In “Revisiting The Witches of Eastwick 330 Years After Salem” for the Chicago Review of Books, Chicago-based writer Sara Batkie writes, “Fifty-odd years ago, covens were the locus of Satanic activity in such movies and books as Rosemary’s Baby and Suspiria. But the rise of second-wave feminism and women in the workforce in the late ’70s and early ’80s gave way to a gentler, more domestic spellcaster, a trend arguably initiated by John Updike’s 1984 novel The Witches of Eastwick and the film adaptation three years later.”

After giving credit where she thinks credit is due, Batkie offers a refrain that’s familiar to Updike readers: “Most of his previous work was steeped in middle class realism, bound by such earthly concerns as which friend’s wife to sleep with and the masculine urge to escape from familial obligations. The inner lives of women were not often foregrounded, to put it generously, though Updike was one of our most skilled sensualists, and it’s clear he admired the ‘fairer sex,’ even if he didn’t always understand them.”

Batkie suggests that maybe Updike added witchcraft to his first real attempt to write about the inner lives of women in order to “hedge his bets. If something didn’t ring true to his female readership, it could be attributed to the three women’s unique powers.”

Batkie gives the film higher marks than the novel when 2022 feminism is the standard, but concludes, “So where does that leave us today, post-third-wave and likely post-Roe? Though neither Updike nor [director George] Miller set out to predict our fracturing present, both versions of The Witches of Eastwick now feel like a warning, or at least a precaution. Magic has its limits, both personally and politically. A woman’s right to bodily autonomy is no longer a fringe belief, no matter what men in power like Alito might think.”

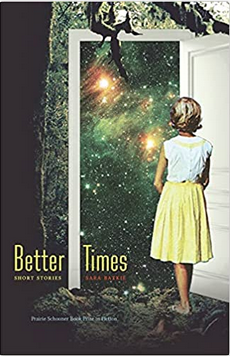

Batkie is the author of Better Times: Short Stories, which won the 2017 Raz/Shumaker Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction. Read her whole Chicago Review of Books essay here.