Updike criticism over the past several decades has gravitated toward the Rabbit tetralogy. In Imagination and Idealism in John Updike’s Fiction (Camden House, 2017, cloth, 228pp.), Michial Farmer bucks that trend, leaving Rabbit out of his discussion entirely. Given Updike’s exhaustive (and exhausting) oeuvre, it’s no surprise that, despite the broad title, only a handful of novels make the cut for Farmer’s exploration of Updike and the imagination.

Updike criticism over the past several decades has gravitated toward the Rabbit tetralogy. In Imagination and Idealism in John Updike’s Fiction (Camden House, 2017, cloth, 228pp.), Michial Farmer bucks that trend, leaving Rabbit out of his discussion entirely. Given Updike’s exhaustive (and exhausting) oeuvre, it’s no surprise that, despite the broad title, only a handful of novels make the cut for Farmer’s exploration of Updike and the imagination.

As the back cover note summarizes, Farmer “argues that, while the imagination is for Updike a means of human survival and a necessary component of human flourishing, it also has a destructive, darker side, in which it shades into something like philosophical idealism. Here the mind constructs the world around it and then, unhelpfully, imposes this created world between itself and the ‘real world.’ In other words, Updike is not himself an idealist but sees idealism as a persistent temptation for the artistic imagination.”

In a first chapter, “John Updike and the Existentialist Imagination,” Farmer posits that while Updike “cannot endorse Sartre’s atheism or the nihilism that lurks just beyond his celebration of humanity’s radical freedom,” he nonetheless “uses Sartrean metaphysics as a jumping-off point for his own, more Kierkegaardian, reflections.” The fullest discussion of the latter remains David Crowe’s recent study, but for the intended purpose of this volume Farmer does a nice job of setting the stage for a study of the imaginative nature of Updike’s work, weighing Sartre’s suggestion that the human imagination, “and in particular the aesthetic imagination—can be a way to fight against meaninglessness.”

According to Farmer, Updike’s “job as a fiction writer” is to “use his powerful imagination, and the language that makes up its currency, to falsify the material world” that exists in opposition to the self and “bestow on it an order that does not properly speaking belong to it, but in bestowing that order to preserve and re-present it. The imagination thus counts among the highest and most important human faculties,” Farmer writes.

In the 15 chapters that follow, Farmer treats Updike’s works loosely chronologically but also finds a way to order them topically with the aid of a five-part section structure:

- The “Mythic Immensity” of the Parental Imagination

- Collective Hallucination in the Adulterous Society

- Imaginative Lust in the Scarlet Letter Trilogy

- Female Power and the Female Imagination

- The Remembering Imagination

Regarding what he calls the “parental imagination,” Farmer argues, “Mothers, in Updike’s early fiction, tend to create imaginative worlds for their sons to live in, and these worlds, when confronted with the world of mere things, tend to crush the sons for whom they were created.” That’s a big claim, and the chapters supporting it are probably the most enticing to consider, yet also the most elusive—especially when Farmer at times seems to conflate “force of will” with “force of imagination.” Still, his analyses of “Flight,” “His Mother Inside Him,” “Ace in the Hole,” “A Sandstone Farmhouse,” “The Cats,” The Centaur, and Of the Farm are engaging.

The chapters themselves read like brief imaginative essays: a combination of scholarship and readability that’s well reasoned and written in such a way as to anticipate reader questions. As a result, the author, while discussing texts that would be familiar to most Updike scholars and aficionados, confidently proceeds without feeling the need to cite a tremendous amount of secondary sources—only those that seem necessary to him. Some scholars may see that as a negative. Nowhere near all of the secondary sources for Updike’s Scarlet Letter trilogy, for example, are cited. Yet, underlying his arguments, Farmer demonstrates an awareness of the range of Updike scholarship throughout his chapter discussions, quoting from both the very first monograph (the Hamiltons) and the most recent one (Crowe).

Some of Farmer’s arguments have an “of course” feel to them, perhaps because the chapters’ arguments are compressed and proceed so methodically—with just enough theoretical grounding, contextual references, and examples from Updike’s works to lead readers to what feels like a foregone conclusion. Sometimes it’s a slightly new twist on familiar theory. For example, Updike’s oft-stated intent “’to transcribe middleness with all its grits, bumps, and anonymities, in its fullness of satisfaction and mystery,’ is,” Farmer writes, “in part a method of keeping the human imagination honest: we may not be able to have perfect access to the material world, but the material world periodically, perhaps even constantly, makes itself known by tearing down the imagination constructions we build on its back. The author’s fidelity to the world is thus held in dialectical tension with his imaginative project; the two are always in dialogue, and the human self is always moving between the two of them—forever building, forever destroying.” Mostly, it’s the attention paid to works that are too often ignored by other scholars that’s refreshing.

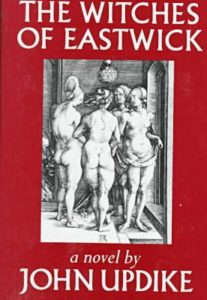

In the “adulterous society” section Farmer discusses “Man and Daughter in the Cold,” “Giving Blood,” “The Taste of Metal,” “Avec la Bébé-Sitter,” “The Hillies,” Marry Me, and Couples; in addition to The Witches of Eastwick, for the section on female power he considers “Marching through Boston,” “The Stare,” “Report of Health,” “Living with a Wife,” and “Slippage”; and in the final section he draws on examples from Memories of the Ford Administration, “In Football Season,” “First Wives and Trolley Cars,” “The Day of the Dying Rabbit,” “Leaving Church Early,” and “The Egg Race,” in addition to the more frequently discussed “The Dogwood Tree,” “A Soft Spring Night in Shillington,” and “On Being a Self Forever.”

One of this book’s strengths is that does manage to reconsider old concepts in the pursuit of new, and to explore a satisfying range of critical, theoretical, and philosophical arguments without insulting the intelligence of those readers who might already know the terms and their meanings. That kind of writing is hard to pull off, yet the author manages to do so with grace. As a result, Imagination and Idealism in John Updike’s Fiction is an easy read—one of the more engaging and accessible monographs on an author that I’ve encountered in recent years. It holds appeal not only for Updike scholars, but also for readers with more than a casual interest in Updike. This book helps readers to appreciate the sometimes erratic or unexplainable behavior of many of Updike’s characters, who live in worlds partially created by their own vivid and often conflicted imaginations.

Reviewed by James Plath