This sounds like a fun course: Witchcraft in Literature 101. You can take it, too, online, and for free from Arcadia, thanks to researcher-author Anna Artyushenko.

“Witchcraft takes on many forms and perspectives in various works of literature, Artyushenko wrote. “It finds its origins in folklore and myths, it carries the traits of gothic and horror, but it is also used in satire and comedy, and undoubtedly plays a major role in fantasy.”

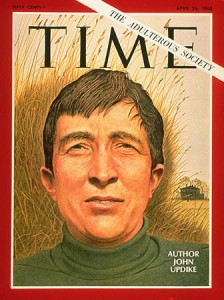

Updike’s 1984 novel is the subject of the third post, “Social Commentary in The Witches of Eastwick“:

“All three witches possess some powers at the outset of the novel, but their abilities develop and turn darker with the arrival of Darryl Van Horne. It is never stated directly in the novel that the stranger who has arrived in Eastwick is the Devil. However, his nature is obvious, according to many remarks in the novel. Updike purposefully plays around the “stranger danger” trope, inviting the Devil to the small conservative town of New England. He ridicules the reception of the occult in the traditional Puritan society, though “God’s absence, presumably, opens the way for evil” in the novel (Verduin, 1985, p. 306). Van Horne is purposefully drawn to the witches and corrupts their powers. The women cannot escape the stereotypical pattern, as “in order to satisfy their extraordinary sexual appetite, the witches turn to a devil figure, Darryl Van Horne” (Loudermilk, 2013, p. 101).”

“Updike makes a reference to the Wiccan perception of magic, connecting it with nature, though his vision of witchcraft is “closely tied to both, carnality and mortality” (Antwood, 1984, para. 10). Updike sees nature not from a spiritual or ecological, but from a rational perspective: incapable of empathy towards humankind, and as inseparable from death and decay as it is from life and growth. In the novel Alexandra thinks that one of the major nature’s rules is “that there must always be a sacrifice” (Updike, 1996, p. 18). Jenny becomes this victim, sacrificed to the Devil. Updike makes a point that the male’s power is still greater, as later on the witches learn that they did not cast the curse out of their own free will and were controlled by Van Horne. The Devil in the novel acts as a trickster who manipulates the witches while they abandon their family duties in order to follow the path of the occult and magic, which leaves them with nothing but regret in the end.”

Read the entire article.