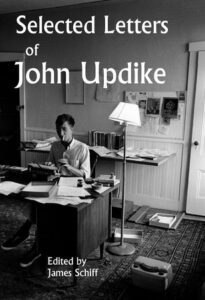

James Schiff, vice president of The John Updike Society and editor of The John Updike Review, gave a great interview to Charles McElwee on The Real Clear Pennsylvania Podcast. Schiff, a professor of English at the University of Cincinnati, talked about the Selected Letters of John Updike, which Schiff also edited and the debut of which the Updike Society celebrated in New York City in October 2025.

Category Archives: Interviews

Editor Schiff and Updike siblings interviewed about the Selected Letters

In his introduction to an interview he conducted with James Schiff, Joe Donahue wrote, “John Updike remains one of the most admired and prolific voices in American Literature. Over five decades he produced novels, short stories, poems, criticism, and essays that examine faith and art, desire, and the American experience in all its complexity. . . . Now in the new book ‘Selected Letters of John Updike’ editor James Schiff offers readers a window into that private world drawing from decades of correspondence. Schiff presents a portrait of Updike as both craftsman and confidante, generous, witty, and endlessly reflective about writing and life.”

In his introduction to an interview he conducted with James Schiff, Joe Donahue wrote, “John Updike remains one of the most admired and prolific voices in American Literature. Over five decades he produced novels, short stories, poems, criticism, and essays that examine faith and art, desire, and the American experience in all its complexity. . . . Now in the new book ‘Selected Letters of John Updike’ editor James Schiff offers readers a window into that private world drawing from decades of correspondence. Schiff presents a portrait of Updike as both craftsman and confidante, generous, witty, and endlessly reflective about writing and life.”

Here’s the link to the WAMC Northeast Public Radio podcast.

More conversation about John Updike and the letters comes from a Radio Open Source interview with Michael Updike and Miranda Updike conducted by Christopher Lydon, a Boston-area fixture who interviewed John Updike on numerous occasions. In sending the link to the Updike siblings, Lydon wrote, “We want you to take a bow… and enjoy this piece as we do! You and Michael are heroic here, and funny and deep… And we all fall in love with your marvelous dad, all over again.”

Here’s the link to “John Updike’s Vocation.”

If you haven’t gotten a copy of the book yet, here’s a link to order from Bookshop.org, where every purchase supports local independent bookstores.

Writer Anne Bernays recalls Updike in an interview

On July 14, 2025, Virginia Pye posted an interview she did with writer Anne Bernays for Cambridge Day: “We had fun.” Bernays is a longtime resident of the Boston area and the author of 10 novels, two books of nonfiction with her husband Justin Kaplan, and a book on the craft of writing with fellow Cambridge author Pamela Painter.

On July 14, 2025, Virginia Pye posted an interview she did with writer Anne Bernays for Cambridge Day: “We had fun.” Bernays is a longtime resident of the Boston area and the author of 10 novels, two books of nonfiction with her husband Justin Kaplan, and a book on the craft of writing with fellow Cambridge author Pamela Painter.

When Pye asked Bernays, “But you say Cambridge as a literary center hasn’t really fed you or your work over the years?” Bernays responded,

“I’m very gregarious, as you can tell, and I enjoy meeting people. I love talking to people and when there was no community, I and two other people, we decided to form one here. And soon after that one of them moved away and the other person lost interest, so I was left with founding Pen New England, which I ran for 10 years. I was the head of the board and I had some of my friends on it. Nobody wanted to do it. That’s often how it is, but people came to the panels we put on.

“My favorite one was called, ‘Rejection.’ John Updike, who was a friend, I got him to come on. And all these people were there, including Leslie Epstein, talking about rejection. When John Updike talked about rejection there was this gasp from the audience. It was the best thing that could have happened because people came up to me afterwards and said, ‘John Updike was rejected?’ It made the process less awesome, less scary. We had fun.”

Serbian scholar tells interviewer Updike remains relevant

ALA, Chicago, 2022

John Updike Society board member Biljana Dojčinović was recently interviewed by Charles Carlini of Casa Carlini publishing, who wished to confront the difficult questions underlying why Updike seems less read these days. “Did the sheer brilliance of his style mask a certain thematic narrowness? Were his lush sentences and psychological insights ultimately confined to the worldview of a privileged few? Such questions have sparked fresh debate about his rightful place in the literary canon.

“One of the sharpest voices in this conversation is Biljana Dojčinović, a scholar whose work pushes beyond easy categories. A professor of literary studies with expertise in Anglo-American modernism, Dojčinović brings a distinctly transnational lens to Updike’s fiction, interrogating how his narratives handle (or mishandle) issues of gender, power, and identity. Rather than slotting him neatly into the roles of either misunderstood genius or emblem of patriarchal excess, she urges readers to sit with the contradictions—those moments where Updike is most dazzling, and most troubling.”

Dojčinović cautioned, “When it comes to biases, we need to be careful not to confuse the author with his characters, nor with the assumptions and prejudices we ourselves bring to the reading experience.”

“It’s no coincidence that all great literary works are, in some way, critical of the times they depict,” Dojčinović said. “When a writer speaks from a certain distance, it creates space for us to reflect on what we’re reading. In the modernist style, there’s no guiding authorial voice—it’s up to us to decide what’s right or wrong. That can be challenging; irony, for instance, is often missed. And when that happens, the meaning of a work can be lost entirely.”

Asked how readers should “reconcile historical context with present-day critiques,” Dojčinović responded, “When we read literature from earlier periods—or even from different cultures—we need to stay mindful of the contextual differences. More than that, we should make an effort to learn about those contexts. Take slang, for example—it’s clear we shouldn’t apply contemporary meanings to a title like The Turn of the Screw by Henry James. And yet, we often impose our present-day values and interpretations onto works from the past or from unfamiliar cultures. That’s where many misunderstandings begin.”

1966 interview shows Updike in Ipswich

A 1966 interview, “John Updike: ‘One way to make a living that didn’t necessarily inflict pain on other people,'” is available to watch now on YouTube. Some of the questions overlap the Life magazine interview, so odds are it’s connected somehow. There’s a lot of footage of Updike and his young family inside the house and in the yard.

Christopher Lydon considers John Updike’s ‘Terrorist’

Boston radio’s Christopher Lydon has interviewed Updike on numerous occasions, and now he’s turned his admiration for Updike into “Open Source” conversations. In “John Updike and his Terrorist,” Lydon shares an interview he did with Updike about the post-9/11 novel and adds his own comments:

“Terrorist is cinematic and political—wonderfully so, as I read it. It may be as close to the movie Syriana as we’ll ever get from Updike.

“Terrorist is cinematic and political—wonderfully so, as I read it. It may be as close to the movie Syriana as we’ll ever get from Updike.

“It’s not for me to vouch that he nailed every answer here. But I can report the huge pleasure for one reader—picking up a piece of our conversation recently on The Great American Novel—in ‘public’ fiction, masterfully made, encompassing the depressive high-school guidance counsellor Jack Levy, and the hateful Secretary of Homeland Security, whose name sounds like Haffenreffer; and at the center of it all, Ahmad Ashmawy Mullow at the brink of manhood, flickering between earnestness and extremism, trying to solidify a Muslim consciousness in what feels like a wasteland of selfishness and materialism.'”

On January 28, 2009, one day after Updike died, Lydon had paid tribute to the legendary writer who chose the Boston area for his home for his adult life, in “John Updike: Ted Williams of Our Prose”: “John Updike had every kind of grace about him, including for me an aura of divine blessing. I liked his religious inquiries better than the Rabbit books—novels like A Month of Sundays, Roger’s Version, and In the Beauty of the Lilies, and of course stories like ‘Pigeon Feathers’ about a boy’s crisis of faith, which ends in his famous meditation on the pigeons he’s shot, on orders, in his mother’s barn, and the irresistible beauty of the blue and gray patterns in their dull coloring.”

Washington Post book critic looks back, recalls Updike and others

Today’s Washington Post featured a Q&A, “Post critic Michael Dirda turns a page: Dirda discusses the life of a critic, and his decision for a change of pace after 30 years of weekly columns,” in which John Updike merited a brief mention.

Today’s Washington Post featured a Q&A, “Post critic Michael Dirda turns a page: Dirda discusses the life of a critic, and his decision for a change of pace after 30 years of weekly columns,” in which John Updike merited a brief mention.

Asked if he has a favorite instance of when one of his reviews led to correspondence with the book’s author, Dirda responded, “In general, I avoided getting to know authors I admired because then I’d have to recuse myself from reviewing their books. Still, I counted James Salter and Tom Disch as good friends, was something of a gossipy pen pal with A.S. Byatt, and enjoyed many long telephone conversations with Angela Carter. Among the best six or seven hours of my adult life were those I spent talking books and writers with Guy Davenport at his home in Lexington, Kentucky. I was also gobsmacked when John Updike sent me a two-page letter complimenting me about my memoir, An Open Book.

Nobel laureate cites Updike influence

Turkish novelist and playwright Orhan Pamuk, who was awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature, is now his country’s best-selling and most prominent writer. His books have sold more than 13 million copies internationally, with Snow, a novel that captures the sociopolitical milieu of 21st-century Turkey, drawing extra attention for its narrator, whom readers are meant to interpret as Pamuk himself.

Pamuk talked with The Saturday Paper writer Amal Awad about his most recent novel, Nights of Plague, which he began before the pandemic and which Awad described as a “historical murder mystery set on the imaginary Mediterranean island of Mingheria during an epidemic” of bubonic plague, adding “it’s Pamuk’s Moby-Dick, weighing in at nearly 700 pages.”

During their interview, Awad said that they talked “about criticism—both literary and hate speech—how the Turkish media is full of people expressing their hatred of him. ‘They haven’t read anything [I’ve written] and I’m proud to say that,’ Pamuk says, laughing. ‘If a literary criticism hurts, there are two criteria. One, it damages economically, the book won’t sell; that is very bad. And the other is you actually have a high opinion of this person and you want his approval.’

“Pamuk rarely worries about the latter nowadays,” Awad wrote, “but he says he has benefited from literary criticism and acknowledgment from his elders throughout his life. ‘John Updike made me famous in the United States,’ he says. ‘A critic who is 30 years older than me, made me in Turkey. There’s always been good, nice critics.'”

Read the whole article.

McEwan talks about the assault on Rushdie and on literary reputations

Lisa Allardice recently interviewed Ian McEwan for The Guardian (“Ian McEwan on ageing, legacy and the attack on his friend Salman Rushdie: ‘It’s beyond the edge of human cruelty'”). The occasion was the release of Lessons, the new novel by McEwan, who was the keynote speaker at the 5th Biennial John Updike Society conference at the University of Belgrade, Serbia.

The nearly 500-page novel, which mentions the fatwa against Rushdie, is “far longer than McEwan’s characteristically ‘short, smart and saturnine’ novels, as John Updike summed up in a 2002 review of Atonement,” Allardice wrote. “McEwan’s ambition with Lessons, his 18th novel, was to show the ways in which ‘global events penetrate individual lives,’ of which the fatwa was a perfect example. ‘It was a world-historical moment that had immediate personal effects, because we had to learn to think again, to learn the language of free speech,’ he says.”

“Billed as ‘the story of a lifetime,’ it is in many ways the story of McEwan’s life. ‘I’ve always felt rather envious of writers like Dickens, Saul Bellow, John Updike and many others, who just plunder their own lives for their novels,’ he explains. ‘I thought, now I’m going to plunder my own life, I’m going to be shameless.'”

“‘I’ve read so many literary biographies of men behaving badly and destroying their marriages in pursuit of their high art. I wanted to write a novel that was in part the story of a woman who is completely focused on what she wants to achieve, and has the same ruthlessness but is judged by different standards,’ he explains. ‘If you read Doris Lessing’s cuttings they will unfailingly tell you that she left a child in Rhodesia.'”

Asked whether, at age 75, he worries about his legacy, McEwan responded, “I’d like to continue to be read, of course. But again, that’s entirely out of one’s control. I used to think that most writers when they die, they sink into a 10-year obscurity and then they bounce back. But I’ve had enough friends die more than 10 years ago, and they haven’t reappeared. I feel like sending them an email back to their past to say, ‘Start worrying about your legacy because it’s not looking good from here.'”

Allardice wrote, “He was greatly saddened by what he describes as ‘the assault on Updike’s reputation’; for him, the Rabbit tetralogy is the great American novel. Saul Bellow, another hero, has suffered a similar fate for the same reasons, he says. ‘Those problematic men who wrote about sex—Roth, Updike, Bellow and many others.'”

“We’ve become so tortured about writing about desire. It’s got all so complex,’ he says. ‘But we can’t pretend it doesn’t exist. Desire is one of the colossal awkward subjects of literature, whether it’s Flaubert you’re reading or even Jane Austen.'”

Read the whole interview.

What author cracks up Jerry Seinfeld? Would you believe John Updike?

An interview with comedian Jerry Seinfeld that originally appeared as a New York Times “By the Book” interview turned up on a number of sites, including a blog by Jack Limpert, editor of The Washingtonian for more than 40 years. Here are some of the exchanges:

Asked if he reads much fiction, Seinfeld said, “When I used to read more, I really loved John Updike and John Irving. Updike, to me, was insane. I love microscopic acuity and I thought he was untouchable in that: the fineness, and the smallness of things that he would describe so well.

What was the last book that made him laugh?

“I don’t really laugh reading books,” Seinfeld said. “It’s pretty hard to laugh when you’re reading—the written word is tough. I mean, the Updike stuff is funny to me. You know, describing the circles of water under someone’s toes when they get out of the pool. That makes me laugh more than anything, that he would zero in on that.”

Which three writers, dead or alive, would he invite to a literary dinner party?

“Well, Updike I mentioned. I think David Halberstam would be a great dinner guest. And I’m into this Marx Brothers thing now, so I would like to sit with this guy [Robert] Bader for dinner. And Lincoln! I consider him to be a great writer.”

What does he plan to read next?

“I’m out of stuff, but along the same lines as John Updike I might give Nicholson Baker a shot.”

Read the whole interview.