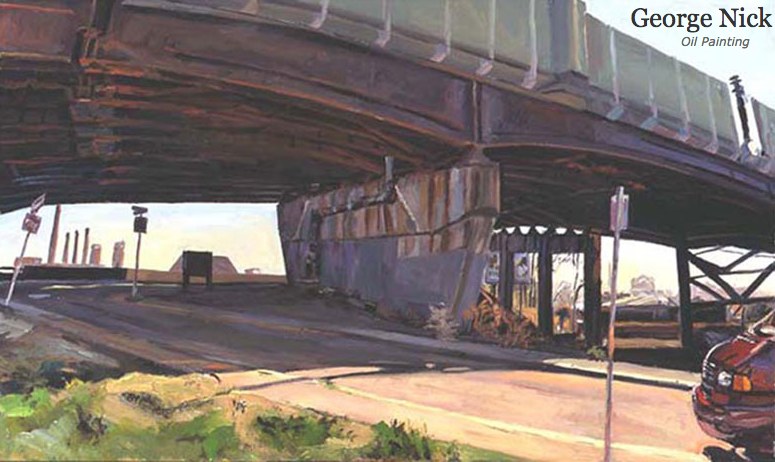

The John Updike Society is now accepting proposals for papers to be presented at the Sixth Biennial John Updike Society Conference at Alvernia University, Reading, Pennsylvania, in fall 2020. The conference will coincide with the October 3 grand opening and October 3 dedication of the newly restored John Updike Childhood Home in Shillington, Pennsylvania, which the Society purchased in 2012 and has turned into a museum. Attendees will also be able to register for group side trips to Updike sites in Berks County and/or a day trip to Philadelphia.

We welcome one-page proposals for 15-20 minute papers on all aspects of Updike’s life and work, but especially seek proposals on:

—Works dealing with Updike’s childhood as described in his fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, including Midpoint, Pigeon Feathers, Self-Consciousness, The Centaur, and Olinger Stories.

—Updike works celebrating a milestone anniversary in 2020: Rabbit, Run (60th), Bech: A Book (50th), Rabbit at Rest (30th), and Gertrude and Claudius (20th).

—Toward the End of Time, since 2020 is the year in which the novel is set.

We will also entertain proposals for panel discussions focused on individual works, groups of works, or themes in Updike’s fiction, poetry, and nonfiction. Scholars who have recently published a book or are in the process of writing a book on Updike are encouraged to submit proposals for panel discussions.

Send proposal and a brief one- or two-paragraph bio to: Program director Larry Mazzeno: larry.mazzeno@alvernia.edu.

Successful proposals will be acknowledged within two weeks of receipt. To present a paper or moderate a panel at the conference, participants must be members of The John Updike Society and register for the conference. For membership information, see the Society’s website at https://blogs.iwu.edu/johnupdikesociety/join. Those who have papers accepted can join when they register for the conference. Registration information and further conference information will be forthcoming.

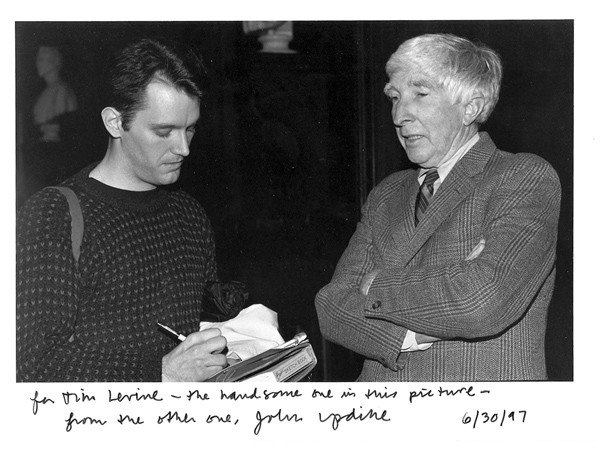

The very first John Updike Society conference was hosted by Alvernia University in 2010 (Ann Beattie, Lincoln Perry keynotes), with the second conference held at Suffolk University in Boston (Joyce Carol Oates, keynote), the third at Alvernia again (Adam Begley, Chip Kidd keynotes), the fourth at the University of South Carolina (Garrison Keillor keynote), and the fifth at the University of Belgrade in Serbia (Ian McEwan keynote). All are welcome to attend, whether presenting papers or not, as the John Updike Society is a gregarious blend of scholars, teachers, aficionados, Updike family and friends, and the kind of “just plain readers” that Updike so appreciated.

A subscription is required, but if you’re high on golf and John Updike, as Matt Chominski is, you can plunk down the cash and read Chominski’s personal essay “Peculiar Bliss: Navigating family, marriage and golf with John Updike” that appears in the print-only Golfer’s Journal No. 9. Also in the issue is “The Bard’s Butter Cut: A Meeting and a match with Billy Collins, America’s rock-star poet.”

A subscription is required, but if you’re high on golf and John Updike, as Matt Chominski is, you can plunk down the cash and read Chominski’s personal essay “Peculiar Bliss: Navigating family, marriage and golf with John Updike” that appears in the print-only Golfer’s Journal No. 9. Also in the issue is “The Bard’s Butter Cut: A Meeting and a match with Billy Collins, America’s rock-star poet.”