John Updike’s children recently donated more one-of-a-kind objects to The John Updike Childhood Home & Museum, among them two still life paintings that their father and mother had painted side-by-side while Updike was a student at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford, England. Michael Updike said that as a trailing spouse who majored in art as an undergrad, his mother talked her way into sitting in and participating in John’s classes. Mary sat to his father’s right, Michael pointed out, given the placement of objects on each canvas. The paintings are referenced in Updike’s short story “Still Life” (from Pigeon Feathers, reprinted in The Early Stories):

“At the greengrocer’s on Monday morning they purchased still life ingredients. The Constable School owned a great bin of inanimate objects, from which Leonard had selected an old mortar and pestle. His idea was then to buy, to make a logical picture, some vegetables that could be ground, and to arrange them in a Chardinesque tumble. But what, really, was ground, except nuts? The grocer did have some Jamaican walnuts.

“At the greengrocer’s on Monday morning they purchased still life ingredients. The Constable School owned a great bin of inanimate objects, from which Leonard had selected an old mortar and pestle. His idea was then to buy, to make a logical picture, some vegetables that could be ground, and to arrange them in a Chardinesque tumble. But what, really, was ground, except nuts? The grocer did have some Jamaican walnuts.

“Don’t be funny, Leonard,” Robin said. “All those horrid little wrinkles, we’d be at it forever.”

“Well, what else could you grind?”

“We’re not going to grind anything; we’re going to paint it. What we want is something smoothe.”

“Oranges, miss?” the lad in charge offered.

“Oh, oranges. Everyone’s doing oranges—looks like a pack of advertisements for vitamin C. What we want…” Frowning, she surveyed the produce, and Leonard’s heart, plunged in the novel intimacy of shopping with a woman, beat excitedly. “Onions,” Robin declared. “Onions are what we want.”

John gave his still life to his mother, who displayed it at the Plowville house, while Mary kept hers. Now the paintings are together again, above the bed that John painted with his mother—John’s on the left, Mary’s on the right . . . just as in Oxford.

Visit and look at the paintings up close and vote: Who did it best? John (left) or Mary (right)?

The John Updike Childhood Home & Museum, 117 Philadelphia Ave. in Shillington, Pa., is owned and operated by the 501c3 John Updike Society. It is open most Saturdays from 12-2 p.m. For questions about visiting the museum, contact director Maria Lester, johnupdikeeducation@gmail.com.

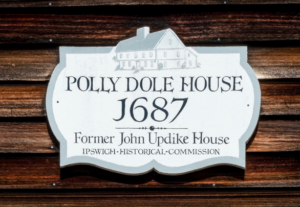

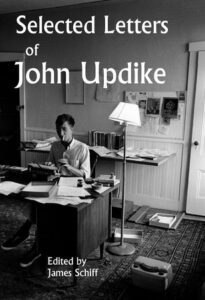

Michael Updike has been touring to promote Selected Letters of John Updike—as his father would have done, were he still with us. Interest in Updike has remained high in Ipswich, where the Updike’s lived for many years and where he wrote in an office on the second floor of the Caldwell Building.

Michael Updike has been touring to promote Selected Letters of John Updike—as his father would have done, were he still with us. Interest in Updike has remained high in Ipswich, where the Updike’s lived for many years and where he wrote in an office on the second floor of the Caldwell Building.

“At the greengrocer’s on Monday morning they purchased still life ingredients. The Constable School owned a great bin of inanimate objects, from which Leonard had selected an old mortar and pestle. His idea was then to buy, to make a logical picture, some vegetables that could be ground, and to arrange them in a Chardinesque tumble. But what, really, was ground, except nuts? The grocer did have some Jamaican walnuts.

“At the greengrocer’s on Monday morning they purchased still life ingredients. The Constable School owned a great bin of inanimate objects, from which Leonard had selected an old mortar and pestle. His idea was then to buy, to make a logical picture, some vegetables that could be ground, and to arrange them in a Chardinesque tumble. But what, really, was ground, except nuts? The grocer did have some Jamaican walnuts.