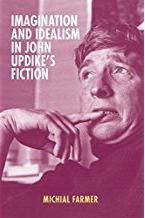

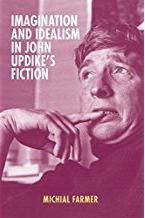

We’re just learning about it now, but the podcast series Christian Humanist Profiles interviewed Michael Farmer last year about his book, Imagination and Idealism in John Updike’s Fiction. Nathan P. Gilmour asked the questions for the podcast “Christian Humanist Profiles 115,” which he introduced by talking about the philosophy of religion:

We’re just learning about it now, but the podcast series Christian Humanist Profiles interviewed Michael Farmer last year about his book, Imagination and Idealism in John Updike’s Fiction. Nathan P. Gilmour asked the questions for the podcast “Christian Humanist Profiles 115,” which he introduced by talking about the philosophy of religion:

“Immanuel Kant famously distinguished between things, existing as they are, impervious to our mental probings, and objects, those pieces of our world that only come to us as organized and mediated by senses and understanding and concepts. Later on, philosophers who would come to be called existentialists–whether they liked it or not–came to regard the imagination, our mental power of organizing and even shaping our world, as one of the core realities of human existence. Michial Farmer, in his recent book Imagination and Idealism in John Updike’s Fiction, follows the course of imagination as a weapon, an escape, and sometimes even as a mode of redemption in John Updike’s novels and stories and poems, and today he’s joining us on Christian Humanist Profiles not as interviewer but as author” (In “Christian Humanist Profiles 195: The Watchmen” Farmer interviewed Gilmour and David Grubbs about Alan Jacobs’ essay by that title).

Echoing Updike himself, Farmer says that “the work of art is an act of seeing” that “creates a new world.” He says that Updike’s writing depicts a world where “humanity wrestles with the material world and ritual longings.”

Farmer describes the “mechanized universe” as both attractive and repelling. “Updike is fascinated by science, and he’s terrified by it,” Farmer says. “He sees a universe that is meaningless, but he can’t accept that, and something deep within him revolts against it.”

Farmer suggests that Updike’s philosophy aligns, to some degree, with atheist existentialism. “Updike conceives of faith as an act of the imagination where you’re imprinting meaning on an apparently meaningless universe,” Farmer says. “Whatever meaning you’re going to find in the universe, you’re going to put into the universe.”

Farmer suggests that Updike’s philosophy aligns, to some degree, with atheist existentialism. “Updike conceives of faith as an act of the imagination where you’re imprinting meaning on an apparently meaningless universe,” Farmer says. “Whatever meaning you’re going to find in the universe, you’re going to put into the universe.”

The theory of “parents forming a mythology for their children” also comes up. Farmer wonders whether Updike’s mother served as a “mythological figure” in both life and fiction as she “dominated his early life and central trauma of his childhood.”

Farmer emphasizes the dependence of the mind in forming the fundamental meaning for life. He concludes, “the only solution to the loss of faith in the modern world is to increase the imagination.”

Listen to the podcast here.

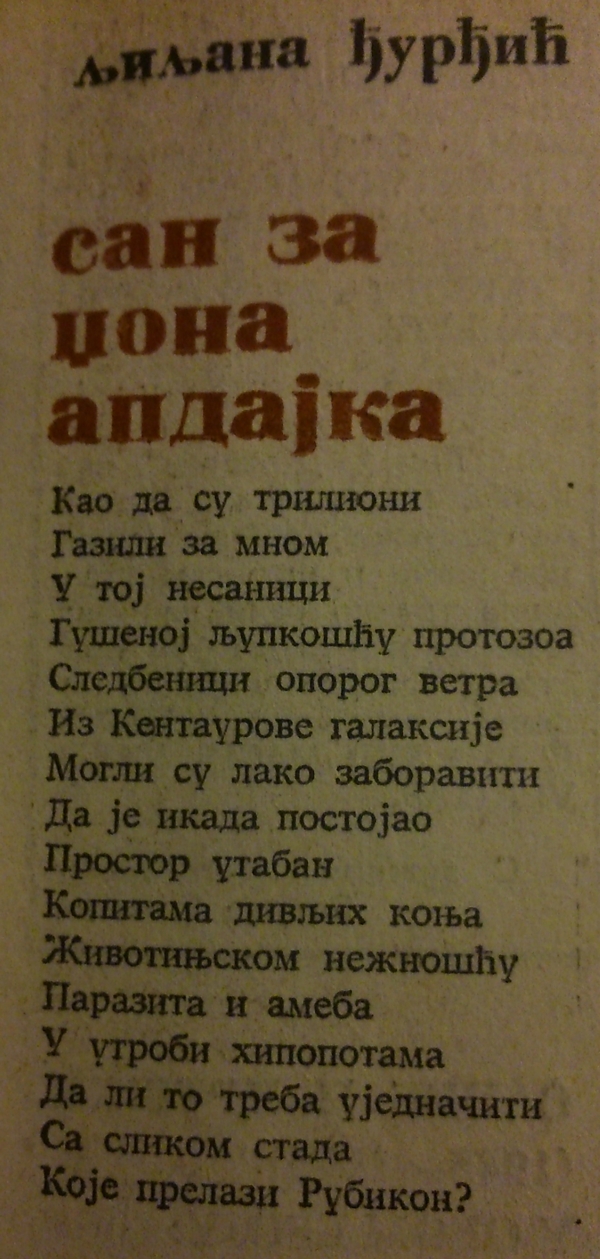

Professor Biljana Dojčinović from the Faculty of Philology, University of Belgrade, has edited and published the Book of Abstracts for The Fifth Biennial John Updike Society Conference, which will be hosted by the Faculty of Philology 1-5 June 2018.

Professor Biljana Dojčinović from the Faculty of Philology, University of Belgrade, has edited and published the Book of Abstracts for The Fifth Biennial John Updike Society Conference, which will be hosted by the Faculty of Philology 1-5 June 2018.