Scott Simon on NPR’s Simon Says today opined that “Blistering summers are the future,” and backs that up with equally frightening claims from the United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization: “there is more lethal heat in our future because of climate change caused by our species on this planet. Even with advances in wind, solar and other alternative energy sources, and international pledges and accords, the world still derives about 80% of its energy from fossil fuels, like oil, gas and coal, which release the carbon dioxide that’s warmed the climate to the current temperatures of this scalding summer.”

“The WMO’s chief, Petteri Taalas, said this week, ‘In the future these kinds of heatwaves are going to be normal.’

“The most alarming word in his forecast might be: ‘normal.’

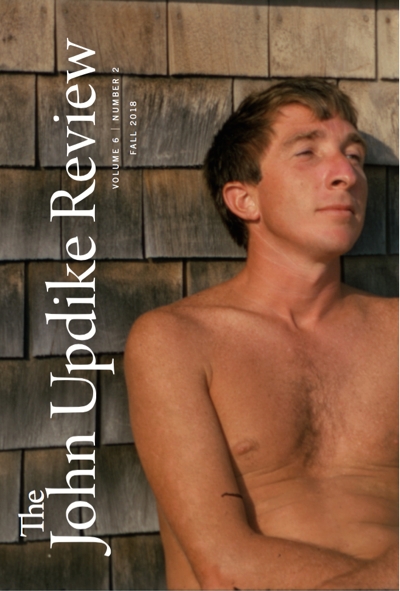

“I’m of a generation that thought of summer as a sunny time for children. I think of long days spent outdoors without worry, playing games or just meandering. John Updike wrote in his poem, ‘June’:

The sun is rich

And gladly pays

In golden hours,

Silver days,

And long green weeks

That never end.

School’s out. The time

Is ours to spend.

There’s Little League,

Hopscotch, the creek,

And, after supper,

Hide-and-seek

The live-long light

Is like a dream…

“But now that bright, ‘live-long light’ of which Updike wrote, might look menacing in a summer like this.

“In blistering weeks such as we see this year, and may for years to come, you wonder if our failures to care for the planet given to us will make our children look forward to summer, or dread another season of heat.”