In a Culture segment for Five Books, novelist Ian McEwan “talks about the books that have helped shape his own—from the biography of a scientific genius to a treatise on the end of time—and the importance of finding ‘mental freedom.'”

In a Culture segment for Five Books, novelist Ian McEwan “talks about the books that have helped shape his own—from the biography of a scientific genius to a treatise on the end of time—and the importance of finding ‘mental freedom.'”

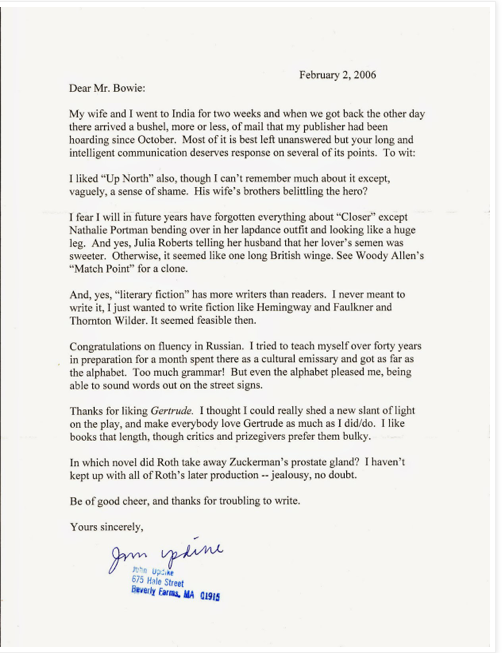

Here are the exchanges having to do with the Updike influence:

Would you go to Updike for sex, if not Larkin?

I think some of the descriptions of sex in Updike are extraordinary. I could never follow him down his route because his gift is one I’ve never hoped to emulate, which is the visual. In a sense he almost debunks or destroys the thing he’s describing, because of his clinical eye, but it does take my breath away. In this realm he’s a master of the hyper-real.

Talk a little about John Updike if you will, who died not long ago, in 2009. Your third book is Rabbit at Rest, the fourth of his ‘Rabbit’ novels.

Updike has been a very important writer for me, the one I’ve admired most, read most, and returned to most often. I was deeply touched by his death. I felt that we had conversations unfulfilled – we got to know each other a little in the last six or seven years of his life, and we had a correspondence.

What was he like, his character?

He was impenetrably courteous. At first, quite difficult to get beyond his very gentlemanly, polite and considerate shell. He protected himself. Behind this shell was all of his work. It was easier to get a more intimate Updike by writing letters. If I wrote, I’d get a response by return of post, apologising for being so quick, just as I would be apologising for my delayed replies. He said it was the only way he could keep his desk clear. But of course it was not that at all. This was a highly organised mind with boundless creative energy. He could turn in 1200 words of fiction in a day, write a review or an essay, and still address his correspondence.

You’ve called him ‘the greatest novelist writing in English at the time of his death’. What is it about Updike that deserves that praise?

Great sentence-maker; extraordinary noticer; wonderful eye for detail; great fondler of details, to use Nabokov’s phrase. Huge comic gift, finding its supreme expression in the Bech trilogy. A great chronicler, in the Rabbit tetralogy, of American social change in the 40 years spanned by those books. Ruthless about women, ruthless about men. (Feminists are wrong to complain. There’s a hilarious streak of misanthropy in Updike). He reminds us that all good writing, good observation contains a seed of comedy. A wonderful maker of similes. His gift was to render for us the fine print, the minute detail of consciousness, of what it’s like in a certain moment to be another person, to inhabit another mind. In that respect, Angstrom will be his monument.

You say feminists are wrong to criticise him, but there is that criticism – that he has a ‘male gaze’. Do you face the same challenges when you write female characters?

I have done occasionally. It means nothing to me. This is a visual form. Remember Conrad’s exhortations in the preface to The Nigger of the Narcissus: ‘I am trying…by the power of the written word…to make you see.’

Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom was, I gather, an inspiration for Michael Beard, the protagonist of Solar?

I crouched in Updike’s shadow. I set myself the problem of having an unsympathetic hero, and enticing a reader to stay in his company for the length of a novel. With Rabbit, Updike showed us how this is achieved. Rabbit is not the nicest of men, his is a narrow consciousness, he’s of limited education, deeply ungenerous in the private life – remember how he makes love to his son’s wife? Grumpy, irritable, bigoted in some respects, and yet somehow Updike succeeds in making him the prism through which 40 years of American social change is observed, and 40 years of close shifts within family relations, adulterous affairs and the tragedy of a lost child.

How does he do this? Well, he invents an altered or heightened realism. He gives Rabbit his own – Updike’s – thoughts, and yet somehow he makes them plausibly Rabbit’s. Rabbit has reflections on mortality that could only be, in any realistic frame, Updike’s. But he makes them Rabbit’s; he shoehorns them into this limited mental space. It’s a rhetorical trick. In short, what Updike succeeds in doing is to make Rabbit interesting. He might not be good, but he’s interesting, and we travel with him for that reason alone. I can’t claim for a moment to have come anywhere near this with Michael Beard, but that was the example at my side.

When I feel my faith flagging in the whole enterprise of fiction – and all writers experience this – a few pages of Updike will restore my energies and optimism.

“Ian McEwan recommends Books That Have Helped Shape His Novels”

Rosanna Greenstreet of The Guardian recently played 23 questions with novelist Ann Patchett, whose novels The Magician’s Assistant, Bel Canto, and State of Wonder were shortlisted for the Orange Prize for Fiction (now the Women’s Prize for Fiction), and this interesting exchange popped up:

Rosanna Greenstreet of The Guardian recently played 23 questions with novelist Ann Patchett, whose novels The Magician’s Assistant, Bel Canto, and State of Wonder were shortlisted for the Orange Prize for Fiction (now the Women’s Prize for Fiction), and this interesting exchange popped up: