioned with the middle-class WASP lifestyle, searching for spirituality but lacking religion, obsessed with sex yet scared of commitment, desperate for meaning in a seemingly meaningless world. Admirable cowards, self-righteous fools.”

Colin notes that Updike had such an “immense” influence that “thousands of similar characters” have “taken up Rabbit’s running-away-from-family mantle. From American Pastoral to Cosmopolis to Five Easy Pieces, there’s no shortage of problematic white male protagonists. Then again, I can’t blame Updike for a half-century of imitators.”

The brisk review is made even brisker with sections on “Further Reading,” “Stray Observations (including Spoilers),” and “Quotes from Rabbit, Run.”

Read the full review

In an opinion piece for The Times (UK), Benjamin Markovits writes that he doesn’t remember reading John Updike’s Rabbit, Run when it first came out in 1960, partly because he was “suspicious” of the book’s popularity and was hesitant about such things as the “breathless present tense” of the narrative or the opening scene that has Rabbit knocking down a jump shot without even taking off his double-breasted jacket. “But then, just recently, I reread it and was stunned again by how good it is. The basic story hasn’t grown old either.”

In an opinion piece for The Times (UK), Benjamin Markovits writes that he doesn’t remember reading John Updike’s Rabbit, Run when it first came out in 1960, partly because he was “suspicious” of the book’s popularity and was hesitant about such things as the “breathless present tense” of the narrative or the opening scene that has Rabbit knocking down a jump shot without even taking off his double-breasted jacket. “But then, just recently, I reread it and was stunned again by how good it is. The basic story hasn’t grown old either.”

The Philip Roth and John Updike societies announced that registration is now open to participate in a joint conference to be held in New York City, Oct. 19-22, 2025.

The Philip Roth and John Updike societies announced that registration is now open to participate in a joint conference to be held in New York City, Oct. 19-22, 2025.

Today’s Washington Post featured a Q&A, “Post critic Michael Dirda turns a page: Dirda discusses the life of a critic, and his decision for a change of pace after 30 years of weekly columns,” in which John Updike merited a brief mention.

Today’s Washington Post featured a Q&A, “Post critic Michael Dirda turns a page: Dirda discusses the life of a critic, and his decision for a change of pace after 30 years of weekly columns,” in which John Updike merited a brief mention.

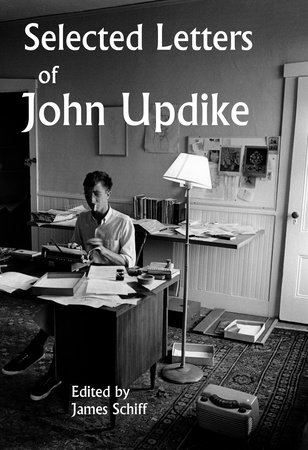

Knopf, now a division of Penguin-Random House, just released cover art for Selected Letters of John Updike, edited by Updike scholar and John Updike Society vice-president James Schiff. The hefty hardcover (900 pages) is roughly 6×9″ and slated for October 21, 2025 release. A book release event and signing will be scheduled as part of the joint Roth-Updike societies’ conference in New York City, Oct. 19-22. Those who plan on attending should count on getting a copy in NYC.

Knopf, now a division of Penguin-Random House, just released cover art for Selected Letters of John Updike, edited by Updike scholar and John Updike Society vice-president James Schiff. The hefty hardcover (900 pages) is roughly 6×9″ and slated for October 21, 2025 release. A book release event and signing will be scheduled as part of the joint Roth-Updike societies’ conference in New York City, Oct. 19-22. Those who plan on attending should count on getting a copy in NYC. Of Updike’s novel she writes, “Mining, as did [Dorothy] Dunnett, some of Shakespeare’s own sources, Updike relied partly on Saxo Grammaticus’ twelth-century saga of Amlothi for details about the characters on which his Danish king and queen are based.

Of Updike’s novel she writes, “Mining, as did [Dorothy] Dunnett, some of Shakespeare’s own sources, Updike relied partly on Saxo Grammaticus’ twelth-century saga of Amlothi for details about the characters on which his Danish king and queen are based. Sixties’ icon Marianne Faithfull, a singer-songwriter who was considered a major figure in the so-called “British Invasion” of U.K. music to hit the U.S. during the turbulent decade,

Sixties’ icon Marianne Faithfull, a singer-songwriter who was considered a major figure in the so-called “British Invasion” of U.K. music to hit the U.S. during the turbulent decade,