Distinguished poet, writer, translator, and Shakespearian scholar Alexander Shurbanov, who translated John Updike’s novel Gertrude and Claudius into Bulgarian, will be featured as a keynote speaker at the Fifth Biennial John Updike Society Conference in Serbia. The conference, 1-4 June 2018, will be sponsored and hosted by the Faculty of Philology at the University of Belgrade.

Distinguished poet, writer, translator, and Shakespearian scholar Alexander Shurbanov, who translated John Updike’s novel Gertrude and Claudius into Bulgarian, will be featured as a keynote speaker at the Fifth Biennial John Updike Society Conference in Serbia. The conference, 1-4 June 2018, will be sponsored and hosted by the Faculty of Philology at the University of Belgrade.

Not only did Shurbanov, now Professor Emeritus at the University of Sofia in Bulgaria, correspond with Updike while translating Gertrude and Claudius, but he was also a longtime friend of Blaga Dimitrova, the prototype of Vera Glavanakova from Updike’s O. Henry Award-winning story “The Bulgarian Poetess.”

Shurbanov, who has also taught at the University of London, UCLA, and SUNY-Albany, has translated 14 texts ranging from Chaucer, Shakespeare, and the Magna Carta to Tales by Beatrix Potter and poetry by Milton, Coleridge, Dylan Thomas, Ted Hughes, and Rabindranath Tagore. As a poet and essayist he is also the author of 18 collections, including three bilingual Bulgarian-English titles: Frost-Flowers (Princeton, 2001), Beware: Cats (Sofia, 2001), and most recently Foresun: Selected Poems in Bulgarian and English (Sofia, 2016).

From 1972-2009, Shurbanov taught at the University of Sofia, where he received The Honorary Medal of Sofia University in 2001. He is also the recipient of numerous other awards, including The Danov National Award for Overall Contribution to Culture (2007), The Geo Miley National Literary Award (2015), and The Portal Kultura Special Prize for Notable Achievements in Poetry and Translation (2016).

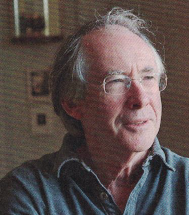

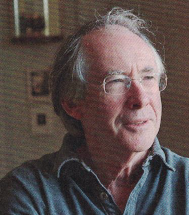

Along with celebrated writer Ian McEwan, who was announced earlier as a keynote speaker, the addition of Professor Shurbanov gives the conference two top-flight presenters that should appeal to both society members and devotees of literature. Like Updike, whom he knew, McEwan worked in multiple genres, the author of 14 novels, three short story collections, two plays, two children’s books, five screenplays—even a libretto. Among his numerous awards are the Booker Prize for his eighth novel, Amsterdam (1998); the Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in Society (2011); and the 50th Anniversary Gold Medal from the University of Sussex. Long an advocate for Updike’s legacy and an admitted beneficiary of Updike’s influence, McEwan is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, the Royal Society of Arts, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His most recent novel is Nutshell (2016)—which retells the story of Shakespeare’s Hamlet from the point of view of an unborn child.

Along with celebrated writer Ian McEwan, who was announced earlier as a keynote speaker, the addition of Professor Shurbanov gives the conference two top-flight presenters that should appeal to both society members and devotees of literature. Like Updike, whom he knew, McEwan worked in multiple genres, the author of 14 novels, three short story collections, two plays, two children’s books, five screenplays—even a libretto. Among his numerous awards are the Booker Prize for his eighth novel, Amsterdam (1998); the Jerusalem Prize for the Freedom of the Individual in Society (2011); and the 50th Anniversary Gold Medal from the University of Sussex. Long an advocate for Updike’s legacy and an admitted beneficiary of Updike’s influence, McEwan is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, the Royal Society of Arts, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His most recent novel is Nutshell (2016)—which retells the story of Shakespeare’s Hamlet from the point of view of an unborn child.

Though membership in the society is required to attend the conference, The John Updike Society is an inclusive organization whose members are teachers, professors, writers, theologians, independent scholars, Updike family and friends, collectors, and the kind of just-plain-readers that Updike always appreciated. The society previously held conferences in Columbia, S.C., Boston, and Reading, Pa. (twice). This will be the first time members will meet outside the U.S.

Call for papers

Redux. From the Latin, meaning, “to lead back.” And an article on “The Top 10 Words That Died and Were Reborn,” written by John Rentoul and published in The Independent, credits John Updike for the revival:

Redux. From the Latin, meaning, “to lead back.” And an article on “The Top 10 Words That Died and Were Reborn,” written by John Rentoul and published in The Independent, credits John Updike for the revival: