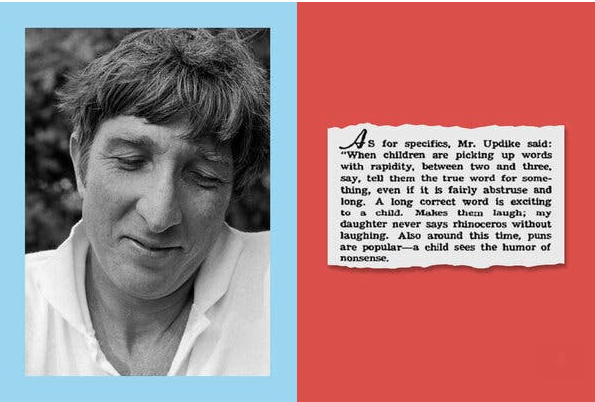

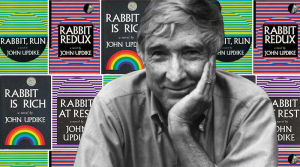

In a piece that appeared in yesterday’s Sunday Times [London], Claire Lowdon asked the question, “Should we stop reading the work of Saul Bellow, John Updike and Philip Roth?”

Then she provided an answer: “Let’s judge the great male literary figures on merit, not by their sexual deeds.” But she did not come to that decision without a struggle.

“Never do I feel more trapped inside my gender than when I’m thinking about Philip Roth, John Updike and Saul Bellow. But not for the reasons you might think,” Lowdon wrote.

“These novelists dominated the American literary scene for 50 years. Boldly, shamelessly, their work mined their lives and those of the people they knew. Over the past decade important biographies of all three have appeared, flooding those lives with the cold, hard light of non-fiction. The promiscuity and the adultery we already knew about. But the scale of it! Sometimes Bellow had four women on the go at once. Or how about Updike, who pleasured his mistress through her ski trousers in the back seat of the car his unwitting wife was driving? And Roth, whose later work seems so noble, so serious—why there he is, caught red-handed in Blake Bailey’s new biography, using prostitutes and sleeping with his students!”

“These novelists dominated the American literary scene for 50 years. Boldly, shamelessly, their work mined their lives and those of the people they knew. Over the past decade important biographies of all three have appeared, flooding those lives with the cold, hard light of non-fiction. The promiscuity and the adultery we already knew about. But the scale of it! Sometimes Bellow had four women on the go at once. Or how about Updike, who pleasured his mistress through her ski trousers in the back seat of the car his unwitting wife was driving? And Roth, whose later work seems so noble, so serious—why there he is, caught red-handed in Blake Bailey’s new biography, using prostitutes and sleeping with his students!”

Lowdon wrote that ironically “we perform a piece of sexist reduction when all we care about is what Roth [and Updike and the others] did in bed. And although, increasingly, it’s considered reactionary to say, ‘Hold on, things were a bit different back then,’ it’s true: they were. The way we think about sex and power has shifted radically in the past half-century.”

She continued, “Roth, Updike and Bellow are our fathers in the sense that we have inherited the world in which they lived and wrote. Perhaps we simply can’t bear to discover that these once-revered figures are less than perfect. An uncomfortable truth: a man who is capable of great insights into the human condition can desire in his dotage to f*** a much younger woman. Are we afraid of what these men have to tell us about sex—that it is full of inconvenient, transgressive, inappropriate feelings?”

Lowdon concluded, “The world is messy, full of unwanted erections and coercion and pornography. Good novelists try to capture that mess on paper. Which is in itself a moral act—to look clearly and unflinchingly at what is.”

Read the full essay.