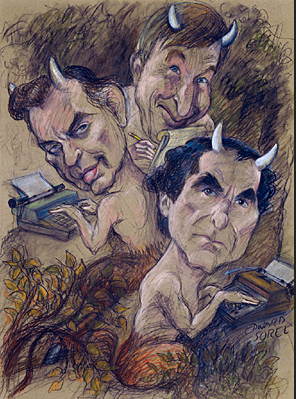

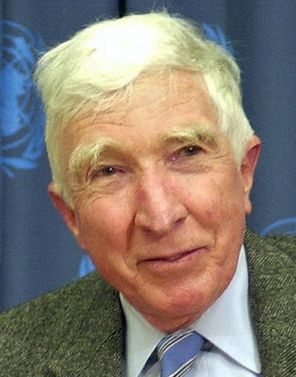

John Updike’s two Time magazine cover portraits are in the National Portrait Gallery, but he’s also depicted on The Laureates of the Lewd, a 1993 pastel by Edward Sorel that was created as an original illustration for a Gentleman’s Quarterly article.

From the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution website:

“Sorel’s three roguish satyrs—Gore Vidal, John Updike, and Philip Roth—were gamboling around the literary landscape making mischief and money in the late 1960s. As James Atlas pointed out in his Gentleman’s Quarterly article “The Laureates of the Lewd,” Updike’s 1968 book Couples, followed by Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge and Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint brought the literary side of the Sexual Revolution to a new level of uncensored candor. American erotic life was out in the open again, in all its complexity and variety. But these books were as much about disillusionment as sex, reflecting the turmoil of generational conflict, a revolution in birth control, a controversial war, protests, assassinations, and race riots. Roth himself noted that if Portnoy’s Complaint had not appeared at the end of a decade ‘marked by blasphemous defiance of authority and loss of faith in the public order, I doubt that a book like mine would have achieved such renown in 1969.'”