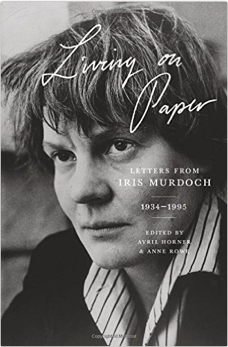

In reviewing Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch, 1934-1995 (Princeton Univ. Press) for the National Post, Robert Fulford cited John Updike prominently. His review begins,

In reviewing Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch, 1934-1995 (Princeton Univ. Press) for the National Post, Robert Fulford cited John Updike prominently. His review begins,

“Dame Iris Murdoch, a much-admired novelist for several decades, was also a bold sexual adventuress. Perhaps she was a love addict before that term was popularized in the 1970s (and with it the 12-step program, Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous). She had many lovers and a close attention to sex was crucial in her life and art.

“According to John Updike, love was for Murdoch what the sea was for Joseph Conrad and war was for Ernest Hemingway. Updike considered her the leading English novelist of her time and believed she learned the human condition through her relationships. Her tumultuous love life, he wrote, was ‘a long tutorial in suffering, power, treachery, and bliss.’ Updike believed that in reading her novels he could feel the ideas, images and personalities of her life pouring through her.”