If your pet peeves include people who speak the language with little regard for or knowledge of correctness, you might be interested in a Jan. 10 Quillette article by Bruce Gilley on “Guarding the Gates of Our Language; One hundred years after the publication of Fowler’s ‘Dictionary of Modern English Usage,’ it is more important than ever to uphold standards of correct English.”

If your pet peeves include people who speak the language with little regard for or knowledge of correctness, you might be interested in a Jan. 10 Quillette article by Bruce Gilley on “Guarding the Gates of Our Language; One hundred years after the publication of Fowler’s ‘Dictionary of Modern English Usage,’ it is more important than ever to uphold standards of correct English.”

Of course, “America’s Man of Letters,” as William Pritchard dubbed him, was cited. John Updike, the master stylist and a precise practitioner of the language, was apparently involved in a kerfuffle involving his beloved New Yorker:

“Most surprising, perhaps, is the enduring allegiance to Fowler at The New Yorker, citadel of oppressed writers, and writers on oppression, in modern American letters. In a curtain-raiser in September 2025 for the Fowler centenary, the University of Delaware academic Ben Yagoda traced the inextricable links between the magazine, launched in 1925, and Fowler, almost as if the magazine was founded as a sort of Society for the Propagation of the Fowler in the United States. In one telling anecdote culled from the magazine’s archives, Yagoda found that the young John Updike, while studying at Oxford in 1954, had submitted a poem to the magazine that was caught up in a minor storm of editorial debate on punctuation according to Fowler. Updike bowed before the strictures, and his corrected poem was published later that year. Thereafter, he seems to have become Keeper of the Fowler at The New Yorker. His scathing review of Burchfield’s 1996 desecration is a monument to fine English sensibilities in the New World. ‘It has the charm, in this age of cultural diversity and politically correct sensitivity, of assuring all users of English that no intelligible usage is absolutely wrong,’ Updike writes. ‘But it proposes no ideal of clarity in language or, beyond that, of grace, which might serve as an instrument of discrimination.’ That word again.

“As Updike foresaw, the globalisation of English and the radicalisation of the academy mean that the need for Fowler has become greater not less. ‘The language is a mess, except as scoured and rinsed and hung out to dry by Fowler.’”

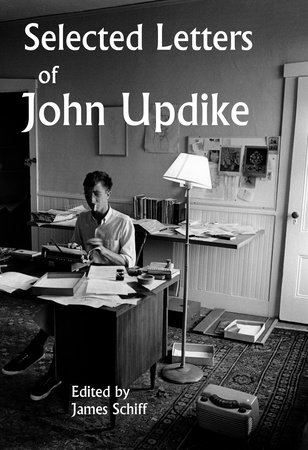

Updike collectors take note: The extensive collection of Michael Broomfield (of Broomfield & De Bellis bibliography fame) is for sale, item-by-item, from

Updike collectors take note: The extensive collection of Michael Broomfield (of Broomfield & De Bellis bibliography fame) is for sale, item-by-item, from  On July 14, 2025, Virginia Pye posted an interview she did with writer Anne Bernays for Cambridge Day: “We had fun.” Bernays is a longtime resident of the Boston area and the author of 10 novels, two books of nonfiction with her husband Justin Kaplan, and a book on the craft of writing with fellow Cambridge author Pamela Painter.

On July 14, 2025, Virginia Pye posted an interview she did with writer Anne Bernays for Cambridge Day: “We had fun.” Bernays is a longtime resident of the Boston area and the author of 10 novels, two books of nonfiction with her husband Justin Kaplan, and a book on the craft of writing with fellow Cambridge author Pamela Painter. John Updike Society president James Plath spent two weeks as a fall 2023 Quarry Farm Fellow working on an essay detailing how Twain modeled being a celebrity writer for both Hemingway and Updike. Plath conducted that research, but also felt compelled to write poems about the house and its inhabitants. Not surprisingly, Updike found his way into one of the poems:

John Updike Society president James Plath spent two weeks as a fall 2023 Quarry Farm Fellow working on an essay detailing how Twain modeled being a celebrity writer for both Hemingway and Updike. Plath conducted that research, but also felt compelled to write poems about the house and its inhabitants. Not surprisingly, Updike found his way into one of the poems: Sometimes the most interesting takes on an author come from great thinkers outside the field of literature. Such is the case with an article by Kali DuBois that was published in Medium:

Sometimes the most interesting takes on an author come from great thinkers outside the field of literature. Such is the case with an article by Kali DuBois that was published in Medium:  The remaining letters are directed to various editors, his parents (whom he addresses as “Plowvillians”), and others that collectively give some sense of his relationship with The New Yorker. The final letter, addressed to fiction editor Deborah Treisman, is a poignant one, given that it was written just 17 days before Updike passed away:

The remaining letters are directed to various editors, his parents (whom he addresses as “Plowvillians”), and others that collectively give some sense of his relationship with The New Yorker. The final letter, addressed to fiction editor Deborah Treisman, is a poignant one, given that it was written just 17 days before Updike passed away: