The Atlantic‘s Robinson Meyer contributed a piece on “How to Write a History of Writing Software,” subtitled “Isaac Asimov, John Updike, and John Hersey changed their writing habits to adapt to word processors, according to the first literary historian of the technology.” Meyer interviewed University of Maryland English professor Matthew Kirschenbaum, who has just published the first book-length history of word processing, Track Changes.

“It is more than a history of high art. Kirschenbaum follows how writers of popular and genre fiction adopted the technology long before vaunted novelists did. He determines how their writing habits and financial powers changed once they moved from typewriter to computing. And he details the unsettled ways that the computer first entered the home. (When he first bought a computer, for example, the science-fiction legend Isaac Asimov wasn’t sure whether it should go in the living room or the study.)

“His new history joins a much larger body of scholarship about other modern writing technologies—specifically, typewriters. For instance, scholars confidently believe that the first book ever written with a typewriter was Life on the Mississippi, by Mark Twain. They have conducted typographical forensics to identify precisely how T.S. Elioit’s The Wasteland was composed—which typewriters were used, and when. And they have collected certain important machines for their archives.”

“His new history joins a much larger body of scholarship about other modern writing technologies—specifically, typewriters. For instance, scholars confidently believe that the first book ever written with a typewriter was Life on the Mississippi, by Mark Twain. They have conducted typographical forensics to identify precisely how T.S. Elioit’s The Wasteland was composed—which typewriters were used, and when. And they have collected certain important machines for their archives.”

Kirschenbaum says that while he can’t say for certain which writer was first to compose using a word processor or computer, notable candidates are science-fiction author Jerry Pournelle and author John Hersey, who edited Hiroshima on a keyboard and used to computer to generate camera-ready copy.

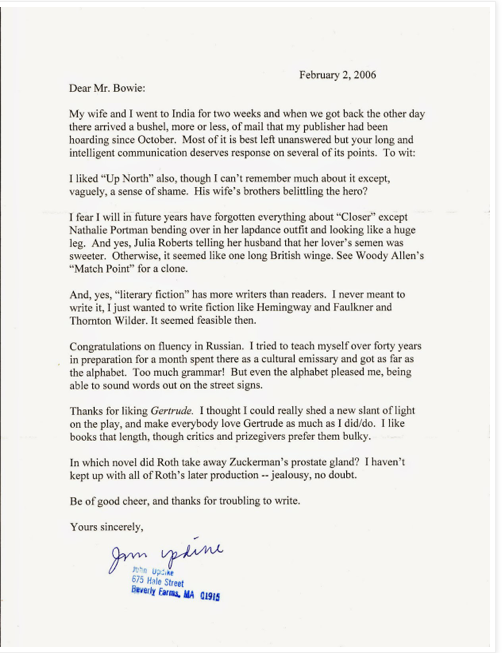

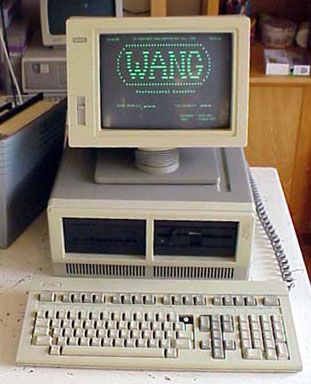

“Another interesting story that’s in the book is about John Updike, who gets a Wang word processor at about the time Stephen King does, in the early 1980s. I was able to inspect the last typewriter ribbon that he used in the last typewriter he owned. A collector who had the original typewriter was kind enough to lend it to me. And you can read the text back off that typewriter ribbon—and you can’t make this stuff up, this is why it’s so wonderful to be able to write history—the last thing that Updike writes with the typewriter is a note to his secretary telling her that he won’t need her typing services because he now has a word processor.”

Pictured: Stock photo of typical Wang word processor from the 1980s.