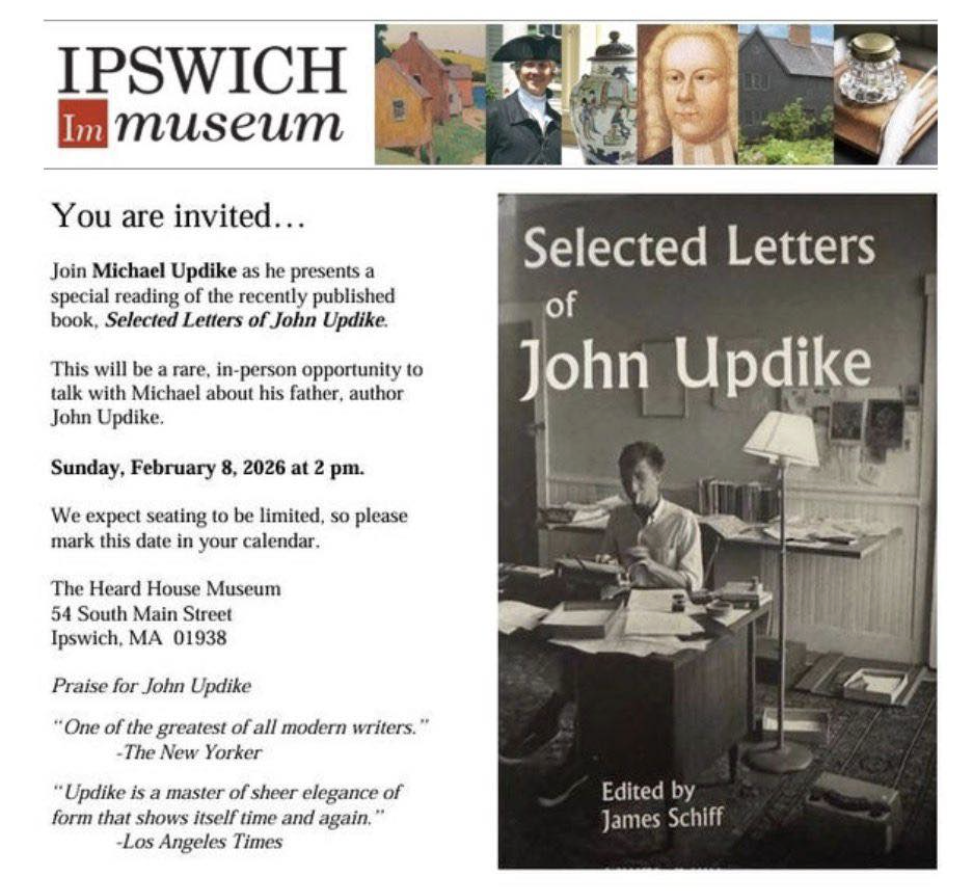

Trevor Meek, of The Local News (Ipswich, Mass.), published a Jan. 31, 2026 piece on the Selected Letters of John Updike that began,

“Living in Ipswich in the 1960s and ’70s with John Updike as a neighbor meant playing a high-stakes game of literary roulette. “On any given day, you might crack open his newest novel or short story to discover you’d been immortalized — or perhaps skewered — on a page destined to be read by millions around the world. “That uneasy thrill returned for some folks late last year with the release of Selected Letters of John Updike.

“’Even with this book, various people are looking through it to see if they’re mentioned,’ said Updike’s son, Michael, a sculptor. “’And then when they realize they are mentioned, they’re insulted,’ he added with a laugh.”

Michael Updike, heavily quoted in the article, defended his father against one of the most common charges. “He seems to be an author who is judged as a misogynist because some of his characters are selfish. . . . We don’t say Nabokov is a pedophile because his character Humbert Humbert is one in Lolita.”

Michael Updike told The Local News that he’s working on the release of his father’s unpublished novel, Home. “We’re still figuring out how to get that rolling,” he said.

Michael Updike told The Local News that he’s working on the release of his father’s unpublished novel, Home. “We’re still figuring out how to get that rolling,” he said.

We asked Michael (pictured) for more details, and here’s what he had to say:

“Chris Carduff [who edited several of Updike’s Library of America volumes] gave us the idea, saying it was a completed novel albeit rejected by a publishing house. Jim Schiff [editor of the Selected Letters] has read it and says it’s not a perfect novel but does have a lot of new material about my grandmother in it. Andrew Wylie has been sent a copy and he thinks it should be published. So much of it is hand written, and our first step is to find a good typist who will type it up in Word. Then an editor to comb out any redundant or rough spots, and Wiley will shop it around. No timeline, but hopefully soon, by publishing terms—two or three years.”

Updike didn’t talk much about Home with interviewers, but he did tell Eric Rhode in 1969, ” I had written, prior to [The Poorhouse Fair], while living in New York City, a 600-page novel, called, I think, Home, and more or less about myself and my family up to the age of 16 or so. It had been a good exercise to write it and I later used some of the material in short stories, but it really felt like a very heavy bundle of yellow paper, and I realized that this was not going to be my first novel—it had too many traits of a first novel. I did not publish it, but I thought it was time for me to write a novel.”

If Home is as heavily autobiographical as Updike suggests, perhaps it will be read and appreciated as a companion to his Self-Consciousness: Memoirs (1989).

The remaining letters are directed to various editors, his parents (whom he addresses as “Plowvillians”), and others that collectively give some sense of his relationship with The New Yorker. The final letter, addressed to fiction editor Deborah Treisman, is a poignant one, given that it was written just 17 days before Updike passed away:

The remaining letters are directed to various editors, his parents (whom he addresses as “Plowvillians”), and others that collectively give some sense of his relationship with The New Yorker. The final letter, addressed to fiction editor Deborah Treisman, is a poignant one, given that it was written just 17 days before Updike passed away: One of the

One of the