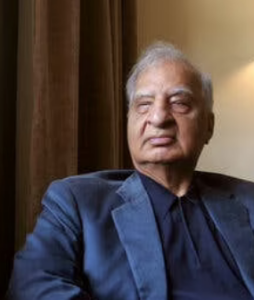

We are saddened to report that Harlan L. Boyer, who graduated from Shillington High School in 1950 and was a classmate of John Updike’s, died on Monday, March 1, 2021. He was 88. Boyer, whose father was Updike’s art teacher at Shillington High School, was the only male childhood friend invited to play inside the Updike house at 117 Philadelphia Ave. Boyer said that he and young Updike mostly played in the dining room just off the side porch, and that a favorite pastime was setting up dominoes on the sideboard and then knocking them down. When told about a handful of marbles that were found under a loose floorboard in the Black Room adjacent to Updike’s boyhood bedroom, Boyer said that they never really played much marbles. Rather, they would shoot them with their slingshots. Updike, he guessed, probably shot at something from his bedroom window, then panicked and hid the marbles.

We are saddened to report that Harlan L. Boyer, who graduated from Shillington High School in 1950 and was a classmate of John Updike’s, died on Monday, March 1, 2021. He was 88. Boyer, whose father was Updike’s art teacher at Shillington High School, was the only male childhood friend invited to play inside the Updike house at 117 Philadelphia Ave. Boyer said that he and young Updike mostly played in the dining room just off the side porch, and that a favorite pastime was setting up dominoes on the sideboard and then knocking them down. When told about a handful of marbles that were found under a loose floorboard in the Black Room adjacent to Updike’s boyhood bedroom, Boyer said that they never really played much marbles. Rather, they would shoot them with their slingshots. Updike, he guessed, probably shot at something from his bedroom window, then panicked and hid the marbles.

Boyer had a wealth of stories to share, and members of The John Updike Society will fondly recall his participation on the classmates panel at the society’s first conference in Reading, Pa. In the years that followed he was generous with his time, always willing to answer scholars’ questions about his relationship with “Uppy,” as he called the author back when they were children.

According to the Reading Eagle obituary, Boyer served as a U.S. Navy pilot during the Korean Conflict and later earned a Master’s in Guidance and Counseling, serving 12 years in the Governor Mifflin School District and 23 years at Schuylkill Valley School District before retiring in 1992. A 32 Degree Mason, Boyer had a passion for airplanes and in his later years enjoyed tending to his two acres of property. The society offers our sympathies to his wife Beverly, son Kirk, and daughter Kirstin. We will miss him too.

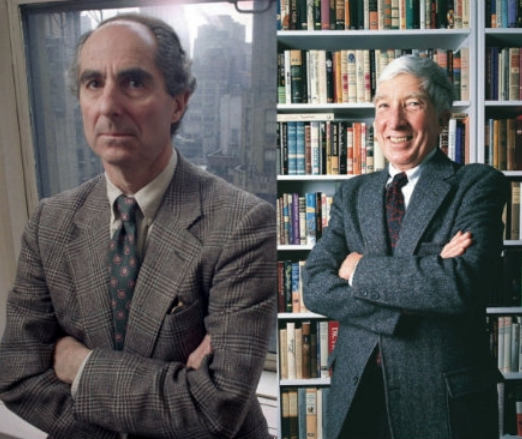

Class of 1950 panel from the 2010 conference (l to r): Moderator Jack De Bellis, Joan Youngerman, Jackie Hirneisen Kendall, Harlan Boyer, Jimmie Trexler

Class of 1950 panel from the 2010 conference (l to r): Moderator Jack De Bellis, Joan Youngerman, Jackie Hirneisen Kendall, Harlan Boyer, Jimmie Trexler

In a Q&A with The Nerd Daily, Jennifer Dupee, author of the debut novel The Little French Bridal Shop, was asked, “Was there a moment in your writing career where you thought, ‘Okay, now I am officially a REAL writer?’ Can you tell us about that time in your life?”

In a Q&A with The Nerd Daily, Jennifer Dupee, author of the debut novel The Little French Bridal Shop, was asked, “Was there a moment in your writing career where you thought, ‘Okay, now I am officially a REAL writer?’ Can you tell us about that time in your life?”