Writer John Updike was such a commentator on American society that he’s often cited comparatively or as a cultural touchstone–especially at The New Yorker, where he was the Talk of the Town writer for many years and a frequent contributor of poetry, fiction, essays, and reviews thereafter. The most recent comparison comes from Nikil Saval, who, in his essay on “The Impeccably Understated Modernism of I.M. Pei,” writes,

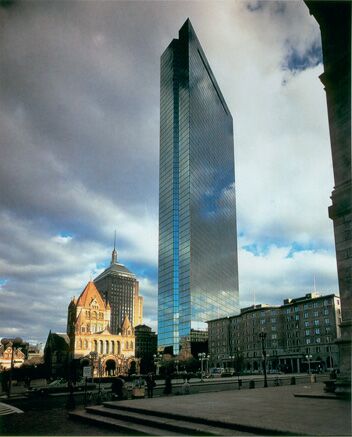

“In John Updike’s story ‘Gesturing,’ first published in 1980, the newly separated Richard Maple finds himself in a Boston apartment with a view of a startling new skyscraper. ‘The skyscraper, for years suspended in a famous state of incompletion, was a beautiful disaster,’ Updike writes, ‘famous because it was a disaster (glass kept falling from it) and disastrous because it was beautiful.’ The architect had imagined that a sheer glass skin would ‘reflect the sky and the old low brick skyline of Boston’ and would ‘melt into the sky.’ ‘Instead,’ Updike continues, ‘the windows of mirroring glass kept falling to the street and were replaced by ugly opacities of black plywood.’ Still, enough of the reflective surface remains ‘to give an impression, through the wavery old window of this sudden apartment, of huge blueness, a vertical cousin to the horizontal huge blueness of the sea that Richard awoke to each morning, in the now bone-deep morning chill of his unheated shack.’ Not too surprisingly, the distressed tower becomes an oblique symbol for the state of Richard’s life, soul, and dissolved marriage, slicing in and out of the story, much as its counterpart slices in and out of the Boston skyline.

“The skyscraper in ‘Gesturing’ is unmistakably the John Hancock Tower (officially renamed 200 Clarendon in 2015), designed by I.M. Pei and finished in 1976,” writes Saval, adding that despite structural problems the building “remains the single most beautiful object in one of the world’s most tedious, stuffy cities—on one of Boston’s handful of pleasant blue days, it reflects and multiplies the scudding clouds.”