Category Archives: First Person Singular

More debate on Updike’s stature

It’s funny how one appraisal leads to another, or a conversation . . . or a debate.

William Deresiewicz’s essay-review of Updike for The New Republic has already inspired a favorable response from National Review, that other side of the aisle publication. That’s encouraging, because these days Updike appears to be one of the few subjects that a liberal or conservative can agree upon.

Now Peter J. Leithart (First Things) weighs in with “Painter of Surfaces,” posted online on September 10, 2014, which oddly enough has nothing much to do with Updike’s painterly style.

“No one has to defend Updike’s skill as a writer,” Leithart writes, “and he was surely a success, as Deresiewicz’s rapid-fire summary indicates. . . . Updike’s reputation suffers more because he was, in Deresiewicz’s words, ‘an unembarrassed, unreconstructed middle-American. . . . Updike’s life and work are testaments to the idea that mid-American values, beliefs, and sensibilities are adequate to address and interpret modern experience.’ That cannot be forgiven.

“Nor can Updike’s theological conviction. . . . But he, like the non-judgmental God of his novels, stays on the surface. Updike will be remembered as a chronicler of his times, but Deresiewicz doesn’t convince me that his novels have the depth to be of enduring importance.”

National Review is Looking at Updike, Again

“It’s not cool to like the writing of John Updike,” National Review‘s Michael Potemra declares in “Looking at Updike, Again.” “But it’s the right thing to do.”

Wasn’t that what actor Wilford Brimley told us about eating oatmeal?

Potemra explains that the “anti-feminist rap against Updike deserves, in our current cultural plight, a little more attention. The locus classicus of this opinion was the famous phrase of David Foster Wallace, who quoted a female friend’s gibe that Updike was ‘a penis with a thesaurus.’ Now, David Foster Wallace has basically been canonized as a secular saint, and to be dismissed by him in this fashion amounts to having the phrase NOT. COOL. branded on your forehead.”

Potemra was apparently inspired to reconsider Updike after reading a New Republic book review of Adam Begley’s Updike by William Deresiewicz, whom he quotes:

“Updike—and Mailer, and Roth, and the other men (and women) of their generation—were situated at a complicated juncture in the history of sexuality. They came of age before the revolution, but not so long before that they couldn’t try to join it. Sexual freedom descended on them not as a birthright, but as a miracle. Of course they went a little wild. When the Pill came out in 1960, the oldest member of the baby boom was fourteen. Updike was 28. If he spent a lot of time thinking about sex, it’s not a big surprise. Updike, like his contemporaries, was also too early for feminism. That may not be conducive to the most progressive attitudes . . . but it also means that Updike stood between the old and new Victorianisms.”

Potemra adds, “Deresiewicz is pointing to something important: Updike, as a man of his generation, did not view ideologizing about men and women to be his basic calling in life. It was sufficient for him to watch men and women, to notice, and to record his observations in some of the best prose ever produced by an American writer.”

A.O. Scott writes on the Death of Adulthood

Film critic A.O. Scott dips one toe in familiar waters and the other in American literature to discuss what he perceives as “The Death of Adulthood in American Culture,” which was published on September 11, 2014.

Both Philip Roth and John Updike are mentioned—Roth, more so than Updike.

“While [Leslie] Fiedler was sitting at his desk in Missoula, Mont., writing his monomaniacal tome [on Love and Death in the American Novel], a youthful rebellion was asserting itself in every corner of the culture. The bad boys of rock ‘n’ roll and the pouting screen rebels played by James Dean and Marlon Brando proved Fiedler’s point even as he was making it. So did Holden Caulfield, Dean Moriarty, Augie March and Rabbit Angstrom—a new crop of semi-antiheroes in flight from convention, propriety, authority and what Huck would call the whole ‘sivilized’ world.

“From there it is but a quick ride on the Pineapple Express to Apatow. The Updikean and Rothian heroes of the 1960s and 1970s chafed against the demands of marriage, career and bureaucratic conformity and played the games of seduction and abandonment, of adultery and divorce, for high existential stakes, only to return a generation later as the protagonists of bro comedies. We devolve from Lenny Bruce to Adam Sandler, from Catch-22 to The Hangover, from Goodbye, Columbus to The Forty-Year-Old Virgin.

Writer quotes Updike on L.E. Sissman

In a Wall Street Journal piece titled “Mortality as Muse; L.E. Sissman deserves to be revived,” a Sightings columnist tells about a now-obscure ad man turned poet whose premature death from cancer elicited remarks from John Updike.

“So why read him now? John Updike put it well in his New Yorker obituary: ‘One said goodbye to Ed wondering each time if it would be the last time. It marks the quality of the man that this shadow became something pleasant: an extra resonance in the parting smile, a warmth in the handshake. He helped us all, in his work and in his courage, to bear our own mortality.’ He still does, as do Ms. Adams and Mr. Myers, whose willingness to write with equal honesty should inspire all of those who grapple with the common dilemma, whether its coming be imminent or merely prospective.”

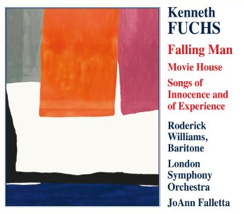

Composer credits Updike for inspiration

Naxos, “The World’s Leading Classical Music Group,” published an article last year that might have slipped everyone’s notice, but since lately the Updike detractors have been rattling the picket fence with their sticks, it seemed a good time to post “Kenneth Fuchs and JoAnn Falletta record fourth disc with the London Symphony Orchestra” (September 23, 2013). The recording includes Falling Man (based on a fragment from Don DeLillo’s post-9/11 novel), Movie House (“seven poems by John Updike for baritone voice and chamber ensemble”) and Songs of Innocence and of Experience (inspired by four of William Blake’s poems).

Naxos, “The World’s Leading Classical Music Group,” published an article last year that might have slipped everyone’s notice, but since lately the Updike detractors have been rattling the picket fence with their sticks, it seemed a good time to post “Kenneth Fuchs and JoAnn Falletta record fourth disc with the London Symphony Orchestra” (September 23, 2013). The recording includes Falling Man (based on a fragment from Don DeLillo’s post-9/11 novel), Movie House (“seven poems by John Updike for baritone voice and chamber ensemble”) and Songs of Innocence and of Experience (inspired by four of William Blake’s poems).

Fuchs writes, “When I read John Updike’s new novel Rabbit Is Rich in 1982, I knew I had come upon a writer whose words would inspire me for a very long time. Updike’s observations about American life and the objects and desires of the American sensibility spoke directly to me. I fell under the spell of his poetry and found many poems that I thought would be right for musical setting. Movie House is a cycle of seven poems set for baritone voice and chamber ensemble (flute, oboe, clarinet, string trio, and harp) from Updike’s second volume of poetry, Telephone Poles, published in 1963. The poems include ‘Telephone Poles,’ ‘Maples in a Spruce Forest,’ ‘Seagulls,’ ‘The Short Days,’ ‘Movie House,’ ‘Modigliani’s Death Mask,’ and ‘Summer: West Side.’

“When performed together, the collection lasts about 31 minutes. I was attracted to these poems because of their optimistic evocations of life during the 1950s, the decade in which I was born. Read some fifty years later, the poems have a nostalgic quality that seems both ironic and poignant. I chose the title of the poem ‘Movie House’ as the title of the entire work. The first poem, ‘Telephone Poles,’ introduces the phrase ‘our eyes’ and the idea of observation, which runs throughout the cycle. The music accompanying that phrase (an ascending major second followed by an ascending major sixth) forms the musical motive from which the melodic and harmonic structure of the entire work evolves. Like the images on a movie screen, the musical setting of each poem is meant to provide the listener with an aural, visual, and emotional perspective from which to observe the world.”

Amazon is currently selling the CD for $11.47.

Guardian writer weighs in on Updike’s rubbish

The Guardian Books Blog recently posted an item on “Raiding John Updike’s Rubbish—a trashy pursuit.” As the headline implies, the writer thinks that “a reread of the Rabbit books might be a better way of sneaking a peak into the mind of their author, rather than rummaging around in what he threw out.”

“As for me, I didn’t spend long on Moran’s blog—it felt sleazy, to be looking through such intimate pieces of a man’s life—and Updike was a man who shared much with the world, through his fiction.

“There is one picture, though, which Moran found and which the Atlantic published, which gives me reason to pause, briefly, in this decision. It’s of Updike, on a basketball court, involved and lean, and it’s so completely reminiscent of the start of Rabbit, Run that I can’t stop gazing at it.”

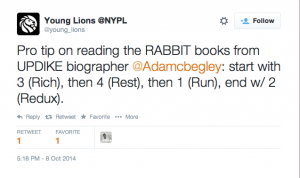

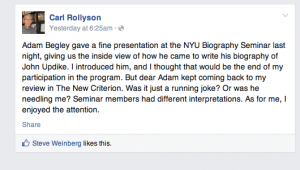

Begley interview inspires prose poem

Janet Cormier of Oddball Magazine was inspired to write a prose poem about a writer and fan because of “a radio interview about John Updike by one of his biographers and a first time caller fan.”

Here’s the link to “Bamboozled No More! Writer and Fan”

Updike scores a 1 on this 200 Best American Novels list

Writing for PBS, Victoria Fleischer on September 11 posted an article titled, “Have you read the 200 ‘best American novels’?”

She reported that a single individual “embarked on an experiment” and “committed to reading only American novels and decided to compile a list of the 100 best that were published between 1770 and 1985.”

The architect of this plan was, well, an architect from Massachusetts named David Handlin.

Not surprisingly, Updike’s Rabbit, Run made the list. But it does raise an eyebrow that it’s the ONLY Updike book included. The Pulitzer Prize winner Rabbit Is Rich didn’t make his list, nor did Updike’s own favorite book, the National Book Award-winning The Centaur.

Handlin’s picks have caused a stir, with Sandra Gilbert, a distinguished professor of English emerita at the University of California, questioning the criteria for “novel” and “American.” She wrote her own list in response, and one of the things she did was to remove Updike—though she was quoted in the PBS article as saying “I’m not at all inclined to demand deletions, but prefer instead to suggest additions that would make this mini-narrative of our literature (for a narrative it is) more representative of the culture we’ve inherited.”

Is Updike’s star now dim, as one reviewer thinks?

In “Controlled Rapture” (September 15, 2014), which is not available through open-access online yet, William Deresiewicz reviews Begley’s Updike for The New Republic. Though he has some very nice things to say about Updike, he begins, curiously, with the (some might think flawed) assumption that Updike’s literary star is currently dim, tarnished, or falling. Ignoring the large volume of major newspapers and critics who continue to assess Updike as one of the great writers of his century, Deresiewicz instead trots out Harold Bloom’s “oft-quoted remark that Updike was ‘a minor novelist with a major style'”—a great sound-byte in an era that feeds off of them—and David Foster Wallace’s decades-old indictment of Updike and the white male literary establishment in an essay many dismissed as the howl of a young buck trying to take on the alpha male(s) during rutting season.

“Only time will tell if Begley’s book becomes a final send-off or the start of its subject’s rehabilitation,” Deresiewicz continues. “Neither, I suspect. Updike’s prospects, in the near term, do not look any brighter than they did around the time that Wallace dropped his bomb in 1997 (or than those of Mailer and Roth, the other ‘phallocrats’ he named in his indictment). Our cultural politics are still pretty much where they were at the time: shackled to our identity politics. But Updike strikes me as the kind of writer who is going to be rediscovered, and who is going to keep being rediscovered. The time will come—in thirty or fifty or a hundred years—when the values of our own effulgent age will seem as odious as those of the 1950s (or for that matter, of the 1850s) do to us today. No one then will care how Updike did or didn’t vote. They will turn to him—readers will, and writers, I think, especially will—for what is permanently valid in his work: the virtuosity of his technique, his ability to craft a sentence, a scene, a story, to calibrate tones and modulate effects; the penetration of his eye, his gift for seeing things and seeing into minds; his brave, honest, unembarrassed frankness; and the sheer aesthetic pleasure of his prose.”

The word count for this review—close to six thousand words—justifies not only the writer’s predictions for Updike’s literary legacy, but also underscores the fact that, at least according to The New Republic, he’s a major figure now.

Perhaps the most telling sentence in Deresiewicz’s review is “No one then will care how Updike did or didn’t vote.” Those who would deny Updike his seat in the American literary pantheon are still bothered by his hawkish stance during the Vietnam years, and still annoyed that a man who steadfastly and consistently voted Democratic wouldn’t be more political in his fiction. But while Bellow and Roth were writing about professors and a segment of society that many would consider more elite, Updike gave us that quintessential fictional representation of the American middle class: Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom. That in itself is as political a statement as the artists who first departed from unwritten academy rules and painted everyday scenes with the scale and scope normally reserved for great battles and historical events. And it’s no coincidence that Updike’s painterly hero was Vermeer.

Reputations ebb and flow, and those fortunate enough to become part of the canon in their literary afterlives must be complex enough, important enough, and representative enough to withstand future attempts to oust them. Updike’s fiction, as Deresiewicz suggests, has the potential to last because when all is said and written about, Updike was and will always remain for readers a very talented writer who had plenty to say about science, religion, relationships, and trying to live life as a middle-class American in a century that was moving technologically forward at such a rapid pace that life itself could become a challenge.

“Does the Rabbit cycle finally cohere?” Deresiewicz asks, rhetorically. “Does it amount to the ‘epic’ that its author dreamed of writing, Begley tells us, in his youth? Maybe not,” he concludes, though there are many who would disagree. “Maybe, like Rabbit, it loses momentum and shape. Maybe Updike never did write that one big book, that single indelible masterpiece. Maybe his corpus is less than the sum of its parts. But what parts.”