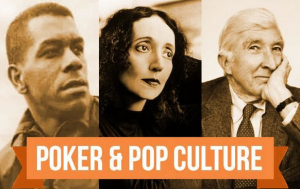

Writing for Poker News, Martin Harris compiled a fun article on “Poker & Pop Culture: Fiction Writers Finding Truth in the Cards.” In it, he highlights stories by William Melvin Kelley, Joyce Carol Oates, and John Updike—the latter, under the heading “Poker as an Escape (For a While, Anyway).”

“Best remembered for a quartet of novels (plus one novella) tracing the life of Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, starting with 1960’s Rabbit, Run, John Updike penned more than 20 novels, hundreds of short stories, several books of poetry, and a significant amount of literary criticism and essays. Like both Kelley and Oates, Updike is often praised for his descriptive powers and ability to portray characters and scenes in affecting ways, providing genuinely deep insight into our existence when his plots involve relatively ordinary, ‘day-to-day’ scenes and situations.

“Updike’s story ‘Poker Night’ (published in Esquire in 1984 and later collected in Trust Me) presents an unnamed, middle-aged male narrator living a very familiar, not too remarkable-seeming existence. He’s married with two children (now grown), has worked many years at ‘the plant,’ and for three decades has been part of an every-other-Wednesday poker game.

“Updike’s story ‘Poker Night’ (published in Esquire in 1984 and later collected in Trust Me) presents an unnamed, middle-aged male narrator living a very familiar, not too remarkable-seeming existence. He’s married with two children (now grown), has worked many years at ‘the plant,’ and for three decades has been part of an every-other-Wednesday poker game.

“After working late one Wednesday the narrator has a doctor’s appointment from which he goes straight to the poker game. However, on this day the doctor introduces a disruption to the man’s routine. The diagnosis isn’t specified, but talk of chemotherapy and treatments makes it clear enough the man has cancer, and that his prospects going forward are grave.

“Much of the rest of the story finds the man playing his poker game as usual, putting his diagnosis (and the thought of telling his wife about it) to the side for a few hours while letting the lively card game literally distract him from thinking too directly about his own mortality.

“He rattles off the backgrounds of that night’s players — Bob, Jerry, Ted, Greg, and Rick — giving the history of the game and how over thirty-plus years ‘the stakes haven’t changed,’ remaining low enough to keep the game fun. ‘It really is pretty much relaxation now, with winning more a matter of feeling good than the actual profit,’ he explains.

“The game produces a few interesting hands, including a couple of instances when the narrator believes he made mistakes — staying in one hand, and folding another when only to find out he was best. ‘It’s in my character to feel worse about folding a winner than betting a loser,’ he comments, adding how the latter ‘seems less of a sin against God or Nature or whatever.’

“It’s clear the game is providing a kind of escape for him, and Updike deftly has him recognize a kind of symbolism in the cards themselves.

“‘The cards at these moments when I thought about it seemed incredibly, thin: a kind of silver foil beaten to just enough of a thickness to hide the numb reality that was under everything,’ he says.

“He notices the others around the table, friends whom he’s known for many years, and finds himself recognizing how they have aged. Suddenly he thinks about death again, and earns a small measure of comfort in the idea that ‘people wouldn’t mind which it was so much, heaven or hell, as long as their friends went with them.’ The thought has the effect of winning a small pot, carrying him forward a little further.

“He finishes the game five bucks down, though when he gets home he tells his wife ‘I broke about even.’ It’s a small lie, though it mirrors a larger one he’d been telling himself ever since getting the news from his doctor — namely, that somehow it wasn’t as bad as it sounded, and that perhaps everything would work out okay.

“He knows this is a lie, though. The short scene with his wife confirms it, and the story ends with the narrator recognizing in his wife’s look that she’s contemplating life without him. The description sounds a lot like a player having finally noticed an opponent’s tell, thereby learning something important about what might come next.

“‘You could see it in her face her mind working,’ he says. ‘She was considering what she had been dealt; she was thinking how to play her cards.'”

Harris is the author of the forthcoming Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America’s Favorite Card Game and a professor at UNC-Charlotte who teaches a course on Poker in American Film and Culture.