That morsel would be a tiny bit of oatmeal cookie, as it turns out.

The Sept. 10, 2024 entry on the Best American Poetry blog by Nin Andrews features “Advice to Young Poets and a Poem by Kelli Russell Agodon” . . . but also a brief note on writers’ habits that includes Updike:

“Like Timothy Touchett, I enjoy studying other writers’ habits. I want to know what kinds of sorcery they employ. As a result, I can tell you that John Updike ate so much when he wrote, he didn’t like to go out to lunch and worried about his figure. He was partial to oatmeal cookies. Joan Didion edited at the end of the day with a drink in hand (Liquor, of  course, played an important role for a lot writers—no need to list them all here.) John Ashbery enjoyed a nice cup of tea and classical music when he wrote, which was usually in the late afternoon. Charles Simic enjoyed writing when his wife was cooking. Eudora Welty could write anywhere—even in the car— and at any time, except at night when she was socializing. Flannery O’Connor could only write two hours a day and her drink was Coca Cola mixed with coffee. Simone de Beauvoir wrote from 10AM-1PM and from 5-9PM. Louise Glück found writing on a schedule “an annihilating experience.” A. R. Ammons wrote only when inspiration hit—he compared trying to write to trying to force yourself to go the bathroom when you have no urge. Anne Sexton took up writing after therapy sessions. Jack Kerouac had various rituals at different times—one was writing by candlelight, and another was doing “touch downs” which involved standing on his head and touching his toes to the ground. Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf wrote standing up. Wallace Stevens composed poems while walking to work. Gabriel García Márquez listened to the news before writing. Amy Gerstler sometimes listens to recordings of rain while writing. I tried that once, and the rain put me into a deep and dreamless sleep.”

course, played an important role for a lot writers—no need to list them all here.) John Ashbery enjoyed a nice cup of tea and classical music when he wrote, which was usually in the late afternoon. Charles Simic enjoyed writing when his wife was cooking. Eudora Welty could write anywhere—even in the car— and at any time, except at night when she was socializing. Flannery O’Connor could only write two hours a day and her drink was Coca Cola mixed with coffee. Simone de Beauvoir wrote from 10AM-1PM and from 5-9PM. Louise Glück found writing on a schedule “an annihilating experience.” A. R. Ammons wrote only when inspiration hit—he compared trying to write to trying to force yourself to go the bathroom when you have no urge. Anne Sexton took up writing after therapy sessions. Jack Kerouac had various rituals at different times—one was writing by candlelight, and another was doing “touch downs” which involved standing on his head and touching his toes to the ground. Ernest Hemingway and Virginia Woolf wrote standing up. Wallace Stevens composed poems while walking to work. Gabriel García Márquez listened to the news before writing. Amy Gerstler sometimes listens to recordings of rain while writing. I tried that once, and the rain put me into a deep and dreamless sleep.”

This National Windows Day (that’s a thing?), renowned photographer Jill Krementz shared some of the photos she took of

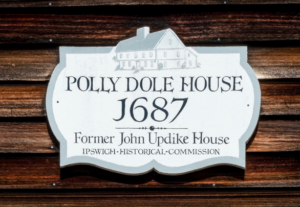

This National Windows Day (that’s a thing?), renowned photographer Jill Krementz shared some of the photos she took of  On May 3, 2024, the “Novelist Spotlight: Interviews and insights with published fiction writers” blog looked in the rear-view mirror to discuss a writer who, according to host and novelist Mike Consol, wrote more beautifully in English than anyone else.

On May 3, 2024, the “Novelist Spotlight: Interviews and insights with published fiction writers” blog looked in the rear-view mirror to discuss a writer who, according to host and novelist Mike Consol, wrote more beautifully in English than anyone else.