For his August 16, 2022 post at Ink Spill: New Yorker Cartoonists News, History, and Events, New Yorker cartoonist Michael Maslin began,

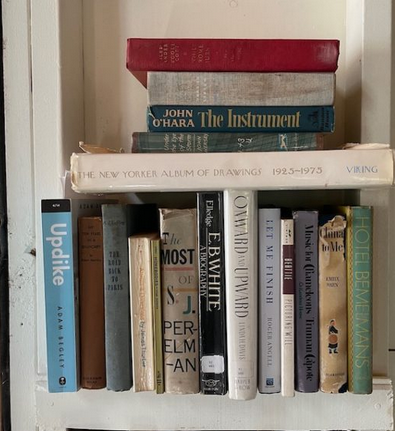

“For the past twenty-seven summers, my wife, Liza Donnelly, and I have gone to the same Downeast home, and over those years, have built a small library of books, some New Yorker-centric (but many having nothing to do with the magazine).” Depicted in the photo are “most of the books either brought here or bought here at library book sales.”

“Occasionally,” Maslin confessed, “I take a book back to New York,” depriving their growing summer library of the volume—such as James Thurber’s The Seal in the Bedroom, which flippered back with them last year at summer’s end.

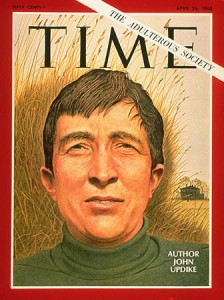

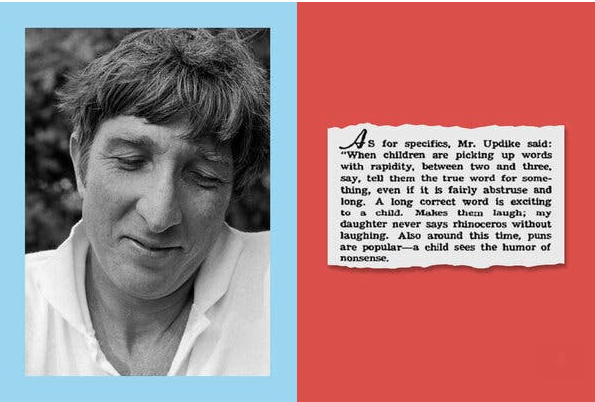

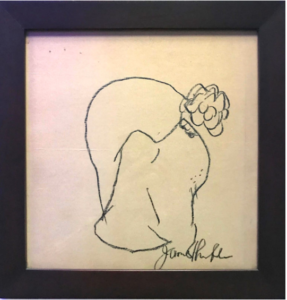

“The titles by Liebling, Benchley, Capote, Beattie are like good friends,” Maslin wrote. “I enjoy seeing them, being around them. Adam Begley’s Updike biography came up with us this year. I’m on my third read through, visiting parts I just had to experience again (last night I re-read the part about Updike driving into Manhattan to meet William Shawn for the very first time, but having to delay the meeting by a day because he (Updike) got lost somewhere in the vicinity of the Pulaski Skyway in New Jersey). Someone should do a collection of pieces about Updike driving. About a decade ago, at a library sale up near the Canadian border, I found a first edition of Updike’s Rabbit, Run (still dust-jacketed) for about 75 cents. That too went back to New York to sit on the Updike shelf.”

Read the entire post