When you’ve been a book critic as long as Craig Brown has, you deserve one of the longest headlines in recent memory: “Why, after 23 years and 1.5 million words as Mail on Sunday’s book critic, I think Jade Goody is up there with Dickens’: After writing the equivalent of War and Peace (twice), CRAIG BROWN hangs up his pen – and remembers 20 titles he most enjoyed reading.”

Click on the link above to read his farewell remarks.

As for the “20 Most Memorable Books I’ve Reviewed,” here they are:

Waterlog—Roger Deakin

The Suspicions of Mr Whicher—Kate Summerscale

Birds and People—Mark Cocker

Once Upon a Secret—Mimi Alford

Madeleine—Kate McCann

A Very English Scandal—John Preston

This Boy: A Memoir of a Childhood—Alan Johnson

The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power—Robert A. Caro

Out of Sheer Rage—Geoff Dyer

Untold Stories—Alan Bennett

Simon Gray’s Diaries—Simon Gray

Terms and Conditions: Life in Girls’ Boarding Schools, 1939-1979—Ysenda Maxtone Graham

Tamara Drewe—Posy Simmonds

The Man Who Went into the West—Byron Rogers

The Examined Life—Stephen Grosz

The Year of Magical Thinking—Joan Didion

The New Biographical Dictionary of Film—David Thomson

Anne Tyler’s Novels—yes, any of them

Tales of a New Jerusalem—David Kynaston

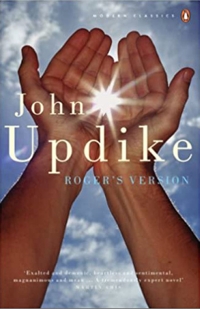

Endpoint and Other Poems—John Updike

“Updike died in 2009, having written more than 50 books, all of them, as Tobias Wolff once observed, ‘suffused with the pleasure of simply being alive’. Ths posthumously published book of poems, written when the end was in sight, is full of wonder and delight.”