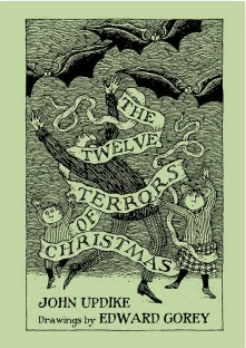

Shepherd, a blog for book lovers, recently posted an article by Jóhannes úr Kötlum on “10 books like Christmas is Coming” that starts with Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, but instantly moves on to other ghost stories or creepy tales, like The Krampus and the Old, Dark Christmas by Al Ridenour, The Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Walter Scott, and Updike’s The Twelve Terrors of Christmas, illustrated by Edward Gorey.

“No list of the delightfully dark would be complete without an appearance by the preeminent gothic illustrator, Edward Gorey. Gorey’s wry, one-of-a-kind style brings to life (and death) John Updike’s dark deconstruction of 12 Christmas traditions. Though it’s now out of print, this title is a must-have for any Edward Gorey enthusiast, and for any fan of the unlimited imaginative potential when artists look beyond the lights of the holiday season to focus on the shadows instead,” Kötlum writes.

Rounding out the list are The Elves And The Shoemaker by the Brothers Grimm and Jim LaMarche, Collected Ghost Stories by M.R. James, A Yuletide Kiss by Glynnis Campbell, The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus by L. Frank Baum, Six Geese a Laying by Emily E.K. Murdoch, and a holiday book not yet ready to give up the ghost: Dark Halloween by Eleanor Merry, Cassandra Angler, and Brian Scutt.